In the late 1700s and early 1800s, Indigenous peoples in North America’s northern interior accepted a sustained Euro-Canadian presence in their homelands.

Indigenous peoples provided the knowledge, skills and hospitality that the newcomers needed in order to gain access to furs. In return, Indigenous peoples gained easier access to European trade goods.

In many cases, marriage between Indigenous women and Euro-Canadian traders strengthened this arrangement by forging close family ties.

Euro-Canadian fur traders entered Indigenous homelands on the Prairies from two directions: southwestward from Hudson Bay and northwestward from the St. Lawrence-Great Lakes corridor.

The first group worked for the London-based Hudson’s Bay Company, which wanted to carry its trade inland from its bayside posts in the 1770s. The second group worked for British (mostly Scottish) merchants based in Montréal. In 1779, these merchants formed the North West Company to exploit the fur resources of the Saskatchewan, Churchill and Athabasca river systems.

The Hudson's Bay Company

Coat of Arms, Hudson’s Bay Company

Inscription: Pro Pelle Cutem (a skin for a skin) Hudson’s Bay Company Archives, Archives of Manitoba, HBCA P-237

Hudson's Bay Company Medals

The Hudson’s Bay Company presented these pendants to prominent Indigenous fur suppliers between 1790 and 1821. Such pieces helped the company make and maintain trade alliances.

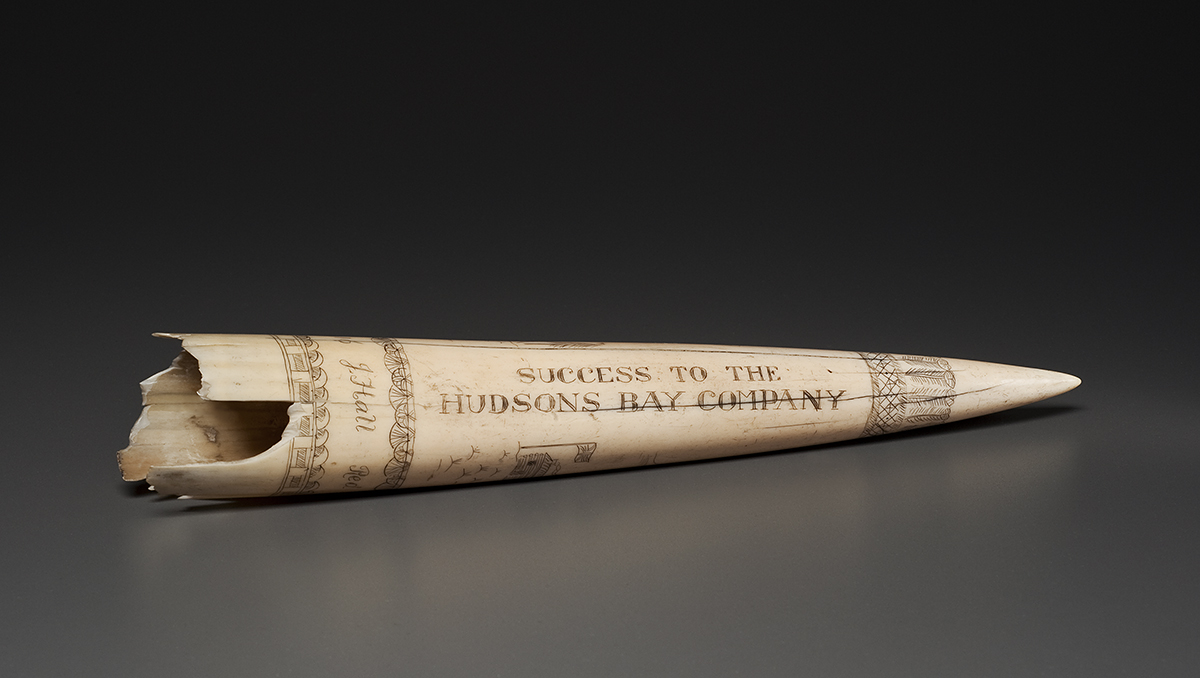

Depicting the Fur Trade

A Hudson’s Bay Company employee engraved this walrus tusk in 1816, at the height of competition between the Hudson’s Bay and the North West companies. The piece reflects the central role that Indigenous peoples had in the fur trade.

