Forty-six years ago, in November 1973, Superior Court Judge Albert Malouf set off a shock wave by finding in favour of a demand by Inuit and Cree. The decision forced the Quebec government to interrupt construction of hydroelectric dams at James Bay, and to negotiate.

The ruling was greeted with astonishment and with consternation in some cases. It was viewed by some as an aberration. Others saw it as a stroke of genius, empathizing readily with the victims of this major project. One thing is certain: the earth began to shift, setting off a seismic wave previously unlikely on the Canadian Shield.

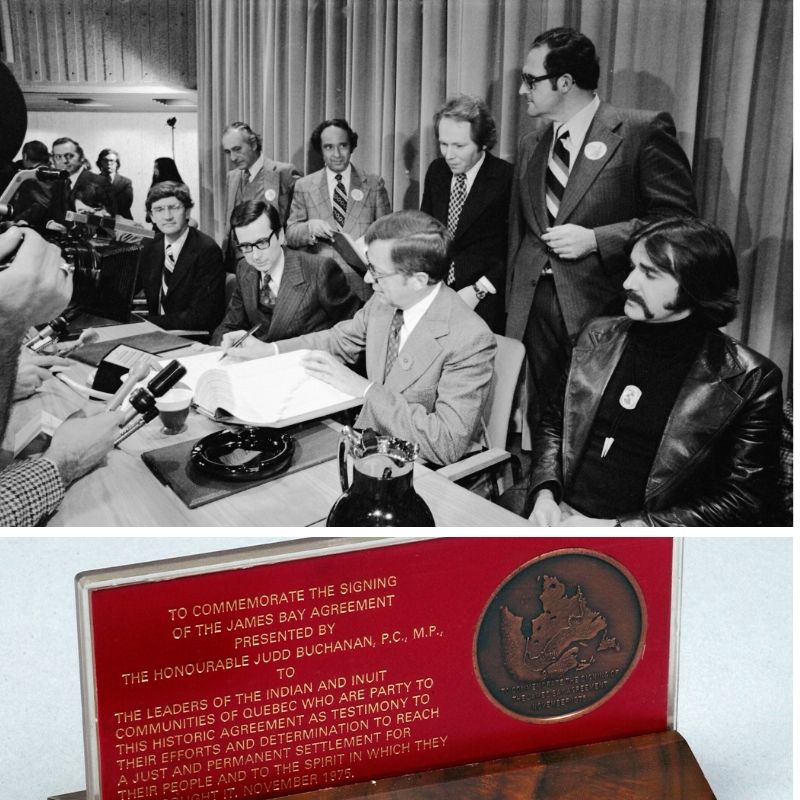

The decision of Jean Chrétien, federal Minister of Indian and Northern Affairs, to grant Indigenous Peoples a subsidy to help with their defence was not applauded by everyone, but it certainly benefitted the plaintiffs. And, after numerous twists and turns, an agreement was signed on November 11, 1975: the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement (JBNQA). It was a heroic tour de force through which Cree and Inuit would change the course of Canadian history.

Up: The signing of the James Bay Agreement. Photo: Hydro-Québec, 75-12812-19

Down: Commemorative medallion celebrating the signing of the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement. Canadian Museum of History, I-A-1036 a-b. Gift of John C. Moses

But let’s take a step back. In April 1971, Quebec Premier Robert Bourassa surprised everyone when he announced the “project of the century,” the most ambitious hydroelectric network ever to be built in the Western world. The proposed project was driven by a passion for progress, the pride of a people, a shortage of energy and the promise of 100,000 jobs — who would dare to face down this juggernaut? Was it an act of courage or folly? As summed up so well in the title of the book by Zebedee Nungak, it was a struggle against colonialism run amok: Wrestling with Colonialism on Steroids: Quebec Inuit Fight for Their Homeland (Véhicule Press, 2017).

This is why, at the beginning of the saga, no one could have predicted that a group of young Cree and Inuit — representing barely 9,000 people — would be able to convince the government to sign the first modern treaty in North America constituting a settlement between Indigenous Peoples and a government. A mere few years earlier, this had been a distant reality in Canada.

“In 1969, as a government employee, they moved me to Kangiqsualujjuaq. I wrote a letter to John Diefenbaker, the opposition leader in Parliament. I was summoned to Ottawa. Up there, the government people told me I had no rights. They said only one person should represent Inuit: Bishop Donald Marsh, ‘Donald of the Arctic.’ Only a white man had the right to speak for the Inuit.” Senator Charlie Watt, signatory to the JBNQA. Source: Napagunnaqullusi (So That You Can Stand!)

“The governments always told the Cree, ‘You have no rights; you are squatters.’” Grand Chief Billy Diamond, signatory to the JBNQA. Source: Together We Stand Firm

If, at the time, this action was seen as resistance to progress, it should be recognized that today it is the exact reverse. The JBNQA was, in reality, a giant step that the country took toward a modern outlook. Not only had the players around the negotiation table evolved, but an entire country had as well. The fallout from the agreement was immeasurable throughout Canada, and perhaps elsewhere in the world.

As an archaeologist, I must emphasize how much the JBNQA contributed to the development of a better archaeological ethic. For the first time, Indigenous groups —Cree and Inuit — would take greater control of their cultural heritage. At the beginning of the 1980s, they became pioneers of a process that is still under way among numerous Indigenous groups in Canada and around the world.

“Until now, any archaeologist … did their thing, then left for the rest of the year, even if the natives weren’t sure what went on. The Inuit should be consulted properly before any work is done on their territory…

“In their territory, the Inuit have the right to an overall say and control on anything that will affect them the most, because it is where they make a living — off the land, although not as totally as they used to.

“This signed agreement with Canadian and Quebec governments, in case of Northern Quebec Inuit will undoubtedly give them more say in all aspects of their lives.”

Daniel Weetaluktuk, 1978. Source: Canadian Inuit and Archaeology

Dr. Pierre Desrosiers is Curator, Central Archaeology at the Canadian Museum of History.