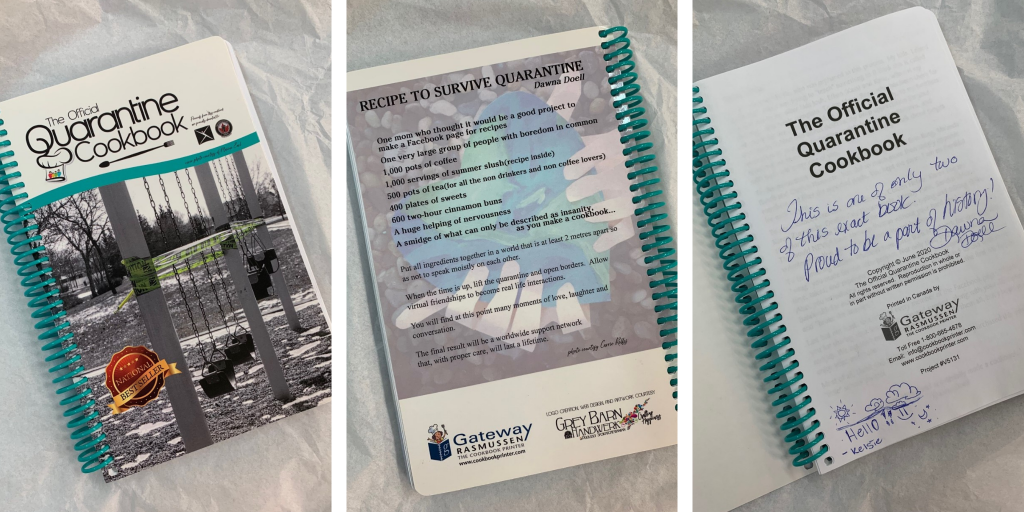

When her children were sent home in March 2020 due to the first COVID-19 lockdown, Saskatchewan mom Dawna Doell decided that their first home-school lesson would be cooking from a recipe. She posted the results of their culinary experiment online, and it went viral. She decided to create a Facebook group for people quarantining at home to share recipes and tips in a friendly and supportive environment. Eventually, the group spawned a cookbook, then several more cookbooks — all bestsellers — with recipes shared by members of their large, but close-knit, Facebook community.

