Samuel de Champlain took a new approach to interacting with local populations. It made possible the establishment of a permanent French presence in North America.

The history of encounters between Europeans and First Peoples in Canada throughout the 1500s was marked by a disregard, on the part of Europeans, of Indigenous rights and interests. Champlain, in contrast, built alliances and nurtured positive relationships.

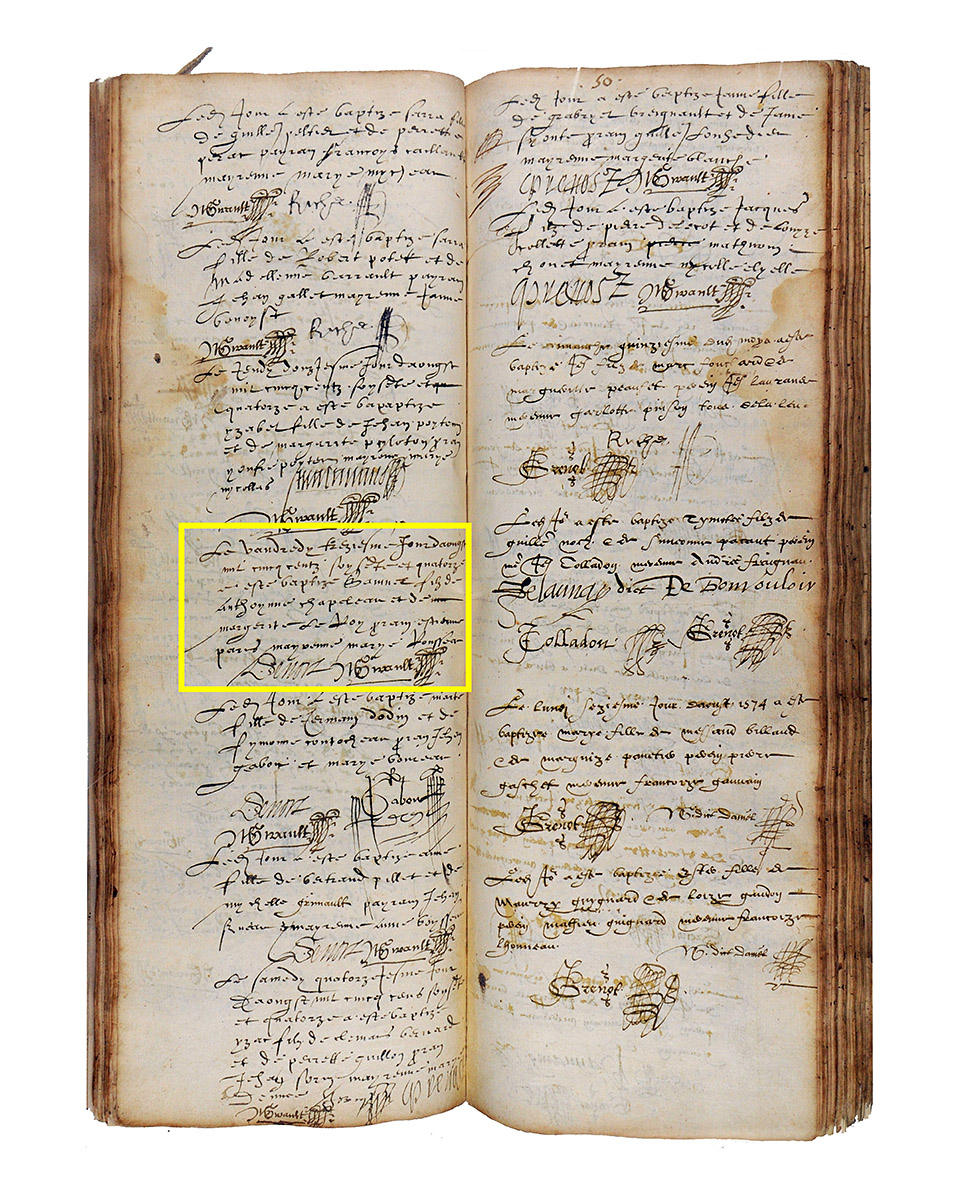

Champlain’s baptismal record?

