Jean Chrétien served as Canada’s Prime Minister for 10 years, from 1993 to 2003. That alone would have been enough to earn him an enduring place in Canadian history. However, for Chrétien himself, the role of Prime Minister was simply the crowning moment in a long and eventful career.

Born on January 11, 1934, in Shawinigan, in the central Quebec region of La Mauricie, Joseph Jacques Jean Chrétien would one day leave his hometown, but would always proudly remain, “the little guy from Shawinigan.” He was the eighteenth of 19 children born to Marie Boisvert and machinist Wellie Chrétien. Young Jean came from a modest background and, despite all of his later successes, would retain his working-class accent, and his blunt and feisty attitude.

He was still in school when he fell under the spell of Aline Chaîné, whom he married a short time later. She became his “Rock of Gibraltar,” as he often enjoyed saying — his gentle and thoughtful counterpart — and he made no major decisions without her approval. Their love story would end only with Aline’s death in 2020, following 63 years of marriage.

The restless Jean went from school to school, ending up at the Séminaire de Trois-Rivières, then at Université Laval, where he earned a law degree. Political upheaval was in the air. Swimming against the tide of a Quebec on the verge of the Quiet Revolution, Chrétien remained fiercely pro-Canada. Although a newly minted lawyer without a fortune behind him, he tossed his hat into the ring in Saint-Maurice during the 1963 federal election, and was elected a Member of Parliament for the Liberal Party of Canada. This marked the beginning of an enduring relationship between Jean Chrétien and his constituents, who elected him 12 times in as many campaigns.

Jean Chrétien was driven by a number of deeply held convictions: his unwavering support for federalism, his francophone pride, and his interest in the needs of ordinary people. He kept his distance from the elites who, in turn, often looked down their noses at him. But he was not dogmatic — it was pragmatism that characterized his 40 years of political life, along with a desire for action.

First Steps Towards Ottawa

For a more or less unilingual 29-year-old francophone from a remote region, landing in Ottawa in 1963 had its challenges. Chrétien made his mark based on the strength of his tireless work. He also had his eye on a place at the table: a seat in Cabinet. Prime Minister Lester B. Pearson liked this spirited MP who was willing to plunge into economic files under the watchful eye of Finance Minister Mitchell Sharp. Chrétien’s reward came in 1967, when he was given the modest portfolio of Minister of State for Finance.

Canada’s Cabinet, July 1, 1967. Queen Elizabeth II and Prime Minister Lester B. Pearson are in the middle of the front row. Newly named Minister Jean Chrétien is standing at the far right in the back row. Photo: John Evans. Gift of the Estate of Mitchell Sharp. Canadian Museum of History, Photographic Archives, 2007-H0032_12, IRN 5821689.

Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development (1968–1974)

Jean Chrétien quickly learned the ropes, becoming a full-blown minister in January 1968 — this time, Minister of National Revenue. When Pierre Elliott Trudeau took over as leader of the country in Summer 1968, he transferred Chrétien to Indian Affairs and Northern Development, an appointment that astonished Chrétien. By his own admission, he knew nothing about either Indigenous affairs or northern development. It is one of the ironies of Canadian history that Chrétien came to love the department, recalling with emotion:

I stayed six years, one month, three days, and two hours, and I loved every minute of it. […] This time was probably the most productive of my career in terms of the number of decisions made and initiatives taken. An excitement seemed to seize the entire department.

