Politician Allan MacEachen would have turned 100 years old in 2021. Although he had a number of nicknames over the course of his career, “Celtic Sphinx” perhaps best sums up two of the most striking features of his personality: his legendary discretion, and his visceral attachment to his Scottish roots. As a member of Parliament for 27 years (winning no fewer than 10 elections), and a senator for 12, he left his mark not only on his beloved Cape Breton, but on the political and social landscape of this country.

Signature of Allan MacEachen in 1965. Gift of Miss Hilda Wilson, Ottawa, Ont. Canadian Museum of History, 978.197.8

A Proud Son of Cape Breton

Born in 1921 in the small Cape Breton town of Inverness, Allan MacEachen was the son of a coal miner. Life was tough in this part of the Maritimes. MacEachen learned about social issues, not so much from books, but from his own family (the MacEachen couple lost three children at an early age), and from his environment.

During his studies at St. Francis Xavier University, he was influenced by Father Moses Coady and his Antigonish Movement. This school of Catholic social thought aimed to imbue people with a spirit of solidarity by promoting co-operation, unionism and adult education.

MacEachen remained a churchgoer all his life. He kept his faith private, but his religious values inspired his journey. In later life, he attested with a little smile,

“Moral values, though often unstated, enter into the complex collection of considerations that enter into legislative policy. In my legislative career (probably because I am filled with Liberal arrogance!), I thought at times I was ‘building the kingdom’ by supporting legislation with considerable moral values, Christian values.”

In his memoirs, future colleague Barney Danson referred to MacEachen as “the laird of Cape Breton and its banker of first resort,” and described his commitment as follows: “I must say that the Treasury was always at risk when he had a project that benefited Nova Scotia; certainly all opposition was demolished if the beneficiary was Cape Breton Island.”

As much as MacEachen sought to transform the fortunes of his community, he remained committed to the traditions of Cape Breton and his ancestral homeland. Often wearing his clan kilt, he was fluent in Gaelic, and a connoisseur of single-malt whiskey.

Scholarships made it possible for him to continue his studies at the University of Toronto and the University of Chicago, and later at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. MacEachen became a professor of Economics at his alma mater, St. Francis Xavier University, but was drawn to practical action, as he confirmed after his retirement: “Keeping bread on the table, in the widest interpretation of that expression, was the principal reason I left a university teaching post to enter politics.”

A candidate for the Liberal Party in the riding of Inverness-Richmond, he was elected to the House of Commons in 1953, during the term of Prime Minister Louis St. Laurent, and was re-elected in 1957. Defeated in 1958, he remained at the heart of political life as an advisor to Leader of the Opposition Lester B. Pearson. With Pearson’s almost paternal affection, MacEachen helped to modernize the Liberal program and move it in a progressive direction, reflecting the emerging 1960s.

A Minister in the Pearson Cabinet

Returning to Parliament in 1962, and becoming a minister the following year, MacEachen was able to deploy his energy and reformist ways. Heading up the Department of Labour, he introduced the Canada Labour Code, which consolidated and modernized disparate laws related to federally regulated industries, such as banking and transportation. The Code contained the first federal minimum wage, set at $1.25 an hour ― different times, different customs!

In 1966, at the helm of the Department of National Health, he spearheaded what many consider to be a jewel of Canadian identity: the Medical Care Act. This legislation allowed for free medical consultations outside of hospitals, through cost-sharing with the provinces. The Minister had to fight hard for this reform, about which he cared so deeply — even within the Liberal caucus. It was in this same spirit of social solidarity that MacEachen created the Guaranteed Income Supplement for less affluent seniors, which remains a pillar of the Canadian pension system.

It was to the sound of bagpipes, of course, that he entered the Ottawa Civic Centre in 1968, when he ran for leadership of the Liberal Party after Pearson resigned. He was, however, defeated. The new leader, Pierre Elliott Trudeau, nevertheless found in him an outstanding lieutenant.

Certificate given by Allan MacEachen, Minister of Labour, to a retiring employee, March 18, 1965. Gift of the Miss Hilda Wilson, Ottawa, Ontario, Canadian Museum of History, 978.197.8

A Parliamentary Ace

During the Trudeau years, MacEachen was best known as a formidable, and feared, master of parliamentary procedure. The Prime Minister had complete confidence in him, and made MacEachen his righthand man, both figuratively and literally: the two men shared the same desk in the Commons, and MacEachen sat on his right in Cabinet.

Trudeau appreciated MacEachen’s loyalty, his mastery of the political game, and his discretion, which contrasted with the petulance and verbosity of so many parliamentarians. Historians Jack Granatstein and Robert Bothwell refer to MacEachen’s “maddeningly inscrutable” character, as he knew how to conceal his cards. The bachelor’s private life was a closely-guarded secret. He could not be relied upon to leak inside information to the press, and even his views remained mysterious to his colleagues — until, with calculated impact, he would take a strong stand that would galvanize the caucus and Cabinet.

Allan MacEachen demonstrated his skills as House Leader, a demanding position he held three times for a total of seven years ― a record in Canada. Being a leader means knowing everything, anticipating everything. From 1972 to 1974, MacEachen quite literally kept the then-minority Trudeau government alive, through his skillful dealings with the New Democratic Party.