Much about Samuel de Champlain, including his appearance, remains a mystery. He is believed to have been born in La Rochelle, France, about 1570. His family was probably Protestant, although Champlain later converted to Catholicism. He joined the French military in 1594 and, five years later, crossed the Atlantic Ocean for the first time on a voyage to the Caribbean. He first sailed to North America in 1603 and would eventually serve as lieutenant-governor of New France, until his death on December 25, 1635.

Image: Parish Records of the Church of St-Yon, La Rochelle, France, 1574

Archives départementales de la Charente-Maritime, France, I 144(I 11)

Transcription translated in English: “On Friday the thirteenth day of August, in the year fifteen hundred seventy-four, Samuel son of Anthoynne Chapeleau and of m [word crossed out] Margerite Le Roy, g[o]dfather Estienne Pare, godmother Marye Rousseau. Denors N Girault.”

Champlain, The Observer

During his travels to the Americas, Champlain encountered many new and wondrous things: landscapes, animals, plants and people. He recorded much of what he saw and experienced. Travelling through the Caribbean for the King of Spain, he witnessed the Spanish mistreating the First Peoples. When his turn came to lead expeditions to the Americas and establish a settlement for the King of France, Champlain adopted a different approach altogether.

In addition to maintaining an extensive correspondence, Champlain published four books between 1603 and 1632, recording his observations and impressions of Canada. He may have used this inkstand, found in Québec City, in his writing and drawing. To learn more, you can visit the website of the Quebec Ministry of Culture and Communications.

Drawings of the Spanish treatment of the Native people

From Samuel de Champlain, Bref discours des choses plus remarquables …, about 1602 Courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library at Brown University, United States, 04684-76

