“The English and French languages are the official languages of Canada for all purposes of the Parliament and Government of Canada, and possess and enjoy equality of status and equal rights and privileges as to their use in all the institutions of the Parliament and Government of Canada.”

—Excerpt from the Official Languages Act, 1969

At the time of Canada’s Confederation in 1867, French language rights were strictly defined: the use of French was permitted in parliamentary debates in Québec City and Ottawa, federal laws were to be published in both languages, and trials could be held in either language in Quebec and federal courts. It was little indeed, given the considerable proportion of Francophone Canadians.

Things evolved slowly — very slowly. For example, postage stamps became bilingual only in 1927, banknotes in 1936, and simultaneous translation wasn’t introduced in the House of Commons until 1959.

At the beginning of the 1960s, tempers began to flare. Whether in terms of education, access to public services and civil service positions, or for symbolic recognition, many Francophones felt like second-class citizens in their own country. In Quebec, the Quiet Revolution reflected the discontent of French Canadians (we are not yet speaking of “Quebecers”) in relation to their economic, cultural and political situation.

“Maîtres chez nous !” [Masters in our own house!] became the electoral slogan of the Quebec Liberal Party in 1962. Many were also attracted by the option of independence. Anglo-Quebecers were unsettled by this new sense of pride: would their existing rights be threatened?

Outside Quebec, other Francophone communities were also asserting themselves. In New Brunswick, for example, Acadians were encouraged by the accession of one of their own: Louis Robichaud, who became Premier of the province in 1960.

In Ottawa, and among Anglophone Canadians, “What does Quebec want?” was a frequent refrain. The country was undergoing a period of redefinition: although many maintained their vision of a country that was essentially British by tradition, language and ethnicity, others dreamed of something more modern, more independent, more flexible, which would better embrace linguistic realities and diverse identities.

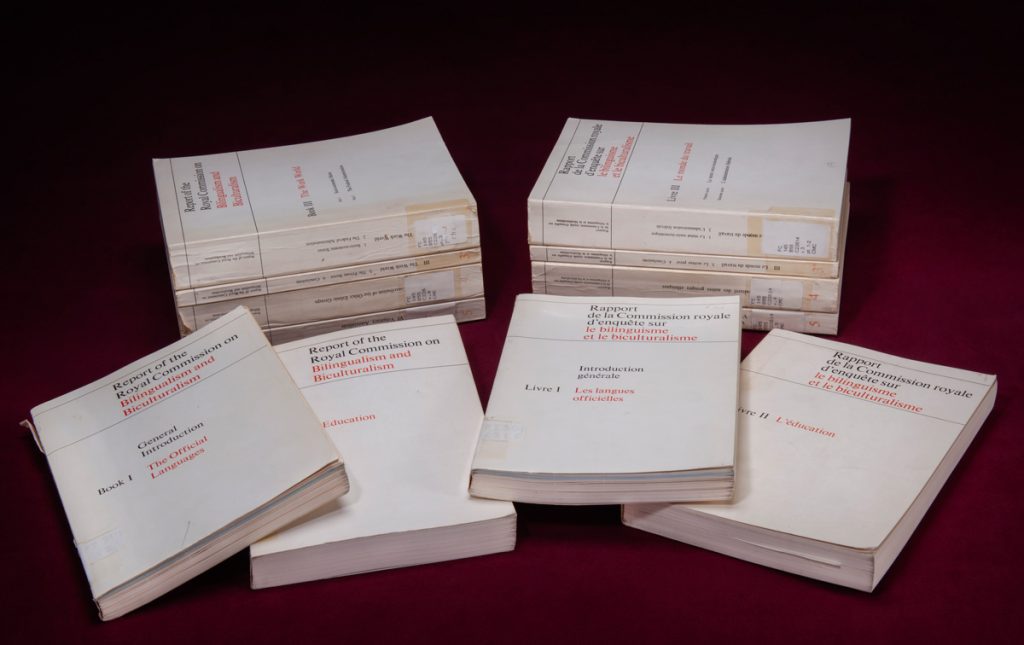

Laurendeau-Dunton Commission’s report in English and French. Canadian Museum of History FC 145 B55 C226 and FC 145 B55 C22614, IMG2019-0230-0002-Dm

On January 26, 1962, André Laurendeau, Editor-in-Chief of the prestigious daily newspaper Le Devoir, called for a major commission of inquiry on bilingualism and biculturalism to take stock of the situation, once and for all. His words were taken seriously.

Lester B. Pearson’s new government announced the creation of just such a commission in July 1963. Its co-chairs were André Laurendeau and Davidson Dunton, President of Carleton University and former Chairman of the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. They would be assisted by eight commissioners and an extensive research team.

For 93 months, the Commission criss-crossed the country, receiving 400 statements and holding hundreds of hearings — including public meetings and even cocktail parties — trying to determine the thoughts and opinions of some 20 million Canadians. The Commission’s members discussed, disagreed, reconciled and submitted a six-volume report calling for more balance between the country’s Anglophones and Francophones.

The federal government had already made some important gestures. One of the more notable was the civil service Policy on Bilingualism, presented by Prime Minister Pearson in April 1966 and affirming in principle equality of access for Anglophones and Francophones.

But it was the Official Languages Act, from its coming into effect on September 7, 1969, that cemented and gave new momentum to this linguistic restructuring. From that point on, civil servants could work in the language of their choice, wherever numbers justified. More to the point, Canadians from sea to sea would have access to most government services in the language of their choice.

A new chapter in Canadian history had begun.

Part 2 – The Official Languages Act: The Early Years (1969–1977)

Dr. Xavier Gélinas is Curator, Political History at the Canadian Museum of History.