In the early morning of September 26, 1968 — 50 years ago this month — Canadians were stunned to learn that Daniel Johnson had passed away during the night. The Premier of Quebec, who had suffered from heart disease, was scheduled that very day to inaugurate the Manic-5 hydro-electric power station. It was the largest multiple-arch-and-buttress dam in the world, and perhaps the most striking symbol of a period of renewal and pride in Quebec known as the Quiet Revolution.

The previous day, the beaming Premier had visited the site, chatting with workers and engineers, and exchanging a three-way handshake with his predecessor Jean Lesage, and with René Lévesque, the former provincial minister responsible for the nationalization of electricity, and a future premier himself. The resulting photograph was an iconic image of contemporary Quebec.

Daniel Johnson did not, however, begin his career as a politician with a modernizing bent. Born in 1915 in Danville, in Quebec’s Eastern Townships, the young lawyer was first elected to the constituency of Bagot in 1946, under the banner of the Union nationale, the political party of Maurice Duplessis. In 1958, he was named Minister of Hydraulic Resources. In 1960, the Union nationale lost the election; its founder Duplessis died a year later, and the party underwent a turbulent time.

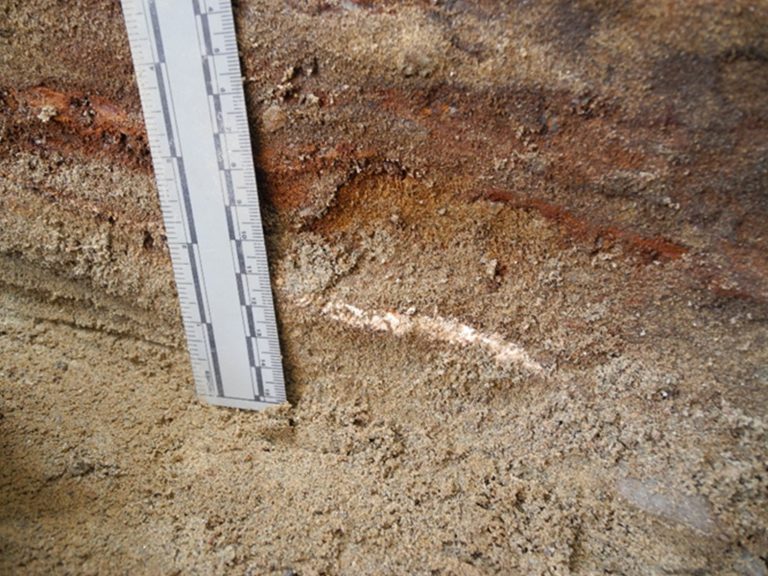

Promotional ruler, around 1958. Canadian Museum of History

Johnson became leader of the Union nationale in 1961, and to many represented “the old guard.” Commentators viewed him as populist and old-fashioned, and political cartoonists depicted him as an unscrupulous cowboy, calling him “Danny Boy” — an allusion to his Irish origins. Johnson, however, had used his years in opposition to renew the platform and organization of the Union nationale, and to recruit promising new faces. To everyone’s surprise, thanks to solid support in rural areas and a splitting of the vote between a number of small independent parties, he defeated Jean Lesage’s Liberals in the 1966 Quebec election.

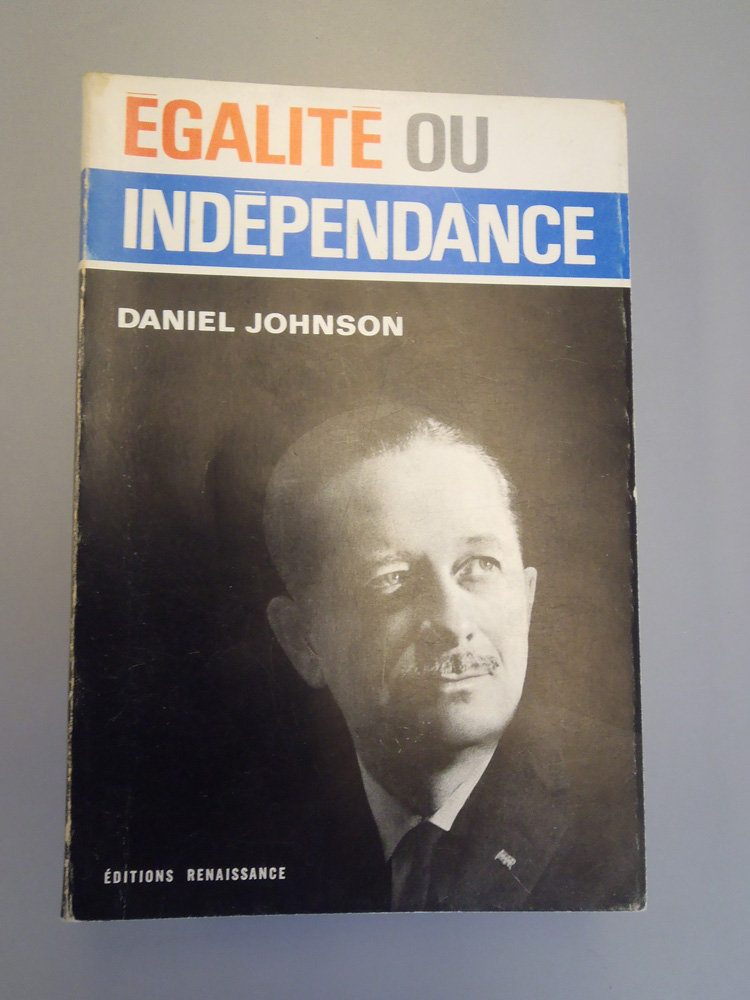

It was then that the once-cautious political leader showed his true colours: those of a premier with a sense of statehood, who wanted not only to maintain but accelerate Quebec’s growing self-affirmation and sense of identity. Within the broader realm of relations with the federal government in Ottawa, he issued an ultimatum that was both resounding and ambiguous: “Equality or Independence.” Johnson flirted with the Quebec autonomy and independence movements, without committing himself irrevocably to either cause.

Égalité ou indépendance, published in 1965. Canadian Museum of History

He formed an extraordinary bond with French President Charles de Gaulle and accompanied the general during his epic tour of Quebec in July 1967. It was also under Johnson’s leadership that CEGEPs — an educational cornerstone bridging high school and university — were born. His government was also responsible for founding the Ministry of International Relations, which expanded Quebec’s place on the world stage; and Radio-Québec, which would later become Télé-Québec.

The loss of Daniel Johnson marks 1968, in both Quebec and the rest of Canada, as a year of reconfigured political roles and realities. French Canada’s most influential intellectual, André Laurendeau, passed away in June of that year. The former editor-in-chief of the daily newspaper Le Devoir, and Joint Chair of the Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism, was among those who, like Johnson, sought to resolve the “Quebec Question.”

Canadian Prime Minister Lester B. Pearson, an advocate of “cooperative federalism,” had retired in April. From that point on, constitutional issues would become more polarized. On June 25, Pierre Elliott Trudeau was elected by Canadians to a majority federal government, with an undertaking to end all special treatment for Quebec. Less than four months later, on October 11, the Parti Québécois was founded. Led by René Lévesque, the new party would pursue the road to sovereignty, without any ambiguity whatsoever. A new cycle had begun.