The Official Quarantine Cookbook

Cookbook Community

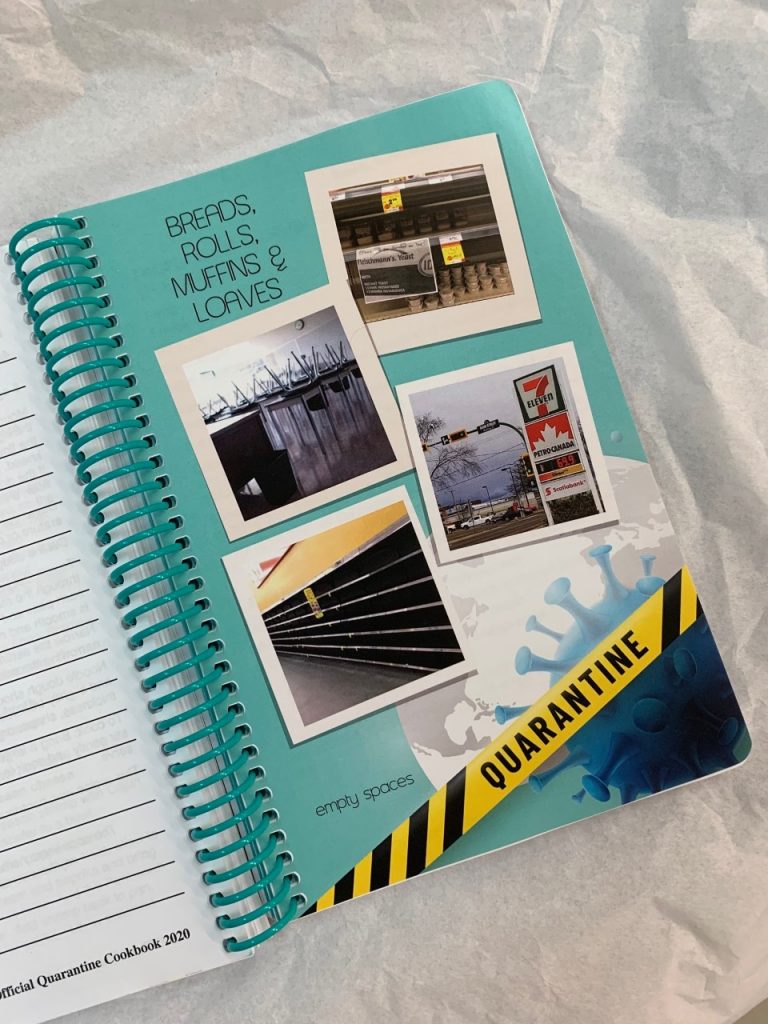

Breads, loaves, muffins and rolls section from The Official Quarantine Cookbook

The cookbooks, filled with recipes perfected and transmitted across the country through digital technology, are not so different from the ways in which pre-internet community cookbooks were shared and developed as snapshots of a specific time, place and people. Instead of a cultural or religious community, however, these cookbooks provide us with still-life shots of pandemic domestic life.

The Canadian Museum of History recently acquired a copy of the first The Official Quarantine Cookbook as part of its plan to collect the experiences of Canadians during the pandemic. For many Canadians, cooking and baking was, and continues to be, an important aspect of pandemic life, and offers us a lens through which to examine and process grief, nostalgia and comfort.

Finding Flour

In the early days of the pandemic, when hoarding toilet paper and hand sanitizer was still commonplace, another few curious items began to fly off the grocery store shelves: flour and yeast. Canadians became bread-making obsessed. On the surface, it seemed simply as though people were finding a new, tasty hobby to indulge in while being forced to stay home 24/7 — but the intense passion devoted to bread-making tells us a little bit about some of the fundamental shifts we underwent beginning in March 2020.

Why the sudden interest in making bread? For many, whether now working from home or forced home due to business closures, the luxury of time to make dough and let it rise before baking was new, as was the need to find home-bound activities to avoid cabin fever. It allowed us to nourish ourselves and our families with simple ingredients at a time when the stability of our supply chains was being questioned.

Homemade baguettes and Montreal-style bagels

Sharing the Fruits of our Labour

Most importantly, bread-making also gave us something we could control, however small. Even when we felt powerless to control so many things around us, we could control our sourdough. In our home, we ran the gamut in our bread-making endeavours, from baguettes to Montreal-style bagels and panini.

When we were finally able to see family again, we brought them warm loaves of carefully braided handmade challah. We ate them over a meal meant to combine and commemorate all the holidays, birthdays, deaths and anniversaries that we had not been able to experience together in lockdown.

We Still Need to Eat

Semiotician Roland Barthes writes that an entire social environment is present in, and signified by, food. Everyday foods often tell unintentional stories, and the recipes, pictures and culinary practices communicated via The Official Quarantine Cookbook and social media show that during the pandemic, sharing foodways became a mediator of sometimes competing and distinct pandemic experiences.

Not everyone has experienced the pandemic in the same ways, and while we each have various levels of pandemic privilege — as well as a diversity of economic, health and social capital — foodways have been a near-universal commonality. Even though our lives were upended in March 2020, we still needed to eat.

Eating Together

Braided handmade challah

Familiar family recipes offered us comfort when grieving lost loved ones. Discovering new recipes added a touch of excitement to pandemic monotony. When feeling comfortable enough to see family and friends again, we did it over food and drink — the importance of commensality and connection taking on new and deepening meanings.

Sometimes a celebration, other times a process to negotiate complicated emotions, cooking can also be an obligation — a response to family needs rather than personal enjoyment. Foodways communicate meaning through ordinary acts and everyday forms.

The Cooking Continues

Object by object, we are developing a collection that offers insight into Canadians’ varied pandemic experiences. Documents such as The Official Quarantine Cookbook show how we communicate through food. The recipes contained within its pages, amassed and collected during difficult days, will continue to be cooked, shared and enjoyed long after the pandemic is over, becoming part of our everyday lives in a new post-COVID world.