Black hockey has a longer history in Canada than you might expect. It’s a story shared in Artifactuality, a podcast series that imagines a museum of the future made up entirely of the stories we tell each other. In the episode “Breaking Ice,” we talk to Nova Scotia community leader Elizabeth Cooke-Sumbu about her grandfather Frank Cooke, a star of the Coloured Hockey League of the Maritimes (CHLM), and to politician Percy Paris, who recalls his formative years playing pond hockey and the challenges he faced as a young Black hockey player. We also delve deeper into the story of the CHLM, which was recently celebrated on a postage stamp and in the documentary Black Ice. Yet many details about the CHLM remain unknown: who were the men who played in the league and what happened after it ceased to exist around 1935?

Download and subscribe to Artifactuality: Stories From the Museum of the Future wherever you get your podcasts.

Elizabeth Cooke-Sumbu

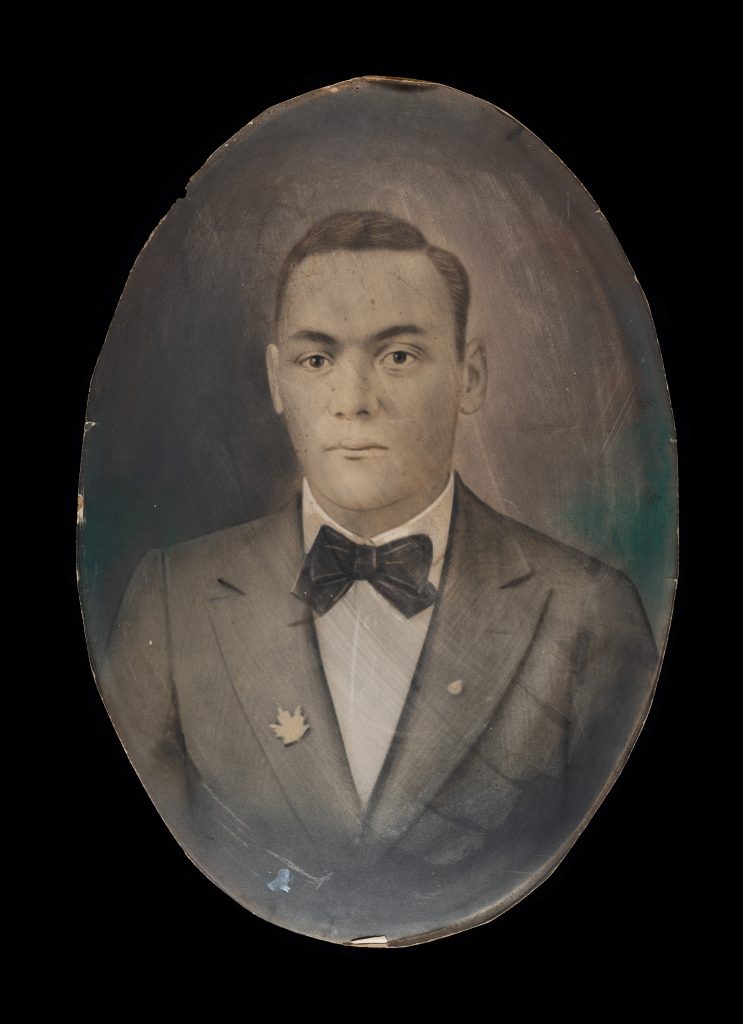

A Surprising Family History

Elizabeth Cooke-Sumbu was surprised when she learned that her grandfather, Frank Cooke, played in the CHLM. Like many other men of his generation, Frank didn’t talk much about his time in the league. For this reason, the remarkable story of the all-Black men’s hockey league remained mostly forgotten until family members began to dig into its history. Over the last 20 years, the descendants of former players, like Elizabeth, along with historians, have started to piece together the story of the pathbreaking league and its role in Canadian sport history. It was a challenge, since players didn’t often leave behind their hockey sweaters or paper records of their experience. Elizabeth did have this treasured family photo of her grandfather, who was a star of the CHLM Amherst Royals and a First World War veteran who died in the 1960s.

