The October Crisis shook Montréal, Quebec and Canada in 1970. In Montréal on October 5, a Front de libération du Québec (FLQ) cell kidnapped U.K. trade attaché James Richard Cross. The FLQ, founded in 1963, used violence to advocate for Quebec independence and radical socialism. On October 10, a separate cell kidnapped Quebec’s Minister of Labour and Manpower, Pierre Laporte. Never before had the country experienced anything like it.

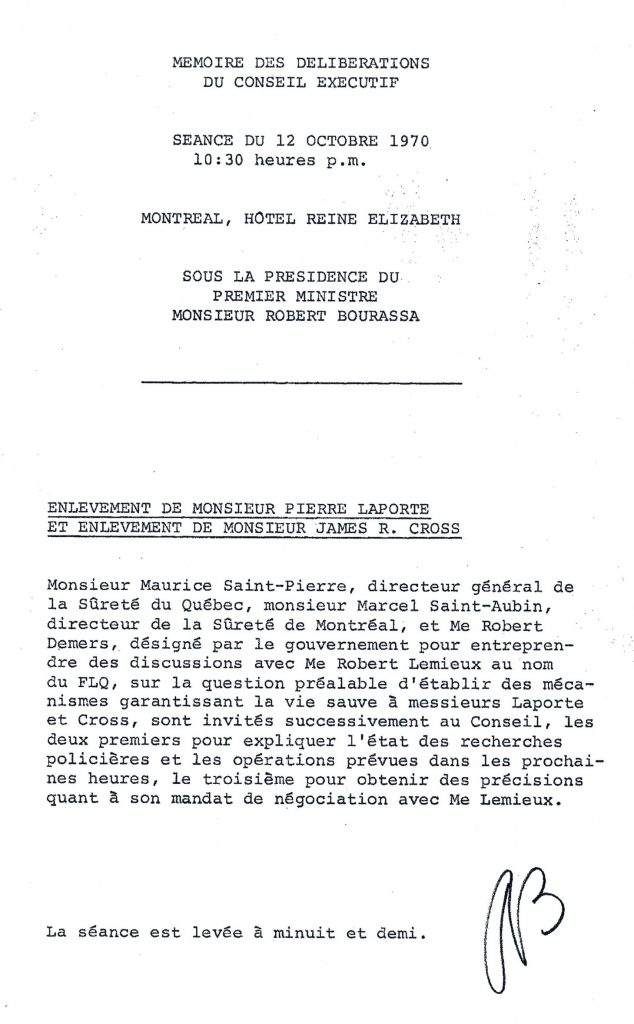

Was this the beginning of an insurrection? The Quebec government, led by Premier Robert Bourassa, was shaken by the kidnapping of Cross, and traumatized by that of Laporte. How could both lives be saved? Give in to the kidnappers? Police efforts intensified. At the same time, Quebec tasked lawyer Robert Demers to negotiate with the FLQ.

Who is Robert Demers?

