Much like everything else, my ability as a Museum curator to do archaeological fieldwork has been impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. Non-essential travel into Inuit Nunangat — the Inuit homeland in Canada — was restricted for a period to help protect people living in the North, for whom access to more comprehensive health care usually means taking a long trip to a southern hub like Ottawa.

As travel restrictions relaxed earlier this year, I began planning our first field season since 2019, alongside the Avataq Cultural Institute, Makivik Corporation, and Northern Village of Kangiqsujuaq.. Together, we have been focusing on the Qajartalik petroglyph site, located about 40 km southeast of the community of Kangiqsujuaq (formerly Wakeham Bay), Nunavik, where approximately 180 human and human-like faces were carved into soapstone outcrops.

[Left] Map of Nunavik’s 14 communities, including Kangiqsujuaq — the closest village to Qajartalik.

Map source: keac-ccek.org/en/impact-assessment-in-nunavik

[Right] Qikiqtaaluk Island and Qajartalik (lower right) are about 40 km southeast of Kangiqsujuaq.

Map source: atlas.gc.ca/toporama/en/index.html

Fieldwork and the COVID-19 pandemic

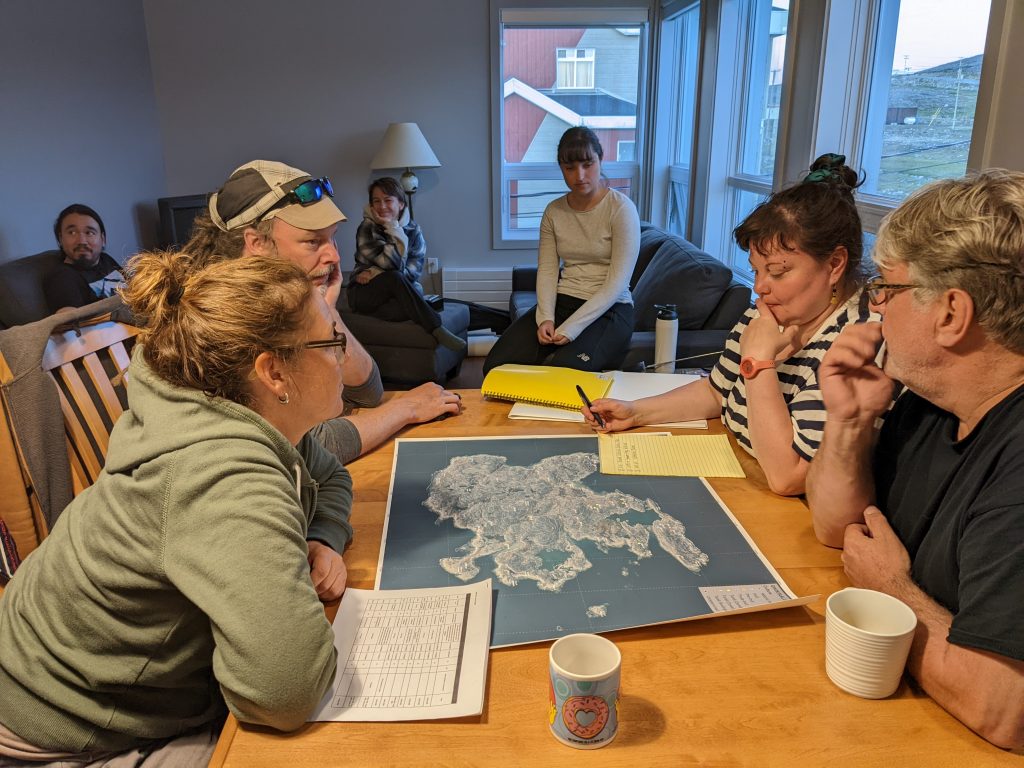

Planning the next day’s work. Clockwise from bottom left: Susan Lofthouse (Avataq), Richard Lapointe (Expertise laser 3D – iSCAN), Nicolas Pirti-Duplessis and Élise Legault (both Avataq), Catherine Caya-Bissonnette (Expertise laser 3D – iSCAN), Elsa Cencig (Avataq), and Robert Fréchette (Makivik).

Unlike in normal years, when we would ordinarily live in a camp for around a month near the sites we’re studying, we planned a short field season of 10 days this year because we weren’t sure whether the pandemic would require us to cancel our fieldwork at short notice. We also didn’t want to put ourselves or anyone else at undue risk if someone in camp contracted COVID-19. Given these uncertainties, we opted to base ourselves in Kangiqsujuaq, then travel to Qajartalik by helicopter for five days.

[Video 1] En route to Qajartalik by helicopter.

A future UNESCO World Heritage Site

One of the laser scanners at Qajartalik.

The Canadian federal government updated its tentative list for UNESCO World Heritage sites in 2017, adding eight new locations, including Qajartalik. Our focus this year was to work with a laser scanning team to create a detailed 3D digital map of the site, including a main area that is over 130 m in length (excluding several outlying locations), which will help us study and monitor Qajartalik. The 3D model will also make it easier to see how the petroglyphs appear to change as the light shifts daily and seasonally. This is important because we need to consider who might have been meant to see the faces, and when. Beyond this, the 3D model will be a tremendous asset for documenting the number, location and style of faces, especially since many are now difficult to see.

