Between 1776 and 1840, the non-Indigenous population of British North America increased from under 100,000 to over 1 million. Many newcomers settled in the new colony of Upper Canada, now Ontario. Settlers arriving there found dense forest. The task of clearing and planting the land — and making a home — was daunting.

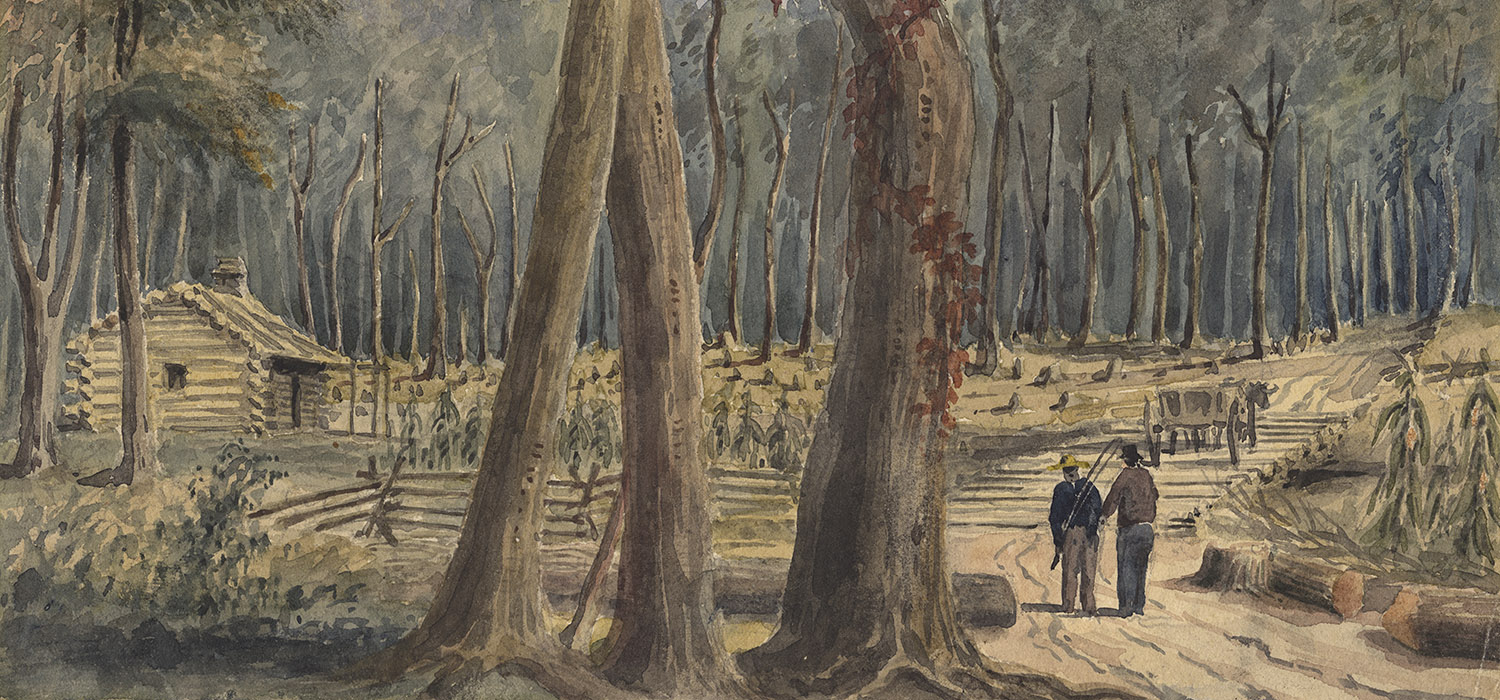

The settler family’s first tasks were to clear some land and build a log house. The land would eventually produce wheat — Upper Canada’s main export — and other produce. In the meantime, the family needed money to survive the first winter. The forest itself filled the gap. Burning hardwoods for potash and taking on seasonal work in the lumber industry provided extra income.