Library and Archives Canada, e01076473

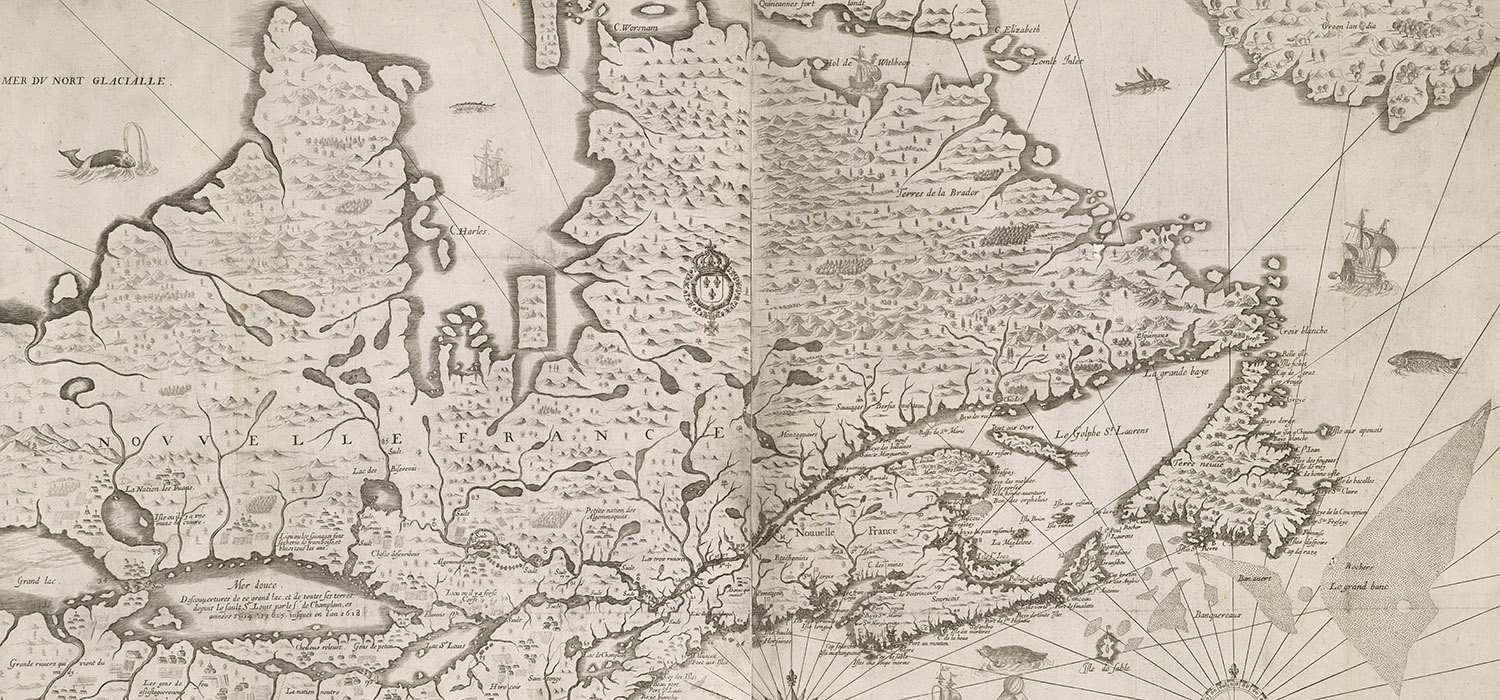

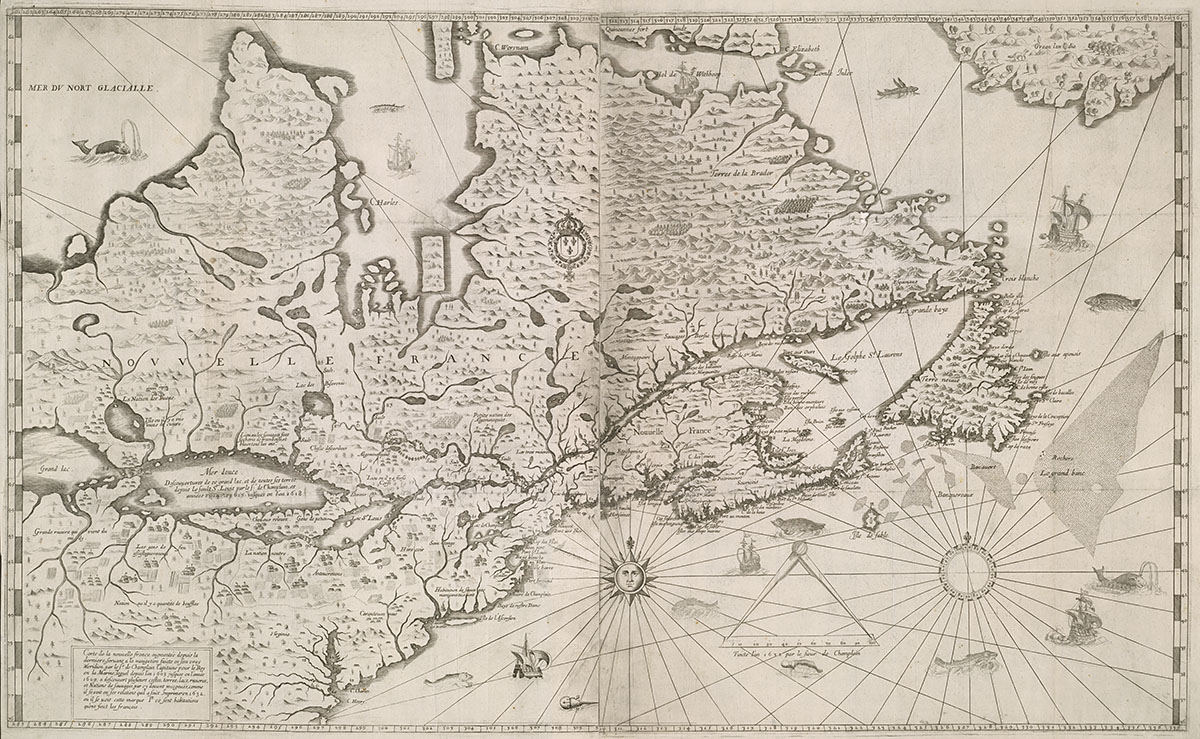

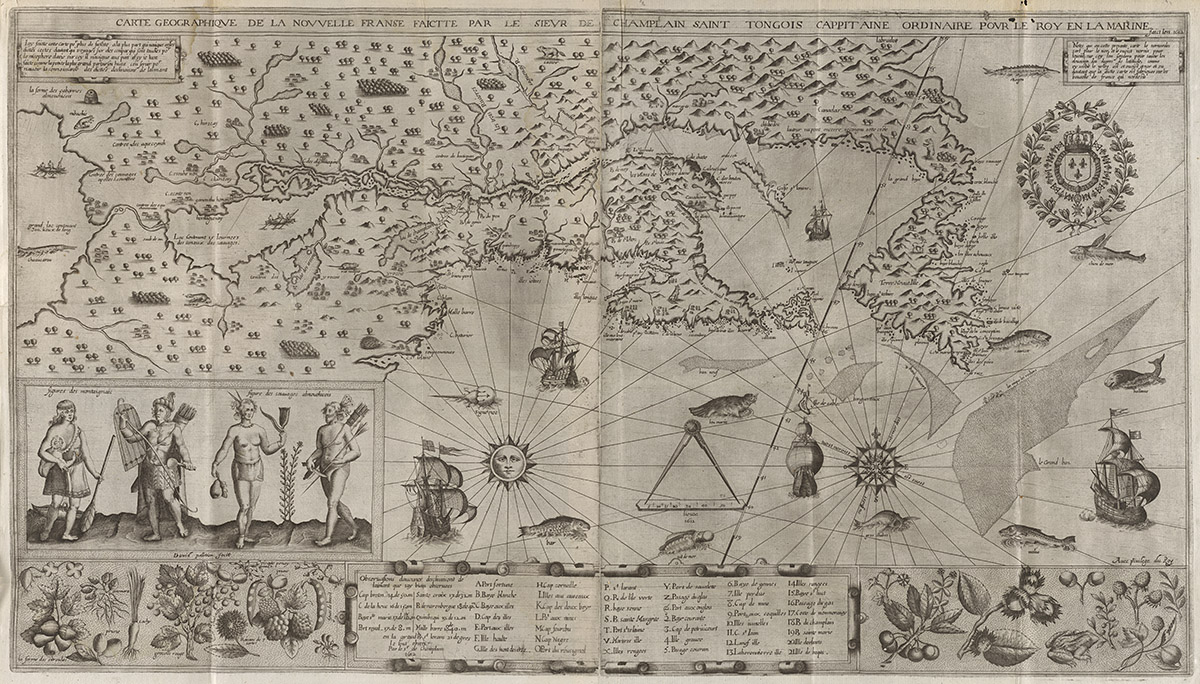

“Carte geographique de la Nouvelle Franse faictte par le Sieur de Champlain Sait Tongois Cappitaine Ordinaire pour le Roy en la Marine. Faict len 1612.”

“Geographical map of New France by Sir Champlain Saint Tongois, the King’s Captain at Sea. Made in 1612”

From Samuel de Champlain, Les voyages du sieur de Champlain Xaintongeois, 1613

Champlain, The Diplomat

Samuel de Champlain had witnessed the conditions that Indigenous peoples endured under Spanish rule and was aware that French diplomacy had failed in the past. At Tadoussac, when he found himself before a large encampment of First Peoples, including Innu, Anishinabeg (Algonquin) and Wolastoqiyik (Maliseet), he chose to engage them as equals in nation-to-nation discussions. Champlain and the First Nations formed a mutually beneficial alliance that would mark the future of the new French colony.