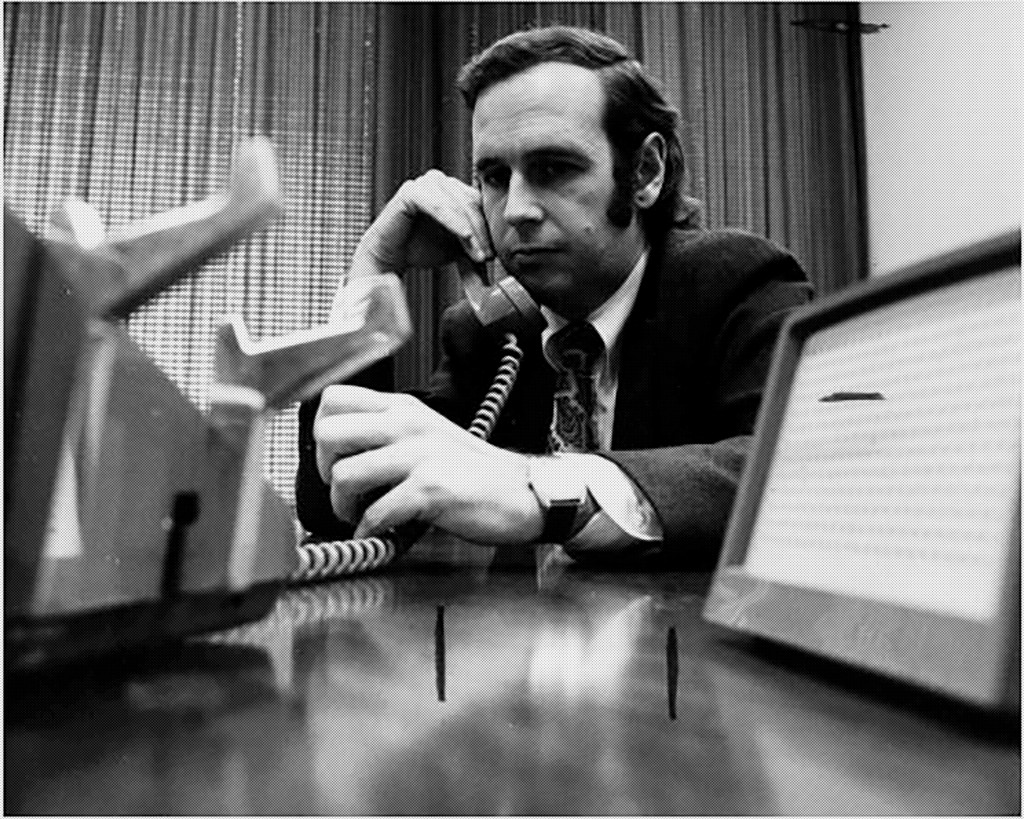

Robert Demers in 1973. Photo: Antoine Désilets. La Presse Archives.

At first glance, nothing predisposed the 33-year-old lawyer to play a key role in the Crisis. Nothing . . . except Demers’s composure and Premier Bourassa’s absolute confidence in him. Born in 1937, and a McGill graduate, Demers was a friend of Bourassa’s. They belonged to the same generation and both were lawyers. An activist within the Quebec Liberal Party since the late 1950s, in 1970 Demers headed up the party’s legal commission.

Professionally, following stints on the Montréal Stock Exchange and with the Ministry of Education, Demers joined the Montréal law firm Desjardins, Ducharme and Choquette in 1966, specializing in finance law. His career took a dramatic turn in the fall of 1970. After the October Crisis, he presided over the Quebec Securities Commission and, after 1976, the Montréal Stock Exchange. In the 1980s, he began working for various investment companies, while remaining periodically involved with the Liberal Party.

James Cross and Pierre Laporte

Front page of The Montreal Star, featuring negotiator Robert Demers, October 13, 1970. Gift of Robert Demers, Canadian Museum of History, Archives, 2018-H0008.6.004.

Demers was unfortunately unsuccessful in his negotiations for the release of Laporte. The Minister was found dead in the trunk of a car on October 17, the day after the War Measures Act was invoked by Canadian Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau. Laporte’s death outraged the country.

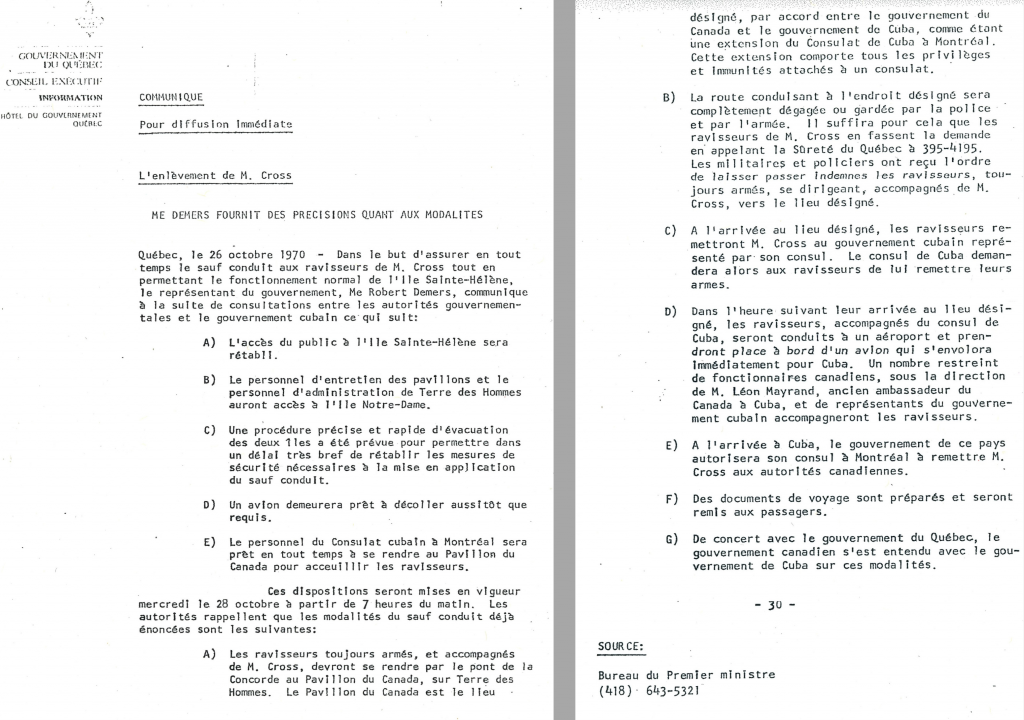

Cross would have a less dire fate. He owed his rescue to tireless police searches and the careful balancing act of Demers, who dealt with authorities in Québec City and Ottawa, the government of Cuba, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, the Montréal police, the Sûreté du Québec, and a lawyer representing the FLQ. A deal was struck: Cross’s captors would receive safe passage to Havana in exchange for the diplomat’s release. The deal was finalized on December 3, 1970. Demers’s mandate came to an end.