Clearing the Land

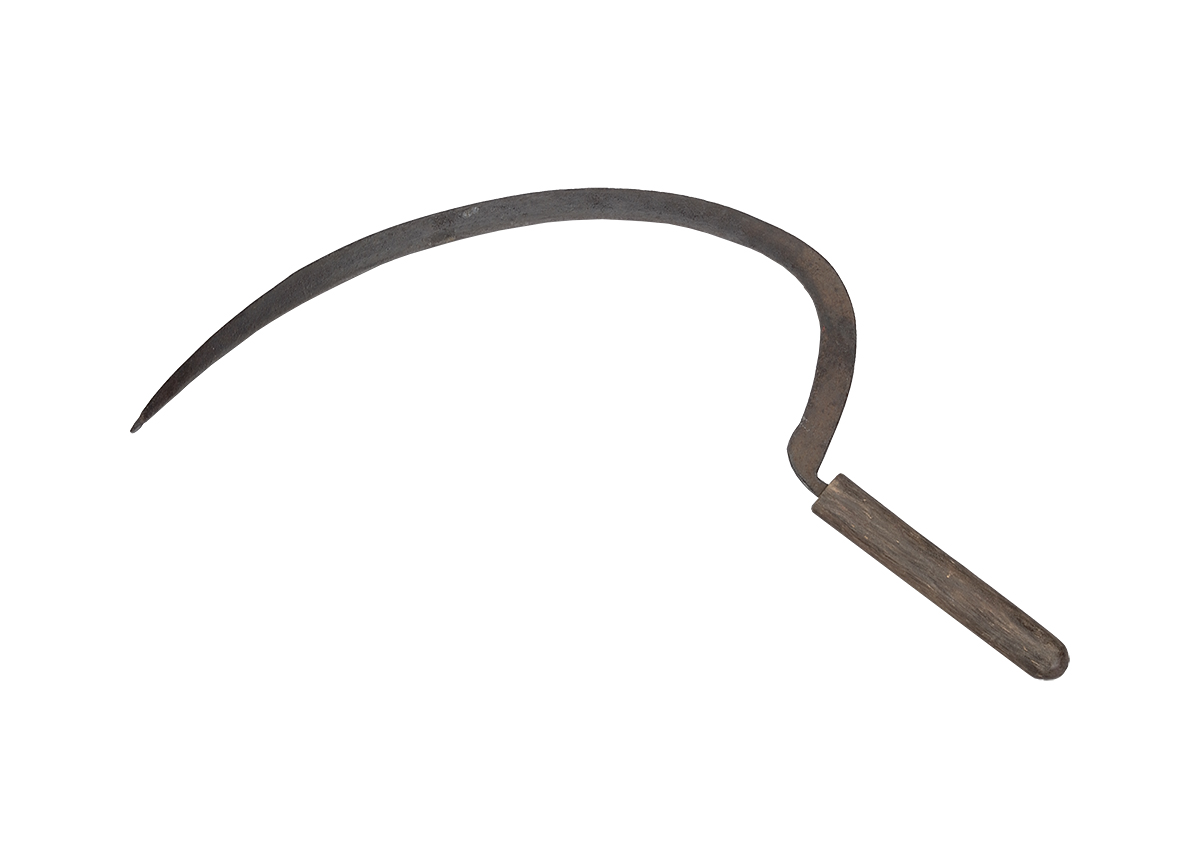

Cutting trees was hard work. Settlers used a felling axe to chop down trees, a broadaxe to square logs, and horses or oxen to move timbers for building. Settlers also burned trees that they did not need for building. The family then boiled the ashes in a kettle to make potash, a soap ingredient, for household use and sale.

It could take years to clear a typical farm lot. Most farmers left some trees standing, for firewood and for maple sugar production.

