The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has forced significant adaptation and innovation, while exposing long-standing inequities in Canada and the world. We all may be living through the same pandemic, but we are not all experiencing it in the same way.

The curatorial team at the Canadian Museum of History has been working to document examples of the range of pandemic experiences in Canada, safely and effectively. The Museum has aimed to collect COVID-related objects and other content, both physical and digital. This material reflects the diverse voices and experiences of Canadians and Indigenous peoples affected by various policies — including public advice, guidance from official sources, responses, and protests — as well as the transformation of physical spaces, and the impact of the pandemic on cultural expression.

Some of what the Museum has collected on these themes are literally signs of the times. As Canadians adapted to remote working and education, while reducing their social contacts and navigating ongoing closures, they still found ways to stay connected and to express support in times of crisis. Think, for example, of evenings when people banged on pots and pans to show their support for health care workers, or the ubiquitous rainbows in windows, or signs saying “Ça va bien aller” [“It will be alright”].

Solidarity from Home

Tanya Krupilnicki and Richard McIlroy, along with their children Mischa (7) and Naomi (13), wanted to show their support for health care and other essential workers during the first wave of pandemic lockdowns in Ottawa, which began in March 2020. They decided to make a homemade lawn sign in solidarity. As Krupilnicki put it, “It was a bit of a scary time, as we weren’t yet sure how deadly the virus was. We were so lucky and privileged to not have to leave the house to go to work, and so just wanted those that did need to leave the house to work to know that we appreciated it and also worried for them.”

She also noted that it was an important outlet for her children, as it “helped keep a positive attitude with our kids, and a project to contribute in some small way, so it wasn’t all doom and gloom.” Krupilnicki noted that the sign drew many happy comments from neighbours and other passersby, including one worker who made a detour by the house every day on the way to work.

Richard McIlroy, Mischa McIlroy and Tanya Krupilnicki with their lawn sign, August 18, 2021. Photo: James Trepanier, CMH 2021.93

Workplace Safety

Other signs of the times reflected tension and calls for change. In High River, Alberta, for instance, a Cargill meat-processing plant experienced one of the country’s largest workplace outbreaks of COVID-19, during the first wave of the pandemic. Nearly half of the plant’s 2,000 workers and their families — many of them immigrants or migrant workers — fell ill in the spring of 2020, leading to three deaths.

The union representing the workers — United Food and Commercial Workers, Local 401 — protested working conditions at the plant, as well as a lack of suitable personal protective equipment. The plant was temporarily closed to prevent further spread. However, upon its reopening, union representatives provided returning colleagues with specially branded cloth masks as a form of protest, and as a reminder about the ongoing challenges of workplace safety.

Example of cloth mask distributed by UFCW Local 401 at the Cargill meat-processing facility

in High River, Alberta. CMH 2021.53.1

BLM: Adapting the Call for Social Justice

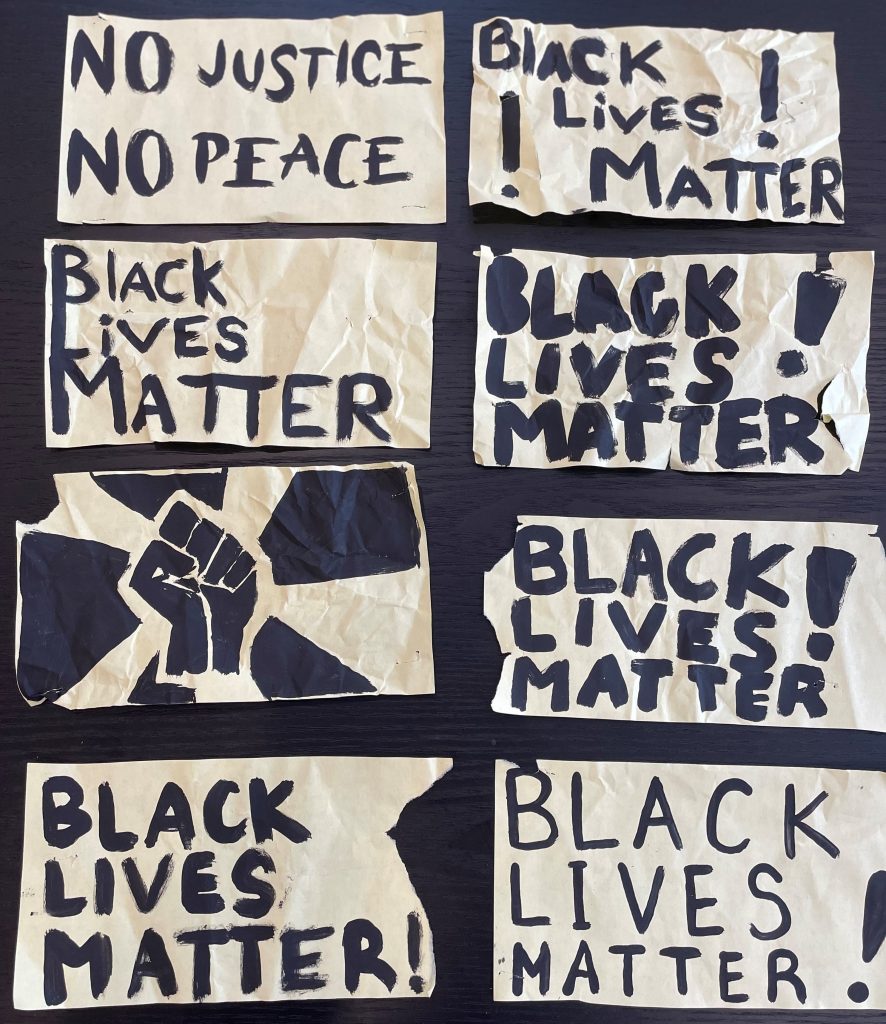

The pandemic also forced broader social movements to adapt to these extraordinary times. New restrictions, health measures, and work defined as “essential” exposed racial and other socio-economic inequities in stark ways. The Black Lives Matter movement in Canada — inspired in part by events in the United States, but also channelling uniquely Canadian perspectives and experiences — held numerous protests across the country in 2020, to call public attention to ongoing racial discrimination in a range of public arenas. Signs and posters like the ones below, left behind on commercial buildings, took on new significance as sustained in-person protests were forced to adapt to public health guidelines.

Black Lives Matter posters from Ottawa, June 2021. CMH 2021.57

No More Lockdowns

Finally, those opposed to public health measures also found ways to express their perspectives. Although libertarian, religious and conservative groups have been vocal in their criticism and opposition to vaccines and other health measures in the past, the public health regulations and restrictions imposed during the COVID-19 pandemic stimulated a response from a small but vocal minority. There was opposition to public curfews, retail closures, size limits on private gatherings (particularly in relation to religious services), travel restrictions, mask requirements, and even the science and efficacy of vaccines and vaccine mandates.

“No More Lockdowns.ca” lawn sign. CMH 2021.36.1

COVID-19 continues to shape Canada and the world, as evidenced in the rise of the Omicron variant and renewed public health measures (and resistance to these) across the country. As noted previously, today’s pandemic echoes past socio-political upheaval over key social and health policies such as vaccine mandates. It has also exposed long-standing socio-economic inequities. In many ways, the signs of these COVID-19 times reflect the ongoing personal, cultural, social, economic and political realities of life in contemporary Canada.