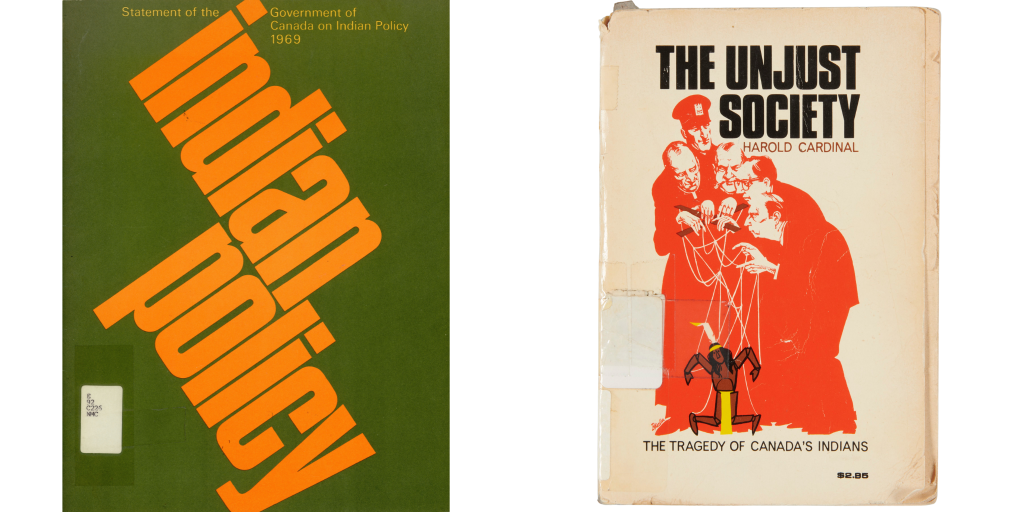

One of his first major decisions, however, fell spectacularly flat. He submitted the White Paper (also known as the Statement of the Government of Canada on Indian Policy, 1969) with the well-meaning but poorly thought-out intention of erasing the subordinate status of Indigenous peoples in Canada — but, at the same time, all the rights they had gained. The gloves were now off, as distilled in the essay The Unjust Society: The Tragedy of Canada’s Indians by Cree intellectual Harold Cardinal. Clearly, Minister Chrétien and the Prime Minister had misjudged the situation, and had not heeded the voices of Canada’s Indigenous peoples. The White Paper was withdrawn, and Chrétien learned, file by file, and community by community, how to earn the respect of First Peoples.

(L) Statement of the Government of Canada on Indian Policy (the White Paper), 1969. Canadian Museum of History, Library, E 92 C226, IMG2023-0366-0006. (R) Book by Harold Cardinal: The Unjust Society: The Tragedy of Canada’s Indians, 1969. Canadian Museum of History, Library, E 78 C2 C372 1969, IMG2021-0090-0001.

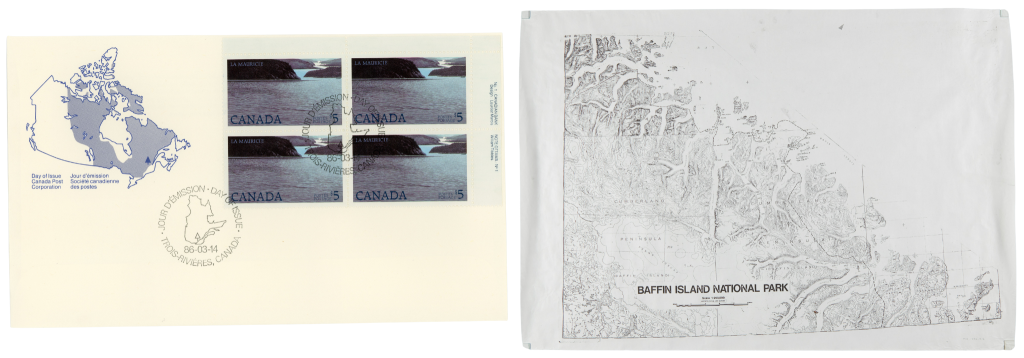

He had more success with another departmental brief: national parks. A lover of Canada’s natural environment, Jean Chrétien created 10 parks during his term, doubling the number of protected acres. One of them was especially close to his heart: the national park in La Mauricie — the first to be created in Quebec and partially located, chance often being a fine thing, in his constituency. Another park — Auyuittuq National Park, in Nunavut — was born, quite simply, during a conversation with his dear Aline, as they looked out the window of a plane. Chrétien remembered the circumstances surrounding the creation of this massive national park:

Once I was flying over Pangnirtung on Baffin Island to Broughton Island, and we passed low over the huge, spectacular fjords there — walls of rock topped with magnificent ice caps and plunging thousands of feet into the ocean. I was so excited that I said to my wife, “Aline, I will make these a national park for you.” When I got back to the office, I asked for a map, and with a pen I circled off 5,100 square kilometres.

(L) First Day Cover marking the inauguration of La Mauricie National Park, 1986. Transfer from Canada Post. Canadian Museum of History, Scott 1084, IRN 259106. (R) Archaeological survey map for the future Auyuittuq National Park, by Peter Schledermann, 1973. Canadian Museum of History, Archaeological Archives, MS 1287_V. 2_a, IRN 3355762.