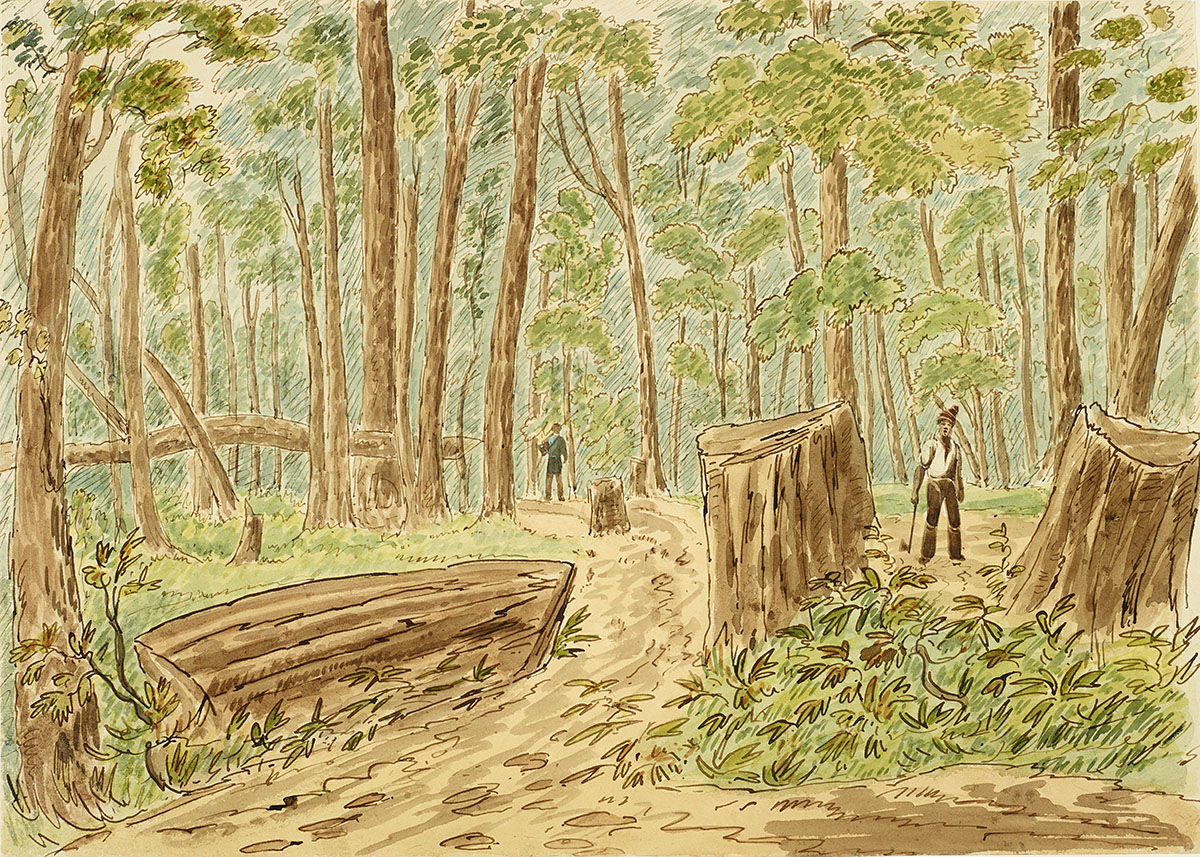

The Lumber Industry

Lumbering and farming went hand-in-hand in Upper Canada. Farmers and their sons might work seasonally as loggers. Lumbering cleared new land for farming. Logging took place in the fall and winter, as it was easier to slide logs over snow and ice than over mud and rock.

When the ice melted, log drivers moved the logs down rivers and lakes to market. Demand for lumber was high, both in the colonies and in Britain.

Clearing the Land

Listen to settler Edward Allen Talbot’s account of homesteading in the 1820s.