First-hand Accounts

Smith & Wesson Model 10 .38-calibre revolver, provided to lawyer Robert Demers by the Sûreté du Québec for his protection during negotiations with the FLQ. Gift of Robert Demers, Canadian Museum of History, 2015.88.1. Photo: IMG2018-0102-0119-Dm.

As a curator, I had the pleasure of meeting Demers at his home in Montréal. Quick-witted and young at heart, the lawyer was keen to share his memories, rarely discussed, and to entrust the Museum with tangible evidence of “his” October Crisis. He donated a Smith & Wesson revolver that had been recommended to him by the Sûreté du Québec for his protection in October 1970, as well as another, a Walther, to be used by his wife Liliane Densky. A soldier was stationed in front of the Demers home, another paced in the backyard, and a third was posted inside, but nothing was being left to chance. It was a time of great fear and violence.

Artifacts From a National Crisis

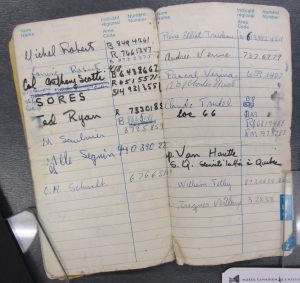

Notebook used by lawyer Robert Demers in October 1970. This page features a sampling of people related to the Crisis: Pierre Elliott Trudeau, Prime Minister of Canada; Lucien Saulnier, Chair of the Montreal Executive Committee; provincial minister William Tetley; Claude Trudel, Principal Secretary to Quebec Premier Robert Bourassa; Colonel Anthony Scotti, Army veteran and chief of Premier Robert Bourassa’s security; and Inspector Van Houtte of the Sûreté du Québec. Gift of Robert Demers, Canadian Museum of History, Archives, 2018-H0008.1. Photo: 2018_H0008_1_BT_AvT_12_2020.

Demers also donated a collection of text-based and audiovisual documents to the Museum’s Archives. The collection contains a number of rare items, including an address book Demers used intensively during the Crisis to record contact information for decision-makers he might have needed to reach at any time of the day or night. Also included are memoirs of the proceedings of the Quebec cabinet — which met at a hectic pace throughout the fall of 1970 — as well as press releases issued by Premier Bourassa’s office, excerpts from the Journal des débats of the Assemblée nationale du Québec, and a wealth of press clippings, bringing to life the media frenzy of that season.

A portion of Demers’s memorabilia was featured at the Museum from December 18, 2021 to September 5, 2022 as part of the exhibition Lost Liberties – The War Measures Act. The entire donation has been carefully preserved, and will provide future researchers with important first-hand material from a key player in a national crisis.

Press release from the office of Quebec Premier Robert Bourassa, October 26, 1970. It discusses the taxing negotiations conducted by lawyer Robert Demers with the Cuban government, authorities in Ottawa and Québec City, and the police. Gift of Robert Demers, Canadian Museum of History, Archives, 2018-H0008.2.024 and 2018-H0008.2.025.

Memorandum of the Proceedings of the Executive Council, Government of Quebec, October 12, 1970. This nightly cabinet meeting, held under heavy security in Montréal, included Robert Demers and the heads of the provincial and municipal police forces, following up on the abductions of James Cross and Pierre Laporte. Gift of Robert Demers, Canadian Museum of History, Archives, 2018-H0008.5.003.

For more information:

- Dr. Xavier Gélinas, “The October Crisis: A Personal Experience,” Canadian Museum of History blog, October 5, 2017.

- Dr. Xavier Gélinas, “October 1970: Multiple Perspectives On A Drama,” Canadian Museum of History blog, October 15, 2020.

- Learn more about the suspension of civil liberties in Canada during the First World War, the Second World War, and the 1970 October Crisis by visiting the special exhibition Lost Liberties – The War Measures Act, on view at the Canadian Museum of History until September 5, 2022, or by purchasing the exhibition’s souvenir catalogue.

Xavier Gélinas

Dr. Xavier Gélinas has been Curator of Political History at the Canadian Museum of History since 2002. His work involves enriching and documenting the Museum’s collections of artifacts and documents, while also enhancing public knowledge of Canada’s political history.

Dr. Gélinas is particularly interested in the political and intellectual history of Quebec and Canada in the 20th century.