The Constitution

Jean Chrétien was sad to leave his position at Indian Affairs and Northern Development following the 1974 federal election; however, his leader Trudeau needed him elsewhere. Chrétien became the government’s jack-of-all-trades. One might say that, the stormier the seas, the more likely that the job would be given to this rough sailor. Chrétien accordingly spent several years as President of the Treasury Board, Minister of Energy, Mines and Resources, and Minister of Finance — the first francophone to hold this portfolio since Confederation, and another confirmation of the “French Power” that Pierre Trudeau was bringing to Ottawa. Throughout his career, Chrétien occupied no fewer than 12 Cabinet positions.

His most demanding yet rewarding mandate came during his time as Justice Minister. The country had experienced years of identity-related turmoil. Quebec held a referendum on sovereignty in 1980; the federalist option won out. Prime Minister Trudeau sought to repatriate the Canadian Constitution by attaching a Charter of Rights. At the beginning, the only provincial premiers to support the initiative were Ontario’s Bill Davis and New Brunswick’s Richard Hatfield. The mission was clearly in jeopardy.

Drawing upon both his tenacity and willingness to compromise, Jean Chrétien overcame the reluctance of almost all the other premiers, finalizing an agreement on the evening of November 4, 1981. These efforts led to the historic signature of a new Constitution by Queen Elizabeth — a moment of intense pride for Jean Chrétien. There was, however, a dark cloud on the horizon: the Quebec government, led by René Lévesque’s Parti Québécois, refused to add its signature. Bitterness was alive and well among sovereigntists, as well as among Quebec nationalists. This would come back to haunt Chrétien nearly 15 years later.

![(L) Sheet of paper titled Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, with a dedication(R) Brocuhe with the title Minute, Ottawa! [Just a Minute, Ottawa!], put out by the Quebec government](https://www.historymuseum.ca/blog/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/JeanChretien-7-8-1024x512.png)

(L) Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, with the dedication, “To my friend, Mitchell.” Mitchell Sharp had been Jean Chrétien’s mentor since Chrétien’s arrival on Parliament Hill in 1963. Gift of the Estate of Mitchell Sharp. Canadian Museum of History, Archives, 2007-H0032.1.001, IRN 3543512. (R) Minute, Ottawa! [Just a Minute, Ottawa!], a brochure put out by the Quebec government, protesting repatriation of the Constitution, 1981. Gift of the Honourable Serge Joyal. Canadian Museum of History, Library, FC 633 C6 M56 1981, IMG2017-0455-0001.

Party Leader: First and Second Attempts (1984 and 1990)

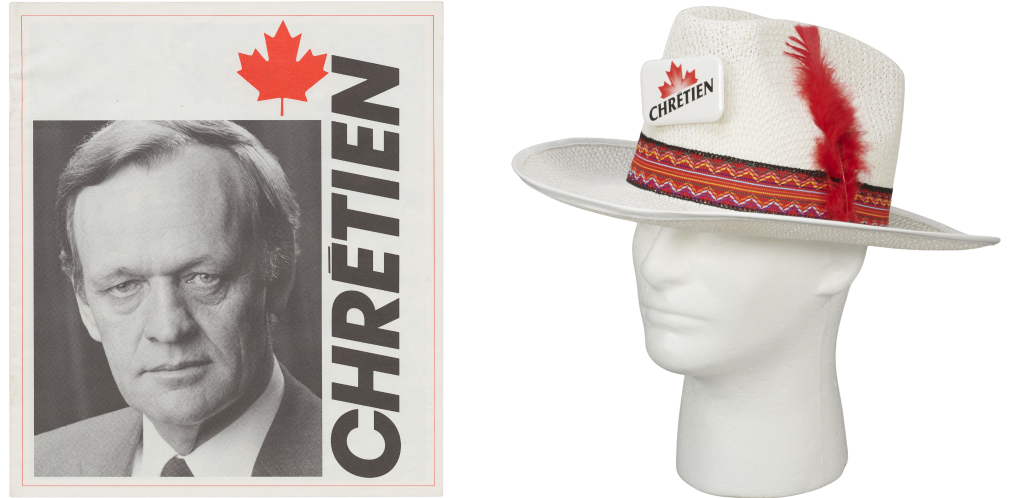

Jean Chrétien quit politics for the first time in 1986. Two years earlier, in 1984, following the retirement of Pierre Elliott Trudeau, John Turner had won the race for leadership of the Liberal Party. A climate of conflict had set in between Chrétien and his new leader. However, in 1988, Turner’s second successive defeat at the hands of Brian Mulroney’s Progressive Conservative Party reshuffled the deck. John Turner gave up leadership of the Liberals, and his position was now up for grabs. Chrétien tried his luck once again. The prize had eluded him in 1984; would the second time be the charm? Playing upon his extensive experience, Jean Chrétien became head of his party at the leadership conference in Calgary in 1990, defeating, among others, his brilliant rival Paul Martin.

