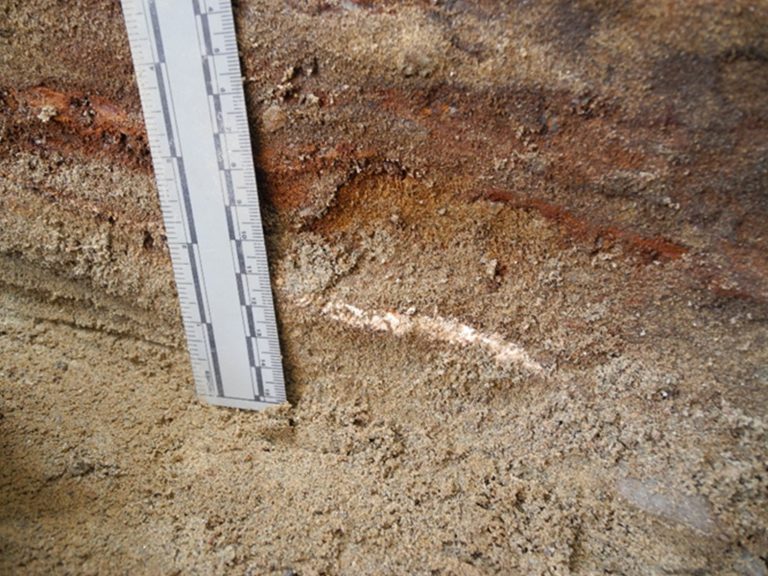

On the last day of excavations in the lot behind 62 Sparks Street, while digging a hole to get a good stratigraphic profile of an area of disturbance, a hollow thump was heard. Further investigation by lead archaeologist Ben Mortimer (Matrix Heritage) revealed that beneath a darkened deposit of sand, cinder, clinker, coal and refuse, sat a strange metal box.

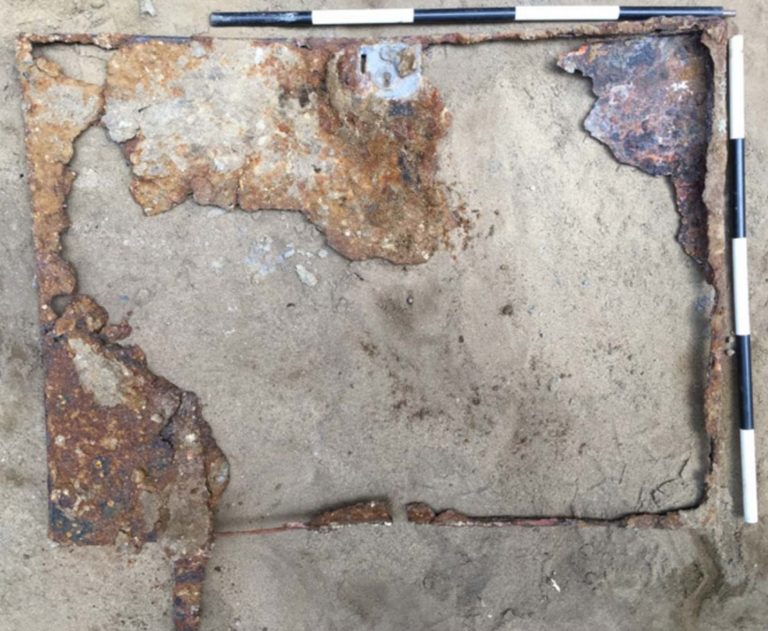

It was closed with a lock, suggesting that it may have been some sort of safe or insulated chest, and that it possibly dated back to the late 19th or early 20th centuries. Removal of dirt and portions of the door revealed that the box held human skeletal remains.

The metal box in situ prior to excavation

(Mortimer, 2017)

Close-up of lock securing box lid

(Mortimer, 2017)

After the remains were transferred to my lab, I was able to begin sorting the jumbled array of bones and grouping like remains into individual skeletons. By the end of this exercise, at least 15 individuals, including a minimum of five children and 10 adults, were identified. The subadult remains were some of the only ones found during the 2016 excavations.

Metal box in situ with the lid open

(Mortimer, 2017)

It would appear that sometime around the turn of the century, human remains were discovered while excavating the back lot of 62 Sparks Street. They were collected and put into this chest and buried in the clay beneath the normal level of the cemetery. Most of the individuals that were placed in the box were represented solely by portions of skulls, most likely because these elements are easily identifiable as human. Amongst the remains was a particular cranium and mandible (together they are called the skull), which were separated in the box but appeared to belong to the same individual.

The man in the box

The skull belonged to a man, possibly 30 to 45 years old when he died. He had survived a childhood of physiological stress, had healed trauma to his face, periodontal disease, an abscessed tooth, and cavities. His was the only intact skull found during this field season and one of the only complete and unaltered (no warpage, crushing, or structural damage) crania found at the Barrack Hill Cemetery.