Image: Drawing of Cheveux relevés, Odawa (detail)

From Samuel de Champlain, Les Voyages de la Nouvelle France occidentale, dicte Canada, 1632

Library and Archives Canada, AMICUS 10310924

Objects from the site in Cahiagué, Ontario, where Champlain overwintered in 1615–1616

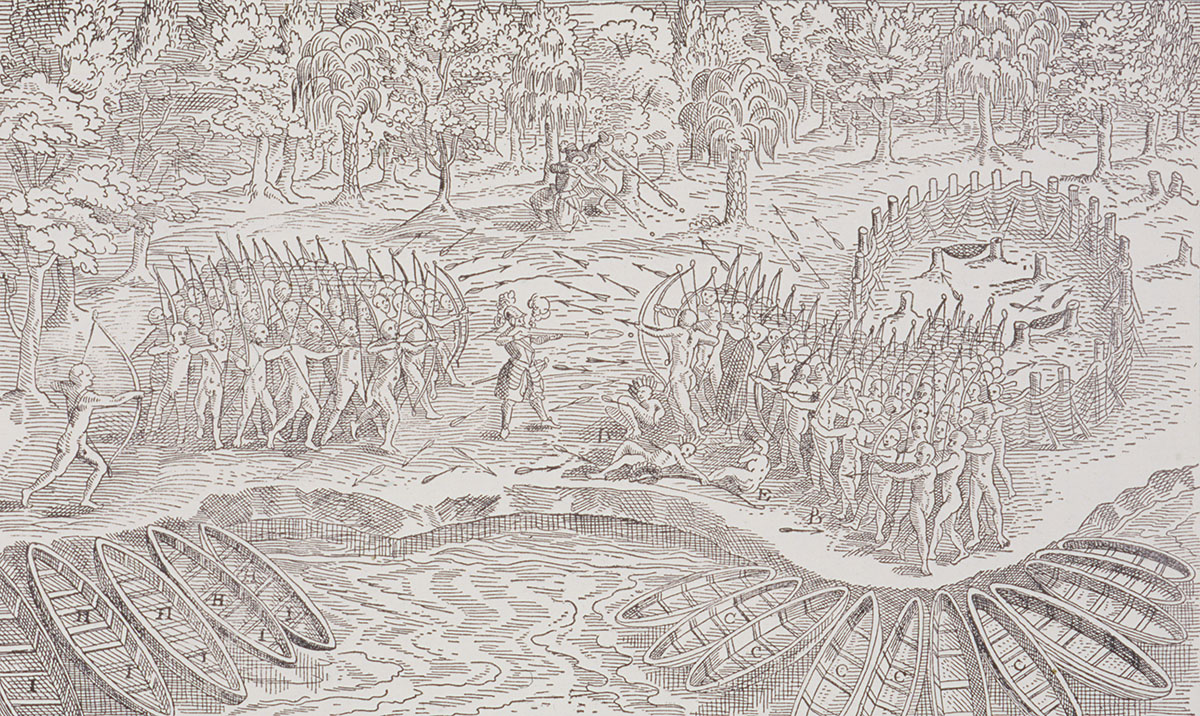

The Defeat of the Iroquois at Lake Champlain (detail)

From Samuel de Champlain, Les voyages du sieur de Champlain Xaintongeois, 1613 CMH, S94-13225-Dm

Champlain, The Soldier

Champlain and the French joined an existing alliance between the Innu, Anishinabeg, Wolastoqiyik, and the Huron–Wendat. As early as 1609, Champlain was following Indigenous alliance practices and fighting alongside his new allies as they battled their Haudenosaunee, or Iroquois, enemies.

Champlain, The Cartographer

Between 1599 and 1633, Samuel de Champlain crossed the Atlantic nearly thirty times and travelled thousands of kilometres on inland waterways. He created detailed maps based on his own observations of the geography and on information provided by First Peoples allies.