(L) Flyer supporting Jean Chrétien for leadership of the Liberal Party of Canada, 1984. Gift of Grant Harper. Canadian Museum of History, Archives, 2023-H0003_60_001, IRN 3287691. (R) Hat worn by supporters of Jean Chrétien at the Liberal Party of Canada conference, Calgary, 1990. Gift of the Honourable André Ouellet. Canadian Museum of History, 2018.117.1, IMG2021-0008-001.

Prime Minister (1993–2003)

Photograph dedicated by Prime Minister Chrétien to Brigadier-General Clayton Beattie and his wife, Kay, around 1995. Photo: Jean-Marc Carisse. Gift of Brigadier-General Beattie. Canadian War Museum, Archives, CWM20070182-155, IRN 3184932.

Jean Chrétien was ready for the federal election in October 1993. He knew that his direct style, considered endearing at times and abrasive at others, was not everyone’s cup of tea. But isn’t that always the way in politics? He was clever enough, however, to rely on his team, and on a solid program known as the “Red Book.”

The political context of the time worked in his favour as well. After nine years in power, the Progressive Conservative Party, then led by Kim Campbell, was suffering from general discontent. In the West, the Reform Party was gaining in popularity, eating into mainstream Conservative support. In Quebec, a new sovereigntist party, the Bloc Québécois, also had the wind in its sails and was undermining Conservative support. Empowered by divisions within the electorate, the Liberal Party won a clear majority in the House of Commons — including 98 of the 99 seats in Ontario, its new stronghold.

Jean Chrétien became the twentieth prime minister of Canada, and the first party leader since the Second World War to win, in succession, two more majorities, in 1997 and 2000.

A Mentor: Mitchell Sharp

During his time as Prime Minister, Jean Chrétien retained the services of a man he considered his mentor: Mitchell Sharp (1911–2004). An economist and senior civil servant who had been a federal minister under both Pearson and Trudeau, Sharp had an almost paternal affection for the young Chrétien when the latter, newly arrived on Parliament Hill, sought to penetrate the mysteries of government finances.

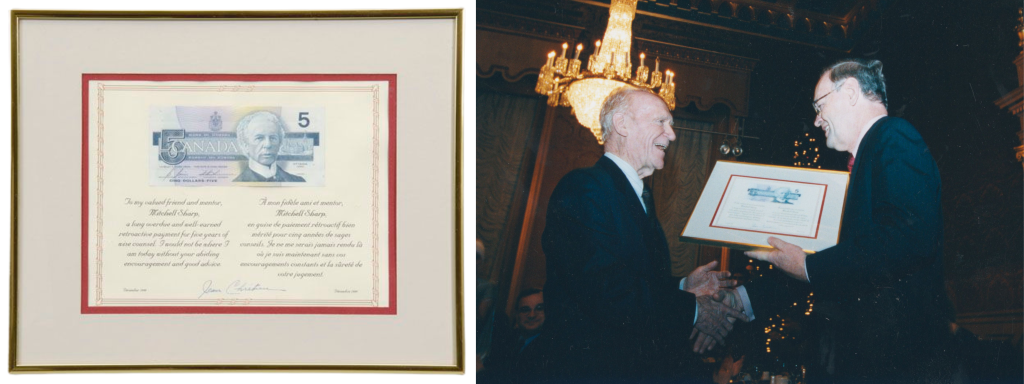

Already in his eighties in 1993, Sharp agreed to advise his former protégé. He had only one condition: that he be given a nominal annual salary of one dollar. In 1994, Sharp did indeed receive his dollar; however, over the course of the ensuing years, both employer and employee neglected their business arrangement — so much so that the Prime Minister had to pay five dollars all at once in 1999, in a small ceremony that was both funny and moving. Mr. Sharp’s widow, Jeanne d’Arc Labrecque Sharp, offered the Museum this proof of back pay — an amount that was never deposited.

