Hockey Canada created a national women’s team in 1990, and the first official Women’s World Hockey Championship was held in Ottawa that same year. Organizers of the tournament initially struggled to sell tickets. As a publicity stunt, the tournament committee decided to have Team Canada wear pink jerseys and white satin hockey pants.

Many female players and organizers were angry. They felt that pink uniforms trivialized the athleticism of the new national women’s team. The controversial decision paid off, however, in publicity and ticket sales. Team Canada won gold at the tournament, and the pink jerseys were retired.

The pink jerseys were not the first time a women’s hockey uniform had been controversial. In 1938, members of the Preston Rivulettes were forbidden to wear their jerseys in the national women’s championships, because the jerseys bore the name of the team’s sponsor: the Preston Springs Hotel. The team had agreed to add “Springs” to their jerseys, in exchange for money to buy new equipment.

The problem was that sponsorship was prohibited by the Dominion Women’s Amateur Hockey Association, sponsor of the tournament. Taking any kind of sponsorship or money was regarded by the public with suspicion, and players were expected to play simply for the love of the game. Members of the Rivulettes certainly loved hockey, but they also needed help to pay for new equipment.

Such financial support was badly needed during the Great Depression. Due to the restriction on sponsorship, in the end Rivulettes players wore the “Springs” jerseys during the regular season, but borrowed other jerseys for the championship tournament. In spite of the controversy, they took home the Lady Bessborough Trophy in 1938: a prize awarded to the best women’s hockey team in Canada during that era.

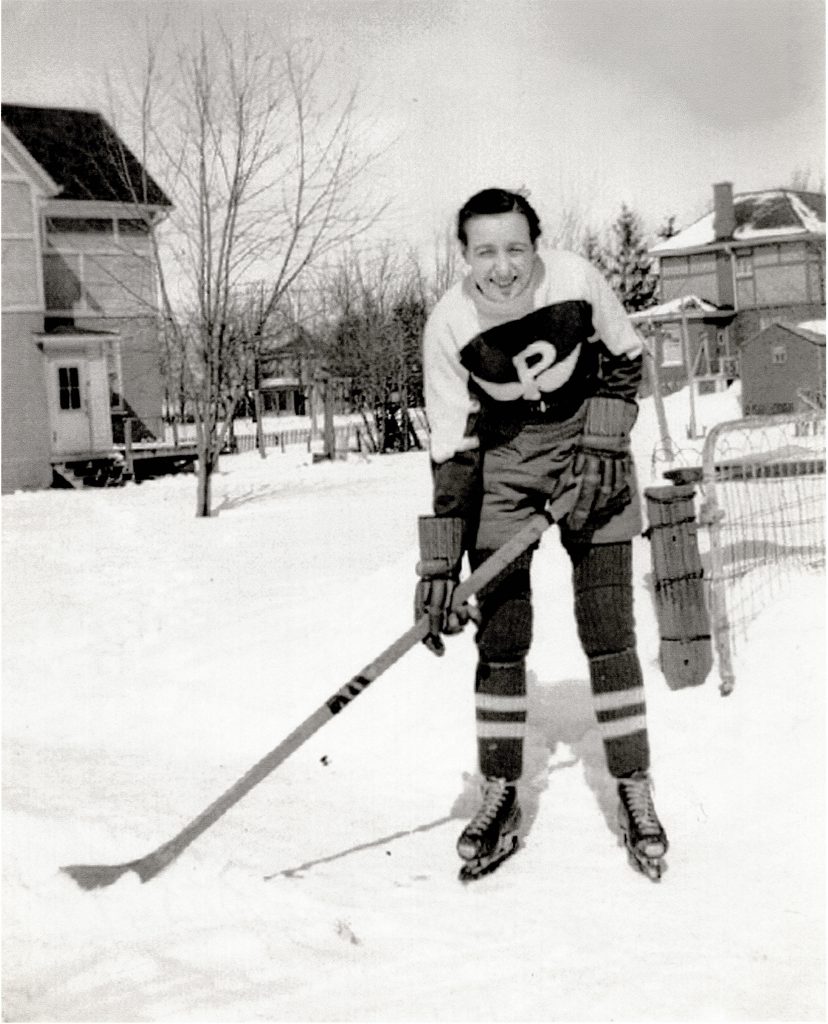

Hockey uniform and skates that belonged to Hilda Ranscombe, star player with the Preston Rivulettes. Canadian Museum of History, IMG 2016 0253 0021-DM

Acquired by the Canadian Museum of History in 2015, this hockey uniform and skates belonged to Hilda Ranscombe, star player with the Rivulettes. These iconic objects will be displayed for the first time in the Hockey exhibition, presented at the Museum from March 10 to October 9, 2017. The acquisition includes a wool jersey and socks, as well as canvas shorts that buckle at the waist.

Ranscombe and friends from her baseball team put the Rivulettes together because they wanted to play a winter sport. Hockey was an obvious choice in their hometown, where there were plenty of outdoor rinks, as well as an indoor arena. The young women were given money from a local Member of Parliament to hire a coach and enter their team in the Ladies Ontario Hockey Association.

Dr. Carly Adams’ Queens of the Ice tells the story of the Rivulettes, who dominated Canadian women’s hockey from 1933 to 1940. They reached the national finals every year and won four championships. Thousands of fans paid to see the Rivulettes and other women’s teams play hockey in the 1930s. Local and national newspapers covered the women’s teams. Victories were publicly celebrated, and players became local celebrities.

The Rivulettes’ play was described as “scrappy” in newspaper reports of the time. Female players did not treat each other delicately — they even exchanged punches — and their aggressive play raised eyebrows. Sometimes reporters criticized the Rivulettes for playing “like men.”

Commentators also described female players as “sweet,” and implied that hockey was too rough on women. But women wanted to play, and they persisted. Most members of the Rivulettes worked in factories during the day and practiced after work and on weekends. Female teams did not get priority ice time, so they had to practice when space was available.

Hilda Ranscombe circa 1933, City of Cambridge Archives, Family of Hilda Ranscombe

Following their 1930s heyday, women’s hockey leagues all but disappeared during the Second World War. Teams were formed during the 1940s and 1950s, but there were few tournaments and no leagues for women again until the 1970s. Since 1990, however, registration in girls and women’s hockey has increased tenfold.

The aggressive play, fan support and overall popularity of teams like the Rivulettes deepen our understanding of women’s hockey history. One thing is certain: hockey is not new to women. Ranscombe’s jersey and skates remind us that hockey is an intrinsic part of Canadian society. Who gets to play, what is controversial and what is acceptable have significantly changed over time, and will continue to evolve.

The story of the Preston Rivulettes is just one of the many fascinating aspects of Canada’s national winter sport explored in Hockey, opening at the Museum of History on March 10.

Who is your favourite female player, and why?