He was given the position of Secretary of State for External Affairs in 1974, a dream portfolio for a man who wanted to promote issues such as North-South dialogue and the search for some sort of “third way” during the Cold War era. His happiness lasted only two years. In 1976, beset by worries, Prime Minister Trudeau recalled MacEachen to his side as House Leader. He was appointed Deputy Prime Minister in 1977, the first person to hold the position.

Seven former Canadian foreign ministers are seen together in this rare photograph taken around 1996. Left to right: Mitchell Sharp, Allan MacEachen, Flora MacDonald, Joe Clark, Barbara McDougall, Lloyd Axworthy and Perrin Beatty. Canadian Museum of History, Mitchell Sharp Collection, 2005.32.64 (photo 7036-2111-8137-IMG2008-0060-0025-Dm)

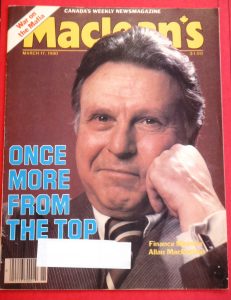

Appointed Minister of Finance, MacEachen made the front page of Maclean’s on March 17, 1980.

Shortly after Joe Clark led the Progressive Conservative Party to a minority government in May 1979, Trudeau announced his resignation. MacEachen became Leader of the Opposition. He demonstrated his parliamentary wizardry once again with a threefold feat: in December that year, he orchestrated the movement that overthrew the Clark government; he then convinced Pierre Elliott Trudeau to come out of retirement and return to lead the Liberals; and, finally, he played a key role in the February 1980 campaign that returned the Liberals to power and a majority government.

Allan MacEachen inherited the Finance portfolio in recognition of his achievements. It was a prestigious, but poisoned gift. The country was in recession. Interest rates, inflation and unemployment were soaring. And the deficit was at an all-time high. It was a perfect storm. MacEachen’s social reformism did not mesh well with these harsh economic conditions. It was with relief that he returned to his former position at External Affairs in 1982.

The Last Battle

Allan MacEachen’s final hour of fame came as a Senator, when he was appointed to the Upper House in 1984. Now in opposition, after Brian Mulroney and the Progressive Conservative Party had taken power, he fought tooth-and-nail against the proposed Canada-United States Free-Trade Agreement. When Mulroney was re-elected in 1988, MacEachen was forced to give up the fight, although he went on the offensive again in response to the Goods and Services Tax. For months, with a Liberal majority in the Senate, MacEachen held the government at bay. Prevented from proceeding, the Mulroney government resorted to a special clause in the Constitution, never used in Canada before. Appointing eight new Senators in one fell swoop, the government finally got the controversial bill passed.

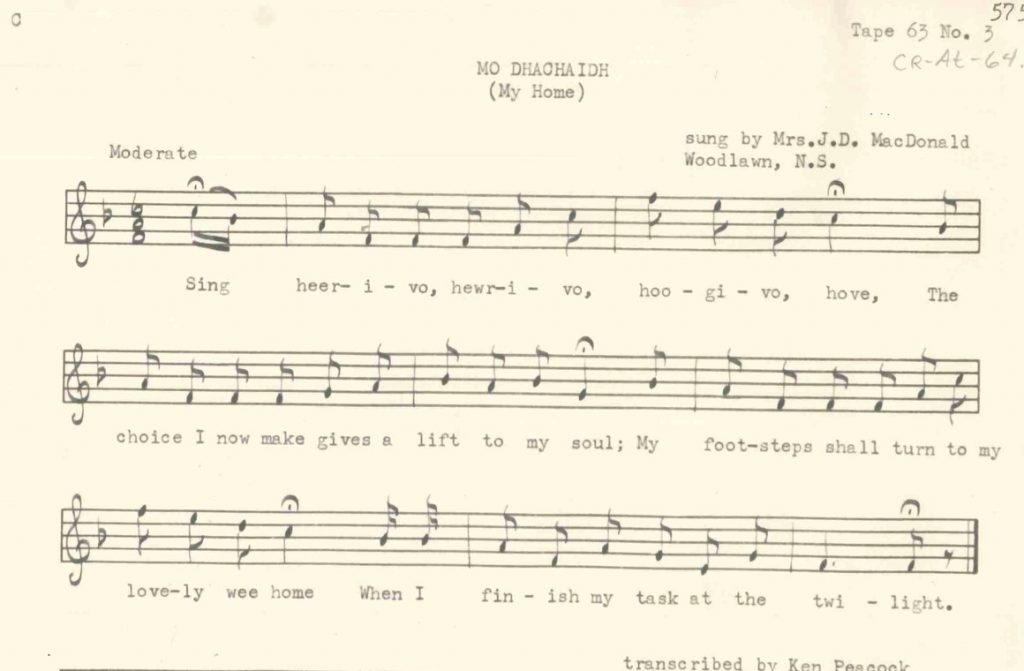

MacEachen left the Senate in 1996. He passed away at the age of 96 on September 12, 2017, in Antigonish, and was buried in his hometown of Inverness. At his request, the old Scottish song Mo Dhachidh (My Home) was sung at his funeral:

“The choice I now make gives a lift to my soul;

My footsteps shall turn to my lovely wee home

When I finish my task at the twilight.”

Gaelic score and English translation (1951) of the Scottish song Mo Dhachidh (My Home), performed at the funeral of Allan MacEachen. Canadian Museum of History Archives, Helen Creighton Collection, DOCSFOLK B120/17