(L) Framed five-dollar bill, with this dedication by Jean Chrétien: “To my valued friend and mentor, Mitchell Sharp, a long overdue and well-earned retroactive payment for five years of wise counsel. I would not be where I am today without your abiding encouragement and good advice.” — December 10, 1999. Gift of the Estate of Mitchell Sharp. Canadian Museum of History, 2005.32.67, IMG2008-0060-0085.

Referendum, Take Two (1995)

Jean Chrétien grappled with many different briefs during his 10 years in power. Neither success nor controversy was lacking — plenty of ink could be spilled on both. Of particular note among his government’s achievements was the spectacular — if painful — rejigging of public finances to eliminate the federal deficit. Guided by Finance Minister Paul Martin, and with Chrétien’s wholehearted support, this budget exercise placed Canada on a solid financial footing. It was also under Jean Chrétien that the territory of Nunavut was born in 1999, giving Inuit control over the future of an area in which they were the majority population.

At the international level, it was under Chrétien that the North American Free Trade Agreement came into effect in 1994, and that Canada ratified the 1997 Kyoto Protocol on climate change. He also demonstrated clear support for NATO by participating in the intervention in Afghanistan following the attacks of September 11, 2001. At the same time, however, he asserted Canada’s sovereignty by declining to follow the United States into the war in Iraq, which began in 2003.

As for so many other Canadian prime ministers, national unity preoccupied Jean Chrétien. The Meech Lake Accord, which would have given Quebec the status of “distinct society,” was rejected in 1990. A large proportion of the Quebec population was outraged by this, and sought sovereignty. A referendum was announced by the Parti Québécois government for October 30, 1995.

For Chrétien, this second fight, following the one in 1980, didn’t just embody a crucial political choice, but would mean rifts within nearly every family. More than ever, he believed in Canada, and sought to sway his fellow Quebecers. In his Shawinigan riding, several weeks before the vote, he issued an appeal:

Jean Chrétien’s appeal bore fruit, but by a very slim margin. The federalist “No” option won a narrow majority of 50.58% at the provincial level. In his own constituency, the “Yes” vote prevailed at 54.9%. Jean Chrétien was relieved, but it was a hard knock politically, and even personally. Years later, in his farewell speech as Prime Minister in 2003, he said of that time:

Let me tell you, it was tough, my friends. It was tough for all of us who stood for Canada. It was very tough for me personally. It hurt me deeply. It hurt my family. To be vilified in my home province — the province I love — just for standing up for Canada. Because I believed so profoundly, as I still believe today, that being part of Canada is best for Quebec. But no matter how lonely it was — we never gave up.

My dear friends, together with all other Canadians, we Quebecers have built a great country: Canada. A country that isn’t perfect, it’s true; a country that must continue to adapt to modern realities, it’s true; a country that can and should improve itself, to be sure; but a country that also continues to be the envy of the entire world. We all have reason to be extremely proud of it.

Her Majesty

Surprisingly, there were strong ties between Jean Chrétien and the British Royal Family, and particularly with the sovereign, Queen Elizabeth II. They first met during Canada’s Centennial Celebrations in 1967. From Commonwealth summits to Canadian tours, to repatriation of the Constitution, the “little guy from Shawinigan” and the Queen enjoyed numerous opportunities to chat — with Her Majesty always speaking in French.

As Prime Minister, Jean Chrétien also met with her at Expo 2000 in Hanover, Germany, as well as during a royal tour in 2002, when the Queen visited our Museum. As a mark of royal consideration, in 2009 Chrétien received the Order of Merit, a coveted decoration bestowed personally by the Queen.

(L) Oversized flag, displayed in the Canada Pavilion at Expo 2000 in Hanover, Germany. At the top, you can see the signatures of Queen Elizabeth II and Jean Chrétien above those of hundreds of visitors. Transfer from the Canadian Embassy in Germany. Canadian Museum of History, 2007.172.1, IMG2011-0348-0002. (R) Visit of Queen Elizabeth II to the Canadian Museum of Civilization, alongside Jean Chrétien, October 13, 2002. Photo: Harry Foster, Canadian Museum of History., Photographic Archives, IMG2008-0497-0013.