Portrait of Frank Silliker Cooke.

Canadian Museum of History 2022.20.1

The Coloured Hockey League of the Maritimes

The Coloured Hockey League of the Maritimes, or CHLM, was founded in 1895 by Black church leaders in Nova Scotia to bring young Black men to the church, and soon expanded to Prince Edward Island and New Brunswick. At its peak in the first few years of the 1900s, the CHLM had more than 100 players and 12 teams including the Dartmouth Jubilees, the Africville Sea-Sides, the Amherst Royals, and the Charlottetown West End Rangers.

The playing style of the league was reported to be fast, physical and innovative. Members of the league are credited with pioneering techniques that are now commonplace in modern hockey: Eddie Martin is said to have developed an early form of the slapshot, and Henry “Braces” Franklin was known for dropping to his knees to stop the puck, a move now known as “the butterfly.” Many descendants of CHLM players emphasize the league’s importance in bolstering camaraderie among players and Black communities in Eastern Canada.

The 1921 Africville Sea-Sides.

Nova Scotia Sport Hall of Fame, Artifact 995.05.01

The Colour Barrier

The existence of a hockey league for Black men challenges the idea that hockey is for everyone. Many groups have historically played the sport in Canada, but not necessarily together. While there were not many laws permitting segregation in early 20th century Canada, segregationist local customs shaped where people lived, played and went to school. Elizabeth remembers of her childhood:

“We had places where we could go and could not go. You didn’t go to the restaurants. If you went to the theatre, there was a section where you had to sit. We had our own Black church. There were certain areas where you were buried. We have several graveyards here in our community where the Blacks were all buried at the back.” — Elizabeth Cooke-Sumbu

The End of the CHLM

The league experienced several ups and downs during its existence and CHLM teams were often restricted to less-than-prime ice time that shortened the length of their playing season. By the late 1930s, the Great Depression and the onset of the Second World War contributed to the demise of the league. But Black men were still playing hockey. Fredericton’s Willie O’Ree is the most high-profile example. He became the first Black player in the NHL when he joined the Boston Bruins in 1957. But we also know there was continuity because of the new generation of players who came to prominence in the 1960s and 1970s.

Pond Hockey and “Rink Rats”