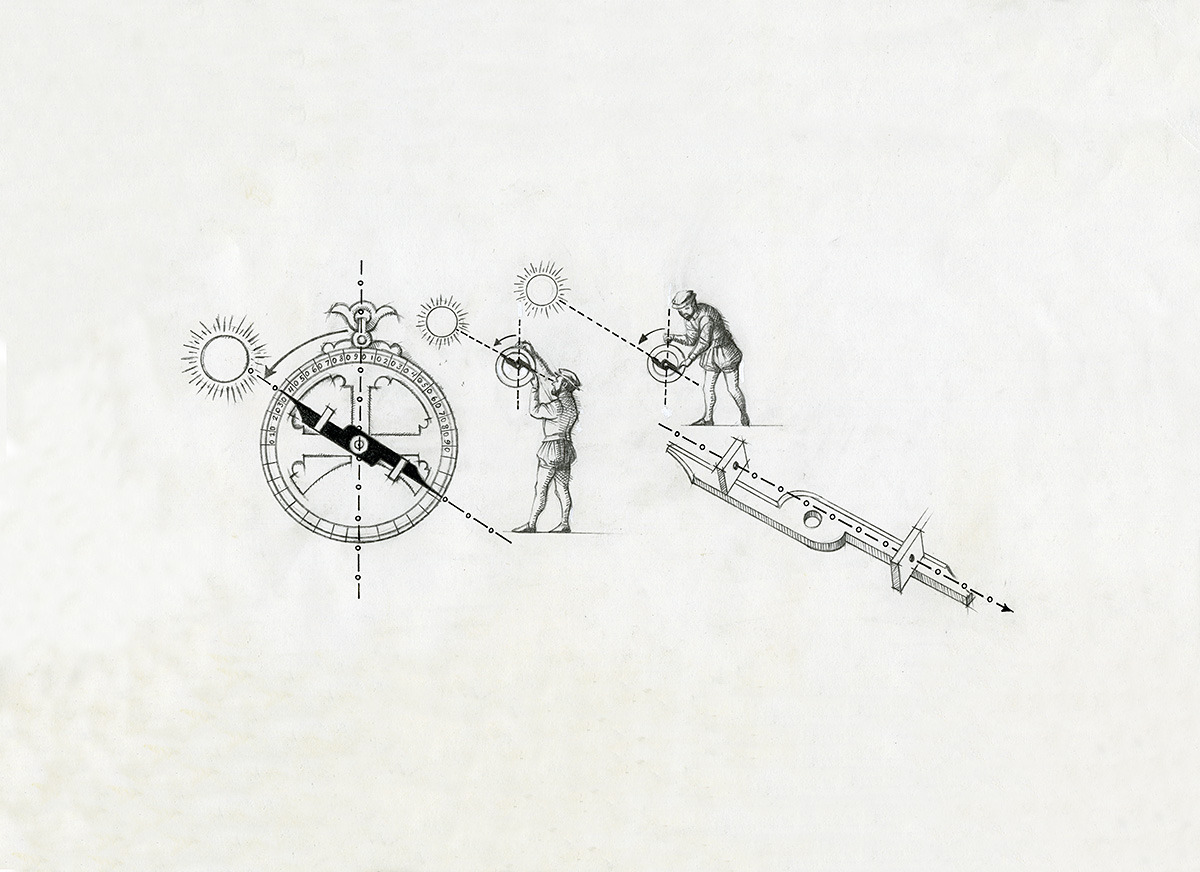

Champlain’s Astrolabe?

This mariner’s astrolabe, used to determine latitude, was found along a portage known to have been used by Samuel de Champlain. Although popularly linked to him, the astrolabe is not sophisticated enough to have provided the accurate measurements that generally characterize his maps — although it may have been a spare. It was found along with copper saucers, silver cups and a length of steel chain, all now lost. It’s more likely that these items belonged to a Catholic missionary. So was this really Champlain’s astrolabe? The question remains.