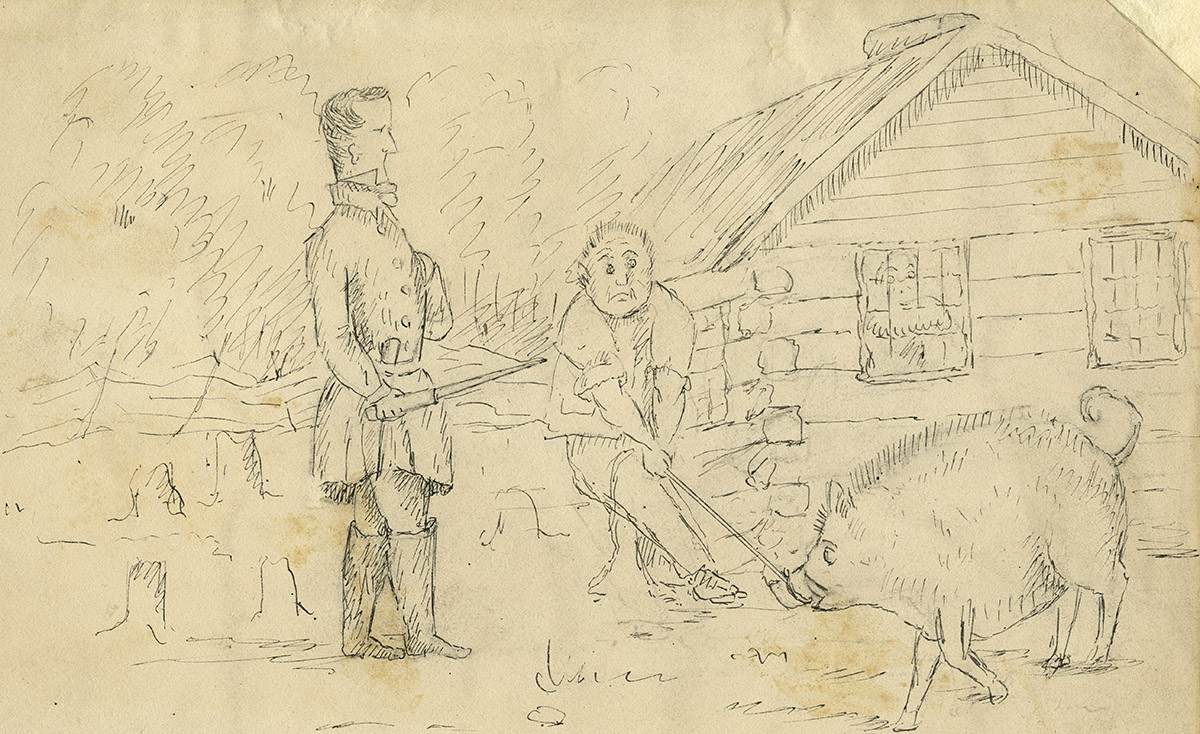

Mixed Farming

Wheat was the main cash crop for Upper Canadian farmers. Farm families also grew fruit and vegetables, and kept livestock, for household use and for sale. Women maintained and processed much of this produce.

Settling Southwold

Southwold, on Lake Erie’s north shore, was a typical Upper Canadian township. Settlers transformed it from a forested, Indigenous homeland into an agricultural, colonial landscape.

In 1790, Indigenous chiefs at Fort Detroit signed a treaty that gave much of southwestern Upper Canada to Britain. Surveyors divided the land, including Southwold, into townships. The government granted part of the township to Colonel Thomas Talbot, who encouraged settlement.

A Map of the Province of Upper Canada

James G. Chewett, 1826

Archives of Ontario, N-5623

The McMullen family farm in Southwold Township, 2016

Southwold Township Communities in Bloom Committee

Special thanks to the McMullen family

Southwold Today

Southwold is still a vibrant community today. Although railways, in the late 1800s, and heavy industry, in the 1900s, have left their mark, the legacy of early settlement is still visible. Agriculture remains the economic mainstay. The township’s main roads, Fingal Line and Highway 3, follow the east and north branches of the old Talbot Road. Descendants of colonial settlers still live in the township and surrounding region, not far from the lands their ancestors cleared and farmed.