Visit of U.S. President Bill Clinton to the Canadian Museum of Civilization, now the Museum of History, February 23, 1995. Left to right: Aline Chrétien, Hillary Rodham Clinton, Bill Clinton, and Jean Chrétien. Photo: Harry Foster. Credits: Canadian Museum of History, Photographic Archives, IMG1995-0039-0003.

An Ally and Friend: Bill Clinton

Of all the political figures with whom Jean Chrétien spent time as Prime Minister, he forged his closest ties with U.S. President Bill Clinton. Shared views united these two realistic and centrist politicians, who were both from humble circumstances and rural regions. In the run-up to the 1995 Quebec referendum, the President — first on an official visit to Ottawa, then in a comment made in Washington, D.C. — went as far as the rules of diplomacy allowed, expressing his support for Canadian unity. “Quebec and Canada owe him a great deal,” Chrétien would later admit.

Our Museums

In the Museum’s Grand Hall, granting of honorary Canadian citizenship to Nelson Mandela, November 19, 2001. Left to right: MP John McCallum, Senator Anne Cools, Nelson Mandela, and Jean Chrétien. Photo: Harry Foster. Canadian Museum of History, Photographic Archives, IMG2008-0420-0017.

Jean Chrétien often visited the Museum of Civilization (now the Museum of History). It was one of his favourite venues, where he chose to welcome heads of state and hold gala dinners. It is worth remembering one of the events that marked not only his life, but also the life of this country: the awarding of honorary Canadian citizenship to Nelson Mandela. The hero of South Africa had recognized Canada for the anti-apartheid stance of former Prime Minister Mulroney, and for the support of Mulroney’s successor, Jean Chrétien, in the fraught transition to a multiracial regime.

The Prime Minister was equally interested in our sister institution, the Canadian War Museum. Although it would be his successor, Paul Martin, who attended the official opening in 2005, it was Chrétien’s government that had made the crucial decision to fund the new building. And it was Jean Chrétien who, in 2002, launched the work with a ground-breaking ceremony on LeBreton Flats.

(L) Ground-breaking ceremony for the new Canadian War Museum, November 2, 2022. Left to right: Jean Chrétien; Victor Rabinovitch, President and CEO of the Canadian Museum of Civilization Corporation; Marcel Beaudry, President of the National Capital Commission; and Joe Geurts, Director General of the Canadian War Museum. Photo: Bill Kent. Canadian War Museum, Archives, CWM2019-0065-0031. (R) Ground-breaking for the new Canadian War Museum, LeBreton Flats, November 5, 2002. Left to right: Victor Rabinovitch, President and CEO of the Canadian Museum of Civilization Corporation; Mac Harb, MP for Ottawa-Centre; Marcel Beaudry, President of the National Capital Commission; Jean Chrétien; Sheila Copps, Minister of Canadian Heritage; and Joe Geurts, Director General of the Canadian War Museum. Photo: Bill Kent. Canadian War Museum, CWM2019-0065-0030.

Jean Chrétien: 50 Years of Standing Up for Canada, booklet for an evening gala in honour of Jean Chrétien for his 80th birthday, Toronto, January 21, 2014. Gift of the Honourable Serge Joyal. Credits: Canadian Museum of History, Library, FC 636 C47 J43 2014, IMG2023-0366-0002.

Time for a Quieter Life

After a little more than 10 years in office as Prime Minister, Jean Chrétien left that position on December 12, 2003. In his retirement, however, he has been anything but idle: after returning to his profession as a lawyer, he remained involved in several public initiatives, and wrote three memoirs. For Chrétien himself, as well as for his former supporters and adversaries, partisan passions have faded with time, allowing for a more serene look back at his exceptional trajectory through Canada’s political story.

Learn more:

- “Portrait of a Prime Minister: Paul Martin” blog post by Xavier Gélinas, January 18, 2024.

- “Bill Davis (1929–2021)” blog post by Xavier Gélinas, August 13, 2021.

- “Allan MacEachen, The ‘Celtic Sphinx’” blog post by Xavier Gélinas, November 30, 2021.

Xavier Gelinas

Dr. Xavier Gélinas has been Curator of Political History at the Canadian Museum of History since 2002. His work involves enriching and documenting the Museum’s collections of artifacts and documents, while also enhancing public knowledge of Canada’s political history.