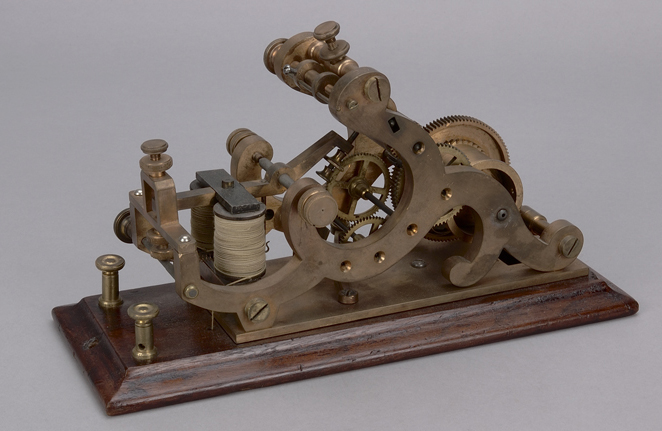

Morse recorder, from the mid-19th century. This device received Morse code signals. Canadian Museum of History, CN-75 a

Long before the invention of cellular telephones, our forebears sent one another instant messages by telegraph. Beginning in 1846, coded messages could be sent in Canada in the Morse alphabet: a code made up of short and long impulses (also known as “dots and dashes”). These messages were transmitted over long distances by cable, using telegraph technology and simple electrical current. Unlike today’s text messages, however, messages sent by telegraph were hard to keep private. Sending a telegram required a qualified operator, who would need to transcribe the messages being sent and decode the messages received. Beginning in the 1850s, the upper middle class had become used to exchanging wishes and news by telegram. Some even enjoyed playing chess this way, sending one another telegrams indicating their last moves. It was the press, however, that would popularize the use of the telegraph, so much so that, towards the end of the 19th century, Canadians in some cities would mob telegraph offices to get the latest news, before publication of the next day’s newspaper.

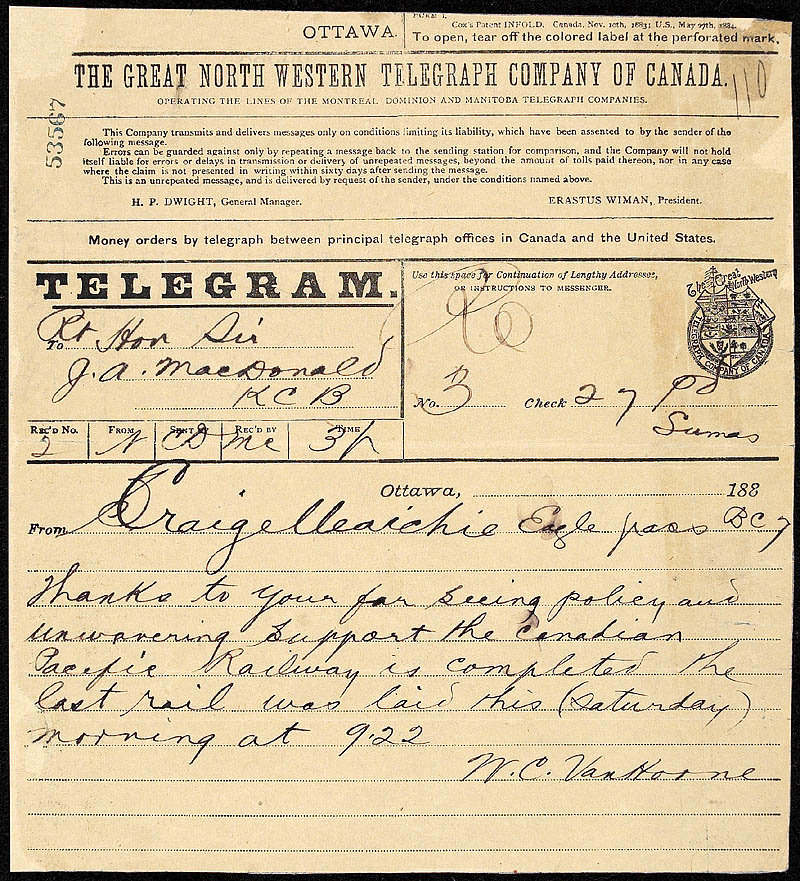

In Canada, telegraph lines were strung along railways, using available electric lines. As a result, the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) company offered telegraph services. Partly thanks to the CPR, a trans-Canada telegraph line was completed in 1886 between Nova Scotia and British Columbia —one year after the completion of the transcontinental railroad, which also stretched from Nova Scotia to British Columbia. It was, in fact, via an official telegram sent on November 7, 1885 by William Cornelius Van Horne, Director General of Canadian Pacific, that Sir John A. Macdonald, then-Prime Minister of Canada, learned that the last spike had been driven into the transcontinental railroad.

Telegram announcing the driving of the last spike of the Canadian Pacific Railway (William Cornelius Van Horne, November 7, 1885 — Ink on paper, Library and Archives Canada, e000009485).

The first attempt at transatlantic telecommunication occurred in 1858, but it was not until 1866 that a functional telegraph cable was permanently laid between Europe and North America. At a time when ships took more than 10 days to cross the Atlantic, telegraph messages now took, in optimal conditions, only a few minutes.

Section of transatlantic telegraph cable made in 1857 by Newall and Co. and used during the first telegraphic transmission between Europe and North America, in 1858. Canadian Museum of History, 2011.38.1

The next advance, at the beginning of the 20th century, was wireless telegraphy, invented by physicist and businessman Guglielmo Marconi (1874–1937). It would prove particularly useful for communication between ships at sea. When the Titanic sank in 1912, the transmission of an SOS message resulted in the rescue of no less than 700 passengers. From then on, seagoing vessels were obliged to use wireless telegraphy.

Battery for a telegraph from the Empress of Ireland. Canadian Museum of History, 2012.21.499

Closer to home, when the Empress of Ireland sank at the mouth of the St. Lawrence River on May 29, 1914, although 1,012 people perished, 465 people would be saved, thanks in part to the use of this new device. The Canadian Museum of History has many such objects in its collection, including a battery used by a telegraph on the Empress of Ireland, bearing witness to that tragedy.

Never underestimate the historical role of the telegraph!