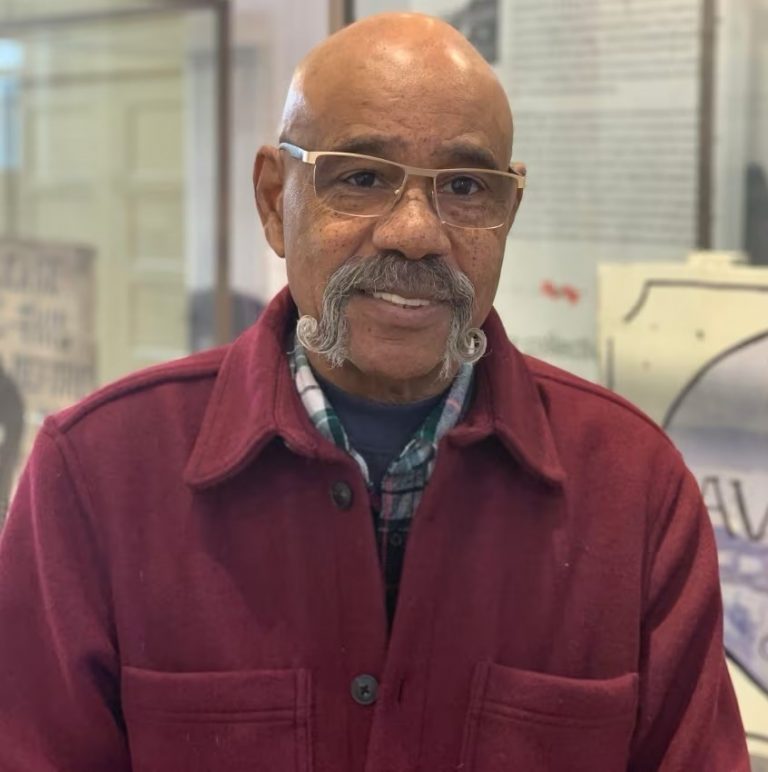

Percy Paris grew up playing sports and credits his father with making sure the family played baseball in the summer and hockey in the winter. Percy developed skill and agility playing pond hockey in the 1950s and 1960s. A self-described “rink rat,” he also spent a lot of time at the local hockey rink. Here, he was able to see games for free and made use of free ice time to play scrimmages with friends. The community tradition of hand-me-down and used equipment from friends and older siblings allowed Percy and others to offset the prohibitive costs of playing hockey.

When they weren’t on the ice or watching games, Percy and his friends pored over The Hockey News to see who had scored goals. They scanned the pages for news about fellow Black players like Willie O’Ree, along with Herb Carnegie and Stan “Chook” Maxwell who were well known players in the Quebec Junior Hockey League. Percy was inspired by these players to pursue a professional hockey career and he later found out that Maxwell was a distant relative.

“As a youth, for those of us of African descent, we look for heroes who look like us.” — Percy Paris

Percy Paris.

Stan “Chook” Maxwell

Nova Scotia Sport Hall of Fame, Artifact 996.225.01

Percy Paris and the First All-Black Line

When he initially failed to make the St. Mary’s University Huskies hockey team, Percy continued playing in different leagues in the Halifax area. In 1970, when the call finally came to suit up with the Huskies, Percy, along with Bob Dawson and Darrell Maxwell, became part of the first all-Black line in university hockey history. Despite his achievements, Percy and fellow Black players were still subject to the racial slurs and taunts that were common at the time.

“For years and years and years, I played competitive gentlemen’s hockey. I say gentlemen’s somewhat with tongue in cheek. A lot of the games weren’t very gentlemanly. There were still racial slurs being directed my way.” — Percy Paris

Though Percy and Elizabeth acknowledge that race relations in the Maritimes have improved, they both insist that there is more work to be done. Along with the persistence of racism, the high price of registration and equipment is still a systemic barrier to participation for many would-be players from marginalized communities.

The New History of Hockey

Sport can be a source of national pride, but it can just as often mirror the divisions in society. The CHLM and the accounts of Elizabeth and Percy remind us that the history of sport in Canada goes deeper than the stars of professional leagues. The CHLM is more than just a historical curiosity. Instead, it illustrates an unjust and persistent gap in the historical record of hockey. It also shows us that the unexpected and exciting aspects of hockey don’t only happen on the ice — they are embedded in the history of the sport and the stories of those who played before us.

Related Content

- Commemorative Stamp pays tribute to all-Black hockey league in the Maritimes

- Black Ice Documentary Trailer

- 2017 Canadian Museum of History Hockey Exhibition – Original video on hockey

- Canadian Museum of History Travelling Hockey Exhibition

- Hockey History Trivia Challenge

- Canadian Museum of History Publications

- Hockey exhibition souvenir catalogue

- Hockey, from the Mercury Series

Download and subscribe to Artifactuality wherever you get your podcasts — Apple Podcasts, Spotify and Google Podcasts — or listen on YouTube.

Learn more about other episodes of Artifactuality:

- The Meaning of Mitsou – A conversation about stardom, style and reinvention

- We Have Always Been Here – Conversations with Blackfoot Elders about archaeology, and territory

- Hearts of Freedom – A new perspective on Southeast Asia’s refugee crisis

- Prince of Plastic – How Karim Rashid advanced democratic design

Daniel Neill

Daniel Neill is the Researcher for Sport and Leisure at the Canadian Museum of History. He is also a musician and PhD Candidate in Ethnomusicology at Memorial University of Newfoundland.