The faces depicted at Qajartalik take different forms and were made using different techniques, but they all share basic similarities, including eyes, noses and mouths. Each is defined by an engraved outline that gives a face its shape, although some are now very faint because of weathering (erosion).

While organic preservation is poor, making it difficult to find materials suitable for radiocarbon dating, we do know that the Qajartalik faces were created by a now-vanished PalaeoInuit people called Dorset by archaeologists and Tuniit in Inuit oral histories. Based on comparisons with sites elsewhere in the Arctic, we believe the petroglyphs were made between 1,500 and 750 years ago, although we continue to work to confirm this.

![[Left] A well-defined face at Qajartalik. [Centre] A cluster of faces. [Right] Faces on the soapstone outcrop.](https://history-museum.cinnamonstaging.ca/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/Blog-KRyan-09-2022_Fig567-1024x512.png)

[Left] A well-defined face at Qajartalik.

[Centre] A cluster of faces.

[Right] Faces on the soapstone outcrop.

![[Left] An eroding face. [Right] An almost-vanished face.](https://history-museum.cinnamonstaging.ca/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/Blog-KRyan-09-2022_Fig89-1024x512.png)

[Left] An eroding face.

[Right] An almost-vanished face.

Portable carvings

With only a few exceptions, Tuniit carvings of people and other animals — like bears and walruses — are quite small and portable, and could easily have been held in the hand or carried in a container. They were made using materials such as ivory, antler and wood, and some carvings have polish or wear marks, indicating that they were handled frequently. The exceptions to this hand-sized rule include two full-sized wooden masks that are now on display in the Canadian History Hall, as well as the Qajartalik faces.

![[Left] A small ivory maskette excavated from a site near Salluit, Nunavik. [Centre] A human-like figure excavated near Pond Inlet (Mittimatalik), Nvt. [Right] One of two full-sized wooden masks excavated from Bylot Island, Nvt.](https://history-museum.cinnamonstaging.ca/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/Blog-KRyan-09-2022-1024x512.png)

[Left] A small ivory maskette excavated from a site near Salluit, Nunavik (KbFk-7:308).

[Centre] A human-like figure excavated near Pond Inlet (Mittimatalik), Nunavut (PgHb-1:9083).

[Right] One of two full-sized wooden masks excavated from Bylot Island, Nunavut (PfFm-1:728).

![[Left] An antler “wand” covered with faces, excavated from Bathurst Island, Nunavut (QiLd-1:2020). [Right] An antler “wand” with faces, excavated from Ellesmere Island, Nunavut (SiHw-1:788).](https://history-museum.cinnamonstaging.ca/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/Blog-KRyan-09-2022-1-1024x512.png)

[Left] An antler “wand” covered with faces, excavated from Bathurst Island, Nunavut (QiLd-1:2020).

[Right] An antler “wand” with faces, excavated from Ellesmere Island, Nunavut (SiHw-1:788).

My role in this collaborative and community-based work is to help investigate why, when and how Tuniit craftspeople carved faces into Qajartalik’s soapstone and at two much smaller nearby sites. We are also focused on better understanding how the petroglyphs fit within the Tuniit’s local cultural landscape, as well as within their larger world. We were able to briefly visit and test some non-petroglyph sites near Qajartalik to continue this part of the project.

![[Left] Test excavations at a Tuniit (Dorset) site near Qajartalik. [Right] Inspecting a Tuniit (Dorset) site. Qajartalik is in the far distance, behind the archaeologists.](https://history-museum.cinnamonstaging.ca/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/Blog-KRyan-09-2022-Fig16-17-1024x512.png)

[Left] Test excavations at a Tuniit (Dorset) site near Qajartalik.

[Right] Inspecting a Tuniit (Dorset) site. Qajartalik is in the far distance, behind the archaeologists.

Ongoing work

We’re hoping to resume a more typical field season in 2023, camped near the sites we have targeted for investigation. Our long-term goal is to support Qajartalik’s bid for UNESCO World Heritage Site status by exploring what were no doubt complex social, and probably ritual, relationships involving the petroglyphs, and Tuniit “art” more generally. While many aspects of Tuniit life will remain archaeologically invisible, Qajartalik was unquestionably an important location within an archaeologically complex area.

We already know that Tuniit from across the region gathered periodically for social and economic purposes near Qajartalik. One of our jobs is to identify and consider that complexity to better understand how Tuniit groups might have envisioned their world and their relationships with one another through time and across their physical and cultural environments. It is only once we have done that that we can then begin to appreciate why Qajartalik was created.

Further reading

- The Northern Limit of Human Occupation — a story about the Dorset, from the Canadian History Hall

Karen Ryan

Karen Ryan is the Curator for Northern Canada at the Canadian Museum of History. Her responsibilities include studying the Museum’s northern archaeological collections, which are the largest at the Museum. She does work in the field to excavate and study archaeological sites as part of a larger effort to better understand the human history of the Canadian North.