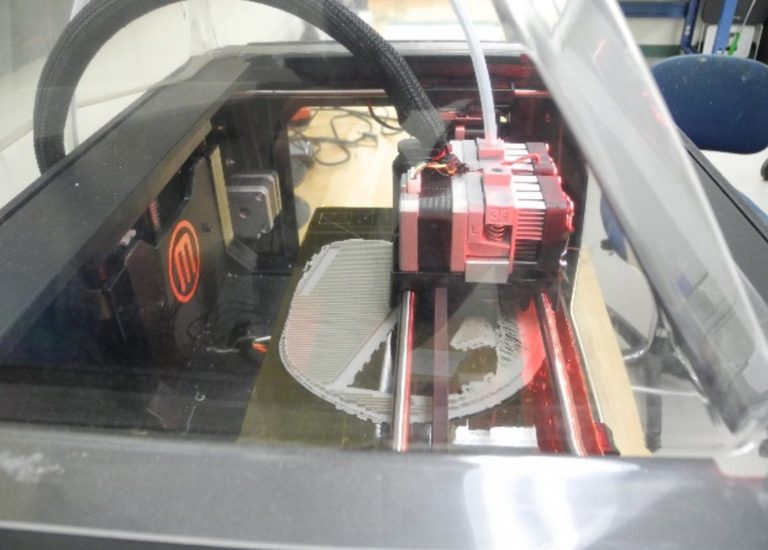

Given the level of preservation, we decided to commission a facial reconstruction of this individual. A forensic artist, Sarah Jaworski, was brought into the project and given the task of putting a face to the Barrack Hill Cemetery project. The first step in the process was to laser scan the man’s cranium and mandible, and then to 3D print them in plastic.

3D printer replicating the skull in plastic.

Given the level of preservation, we decided to commission a facial reconstruction of this individual. A forensic artist, Sarah Jaworski, was brought into the project and given the task of putting a face to the Barrack Hill Cemetery project. The first step in the process was to laser scan the man’s cranium and mandible, and then to 3D print them in plastic.

Forensic facial reconstruction

The cranium and mandible were printed in three segments to avoid any problems during the printing process. When each was complete, Jaworski began preparing the plastic replicas for her work by smoothing out any imperfections and protrusions (by-products of the printing process).

Sarah Jaworski using a Dremel tool to clean any unwanted residual plastic from the model after the 3D printing process.

Facial reconstructions are more than an art — there’s a lot of science that goes into creating the image of someone who lived in the past based on their remains. It requires measurements and population standards for eyes, skin, hair, and morphological features that are not preserved in the skeletal remains.

Front view of the plastic replica with holes drilled for tissue depth markers

Partial plastic 3D print with scientific standards for interpretation

Researching and following published forensic standards allows for the most accurate reconstruction possible. However, it’s through the artist’s hand that these scientific standards can be transformed into a face from the past. In the end, a scientifically based reconstruction of the person was produced.

Three different phases of the facial reconstruction.

Photos provided by Sarah Jaworski.

Three different phases of the facial reconstruction.

The face of the Barrack Hill Cemetery

The forensic reconstruction was completed for the second burial of individuals found at the Barrack Hill Cemetery, which took place on October 6, 2019. It’s currently housed at Beechwood Cemetery, where those recovered from the Barrack Hill Cemetery have been laid to rest in a plot identified for that purpose.

Facial reconstruction produced by forensic artist Sarah Jaworski. Hat provided by the Bytown Museum.

The last reburial

The metal box beneath the excavation zone behind 62 Sparks Street was uncovered in the final hours of a field season that spanned weeks. If the test pit had not been sunk in that particular area, maybe just feet to the left or right, these individuals might not have been found. Call it kismet, providence or luck, I always found the circumstances curious, knowing that the face of this man and the lives of those who were found along with him may never have been revealed if it hadn’t been for that twist of fate.

I’ve been privileged to be part of a team that has been working to tell the stories of these souls lost to time. This week, we invite you to be a part of the story as well. The City of Ottawa and the Beechwood Cemetery are hosting the final reburial of the individuals recovered from the Barrack Hill Cemetery. You’ll be able to see the forensic reconstruction up close and have the opportunity to discuss the stories we’ve presented in this blog series, as well as those still being written. I look forward to meeting you.

Caskets reburied in 2017 at the grave plot named “Barrack Hill Cemetery” at Beechwood Cemetery

Find out more

Read more about the findings in the Barrack Hill Cemetery in the blog series, Bone Detective: Mysteries of Those Found Beneath Downtown Ottawa.

Janet Young

Janet Young specializes in the study of human skeletal remains, and has been working at the Canadian Museum of History since 1994.

Read full bio of Janet Young

Bianca Gendreau

Bianca Gendreau leads an interdisciplinary team of curators working on different approaches to research and enrichment of the national collection.

Read full bio of Bianca Gendreau