Champlain, The Settler

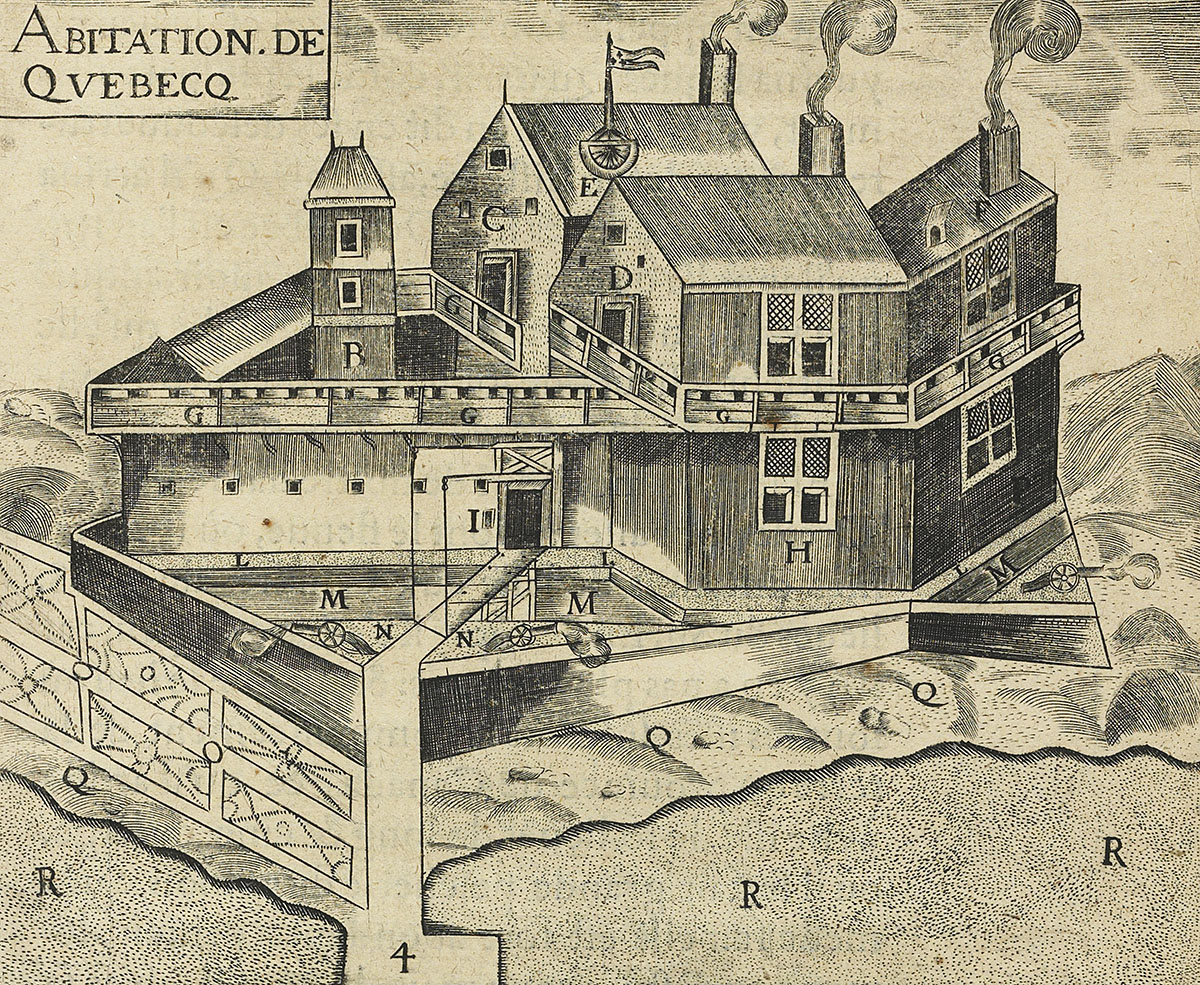

For more than a hundred years, European interests had centred on the seemingly limitless resources of the sea, but animal furs were of growing interest. With new allies at his side, Samuel de Champlain established a permanent base that would facilitate the fur trade while also allowing him to pursue his explorations in the quest for the elusive passage to Asia. This permanent foothold became the nucleus around which New France would be built.

Habitation at Quebec (Detail)

From Samuel de Champlain, Les voyages du sieur de Champlain Xaintongeois, 1613 Library and Archives Canada, e010774131