For many generations people from around the world have chosen to make Canada their home. A favourite destination for thousands of Europeans and Americans since the 18th century, Canada became an important destination in the mid-19th century for African-Americans, for whom the name “Canada” was synonymous with freedom.

The Canadian Museum of History has recently acquired the handwritten text of a song expressing a slave’s desire to flee the United States. The song is the work of Joshua McCarter Simpson (1820–1876), an African-American composer and agent on the Underground Railroad. Titled “I’m on My Way to Canada,” the song tells the story of a slave who wants to escape north of the border, despite the difficult climate — our “cold and dreary land.” Simpson composed the song in his home state of Ohio in 1852, and it first appeared as part of a collection in Original Anti-Slavery Songs, a pamphlet published that same year containing several songs promoting the abolitionist cause.

Context of the 1850s

The American Civil War was a few short years away. The rift between the South and the North, between the forces for and against slavery, was deepening. Following the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850, the stream of migrants from slave states to Canada was on the rise. Even in the North, many were leaving for Canada, fearing the efforts of slave catchers who, by virtue of the 1850 Act, had the right to recapture any escaped slave, even if they lived in a free state. Consider, for example, the case of Shadrack Minkins, once a slave in Virginia, who fled to Boston, where he found work as a waiter. Following his surprise arrest on February 15, 1851, and a spectacular escape, Minkins was whisked away to Montréal. The adventure cost the Boston Vigilance Committee $1,400, a major portion of which was defrayed through a public appeal. Little by little, the abolitionist movement gathered momentum — and for good reason.

Depiction of Slave Family, labouring for their master’s benefit, from « Hauling the Whole Week’s Picking”, painting by William Henry Brown, 1842. Historic New Orleans Collection : 1975.93.2. Cotton was the backbone of the plantation economy in the Southern United States during the first half of the 19th century.

The 1850 Act sent shockwaves through the African-American community. The Underground Railroad, a clandestine and illegal system conducting those fleeing slavery in the South to British North America, grew in size. According to historian Larry Gara, the Black community became increasingly involved in the operation of the Underground Railroad. And behind the Railroad, there was an entire movement — a veritable counterculture — fighting for the abolition of slavery. The movement used every means at its disposal. Abolitionist candidates were presented for election. Newspapers were published, including William Garrison’s famous Liberator and Frederick Douglass’ North Star. Scores of flyers, letters and newspapers were sent through the mail, both to promote the cause and to assist slaves in their personal escape plans.

Media, music and the abolitionist movement

The campaign against slavery was highly visible. The impact of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s bestseller, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, is a case in point. Originally serialized in 1851, the narrative was published as a complete novel in March 1852. By October, just a few months later, sales had reached 125,000 copies. A French version was published in Montréal under the title of La Case du Père Tom in 1853. This meant that, as a young man, Wilfrid Laurier was able to read about Uncle Tom in his mother tongue. A play based on the novel was staged in Toronto and elsewhere. Although the novel’s success may have been due largely to its publisher’s brilliant marketing strategy, there is no denying that there was also considerable demand for this type of crusading literature. The mass movement against slavery was taking flight.

Music has always been an integral part of protest. Abolitionist gatherings, held across the United States, featured songs advocating the pursuit of liberty and the suppression of slavery. These songs were sometimes sung by everyone in attendance or by professional and semi-professional choirs, such as the celebrated Hutchinson Family Singers — well known for their hit, “Get off the Track” — who often appeared at these events, and who attracted more than 20,000 people to a rally in Boston. Simpson was by far the most prolific composer of these songs, and his works figured prominently at abolitionist rallies. Song served as a medium of communication and mass persuasion.

Musical strategy in “I’m on my way to Canada”

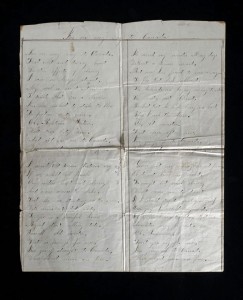

Handwritten lyrics to the song “I’m on my way to Canada,” ©Canadian Museum of History, 2014-H0013, photo Steven Darby, IMG2014-0080-0001-Dm

To take full advantage of the persuasive power of song, Simpson used a strategy common to the wave of evangelical revivals that shook the United States at the beginning of the 19th century, matching his lyrics to the best-known melodies of the day. He thus drew on the music of “blackface” minstrel shows, which were enormously popular across the U.S., and which featured songs performed by white actors with blackened faces. The most famous composer of this genre was unquestionably Stephen Foster, whose hits, “Oh! Susanna” (1848), “Camptown Races” (1850), and “Swanee River” (1851) — all of which became American standards — were “blackface” songs. Simpson co-opted these melodies, matching, for example, the words of “I’m on My Way to Canada” to the melody and tempo of “Oh! Susanna.” As Simpson explained in 1852, “My object in my selection of tunes, is to kill the degrading influence of these comic Negro Songs […], and change the flow of these sweet melodies into more appropriate and useful channels.” In this way, Simpson sought to transform these songs from instruments of subjugation and repression into forces to help achieve liberation.

Canada is a central and recurring theme in Simpson’s songs and is even the focus of some of them. For example, the narrator of “I’m on My Way to Canada” describes his escape from a cruel plantation owner to reach faraway Canada “where coloured men are free” and where a benevolent sovereign awaits him with open arms. Similarly, the songs “The Final Adieu” and “The Son’s Reflections” — adapted to the tunes of “Camptown Races” and “Swanee River” respectively — relate the desire of slaves in the American South to break their chains and escape to British North America. These songs expressed and, through public performance, conveyed an image of Canada as a destination both real and mythical for those seeking freedom in the mid-19th century. They are both artifacts of a protest movement and hymns to freedom.

John Willis and Tim Foran

Canadian Museum of History