The story of the Franklin Expedition is familiar to many Canadians, and to many people around the world. An Arctic expedition, comprising 128 men under the command of Sir John Franklin, departed in two ships from Britain in May 1845 with the task of fulfilling a 400-year-old dream — charting a Northwest Passage through the Arctic Archipelago from the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean.

The Expedition spent its first Arctic winter near Beechey Island, where three men died and were buried. Their bodies, autopsied in 1984 and 1986, preserved evidence of lead poisoning and tuberculosis, early signs that all was not well aboard the expedition’s ships.

What happened after Franklin’s expedition left Beechey Island is still unclear. One expedition document, discovered near Victory Point on King William Island, reported the death of Sir John Franklin on June 11, 1847; desertion of the ice-beset ships on April 22, 1848; and the intention of the remaining 105 crewmen to walk to the mainland. None survived; their fate remembered by Inuit, who saw sick and starving men trekking south and later found their bodies, some bearing unmistakable evidence of cannibalism.

There is a widespread perception that the expedition was composed of nameless men, poorly equipped for land travel, who suffered and died in horrible circumstances. This is unfortunate because it obscures the fact that each crewmember was someone’s husband, father, son, brother or uncle.

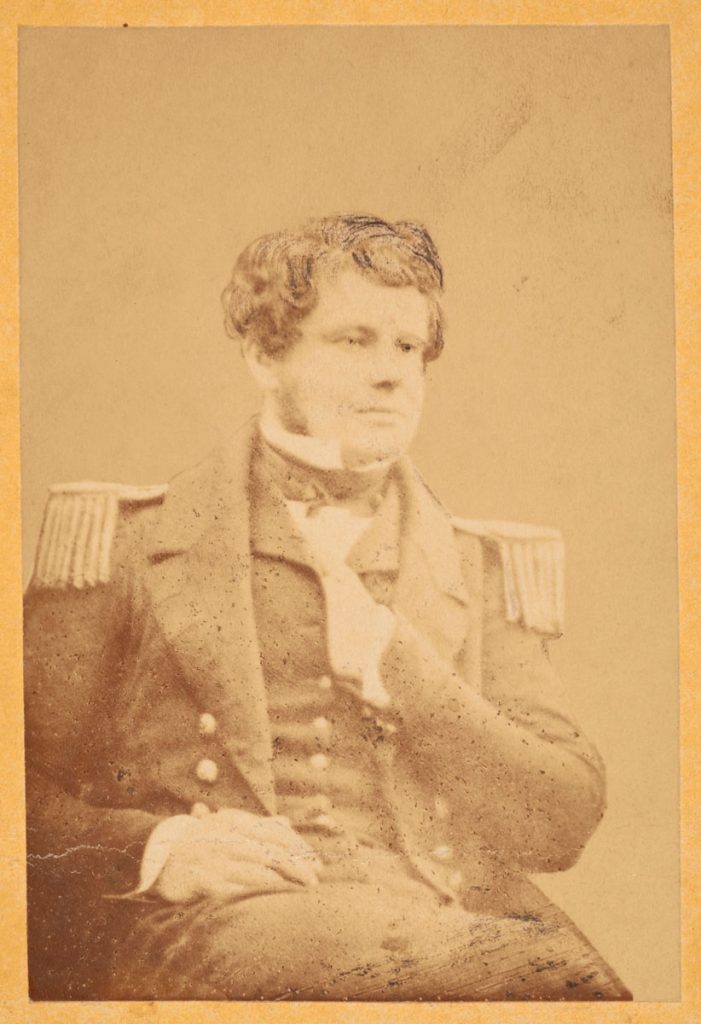

Salt print of Lieutenant Fairholme’s daguerreotype portrait. Canadian Museum of History, Lieutenant Fairholme’s collection, 2016-H0010.

But for the modern-day relatives of Lieutenant James Walter Fairholme, the tragedy of the expedition is still present, even after 172 years.

Lieutenant Fairholme was considered “a smart, agreeable companion, and a well-informed man” by Commander James Fitzjames, his senior officer on HMS Erebus. Fairholme, like Fitzjames and the other Erebus officers, had his daguerreotype portrait taken before leaving Britain (consult Russell Potter’s blog to learn more); 12 of these daguerreotypes survive at the Scott Polar Research Institute.

In researching those images, William Battersby recognized that some officers actually had a second portrait taken, a fact confirmed by Lieutenant Fairholme in a letter written to his father in May 1845:

“I hope Elizabeth [James’ sister] got my photograph. Lady Franklin said she thought it made me look too old, but as I had Fitzjames’ coat on at the time, to save myself the trouble of getting my own, you will perceive that I am a Commander! and have anchors on the epaulettes so it will do capitally when that really is the case.”

Although the original daguerreotype is now lost, the Fairholme family had a salt print made during the 19th century. This image, along with Lieutenant Fairholme’s posthumously awarded Arctic Medal 1818-1855, was kept inside a small custom-made case with a silver dessert fork that Lieutenant Fairholme took aboard Erebus.

Dessert fork and Arctic Medal in a case. Canadian Museum of History, Lieutenant Fairholme’s collection, 2015.46.1.1; 2015.46.1.2 a-b; 2015.46.1.3, IMG2016-0321-0015

These mementoes of his life were carefully passed down through his family until they were recently acquired by the Canadian Museum of History. The Lieutenant James Walter Fairholme Collection will be publicly displayed for the first time when the Franklin Exhibition opens at the Museum on March 2, 2018.