Scrimshaw Sculpture, Walrus Ivory

Red River, Manitoba, 1816 CMH, 2008.112.11

Scrimshaw Sculpture, Walrus Ivory

Red River, Manitoba, 1816 CMH, 2008.112.11

Matonabbee and Ackomokki

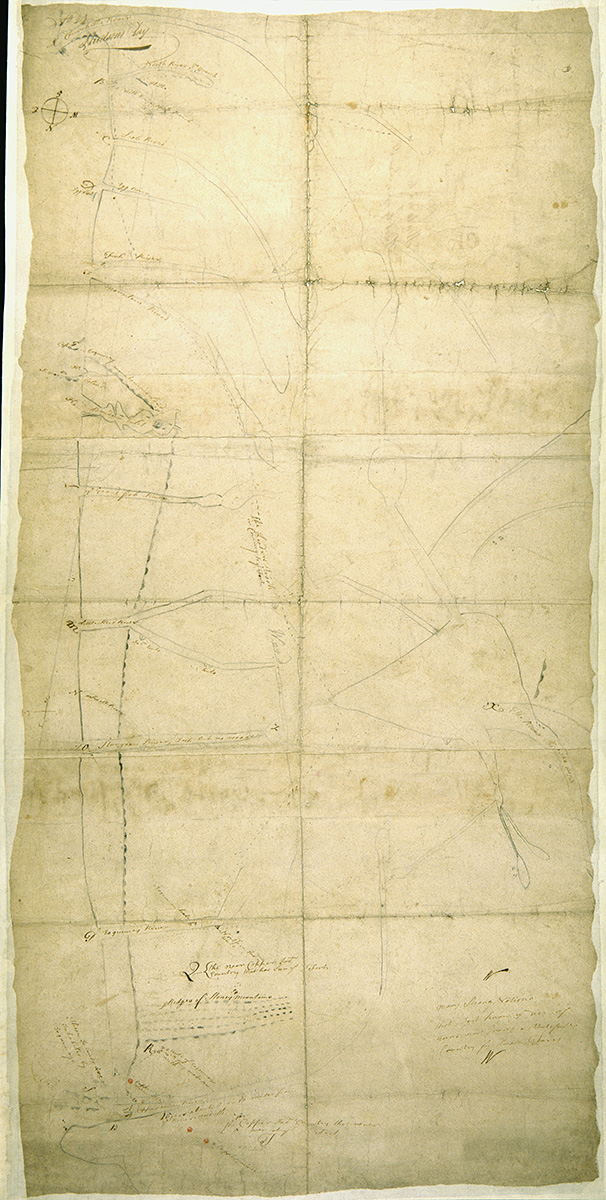

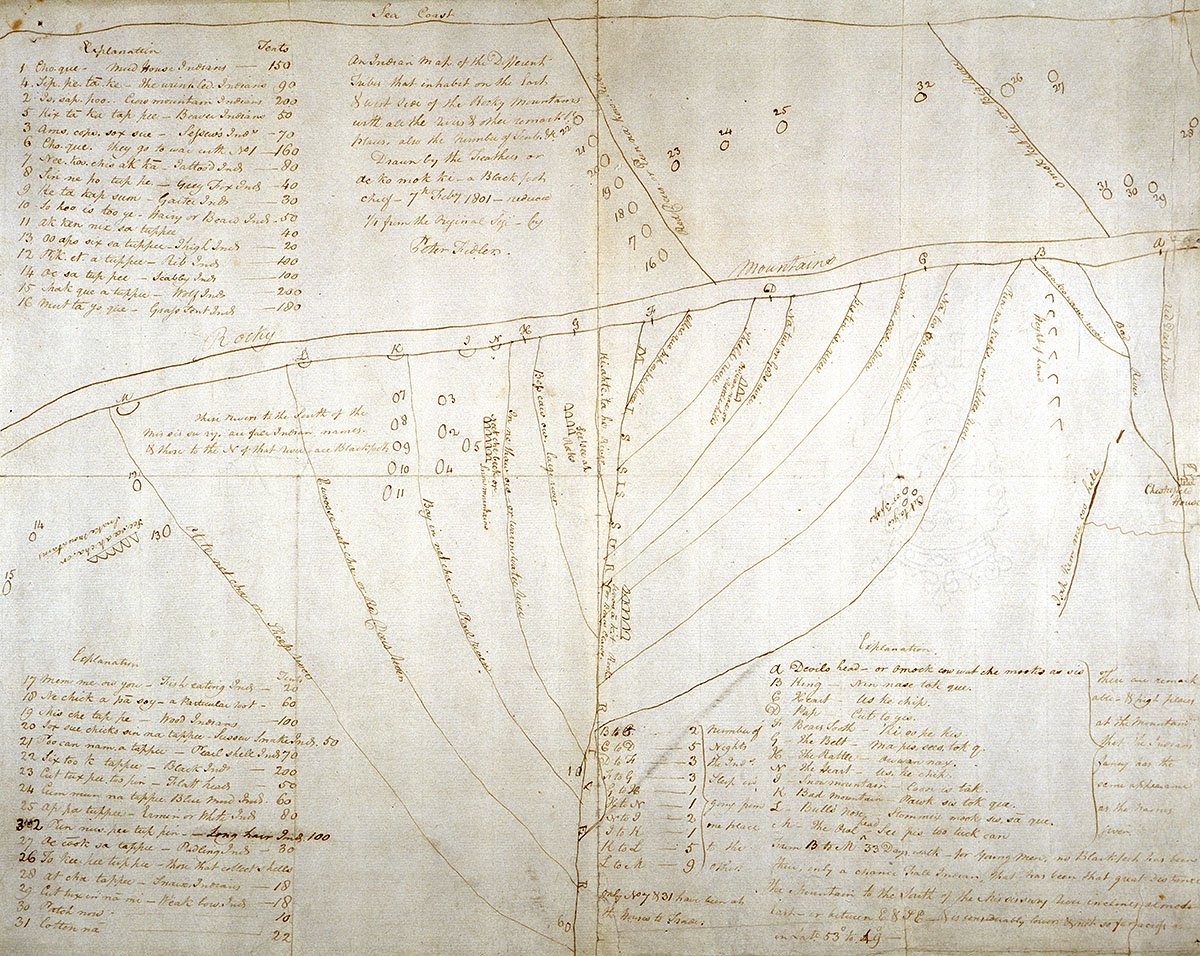

By sharing knowledge of their homelands, Indigenous peoples allowed the Hudson’s Bay Company to extend its trade inland. Denésoliné leader Matonabbee guided trader Samuel Hearne to the Coppermine River in 1770–1771, after drawing a detailed map of the route for the company. In 1801, a Siksiká (Blackfoot) chief named Ackomokki drew a map for trader Peter Fidler. Covering a vast area on either side of the Rocky Mountains, the map identified the region’s rivers, trails and First Nations.

The Most Friendly Hospitality

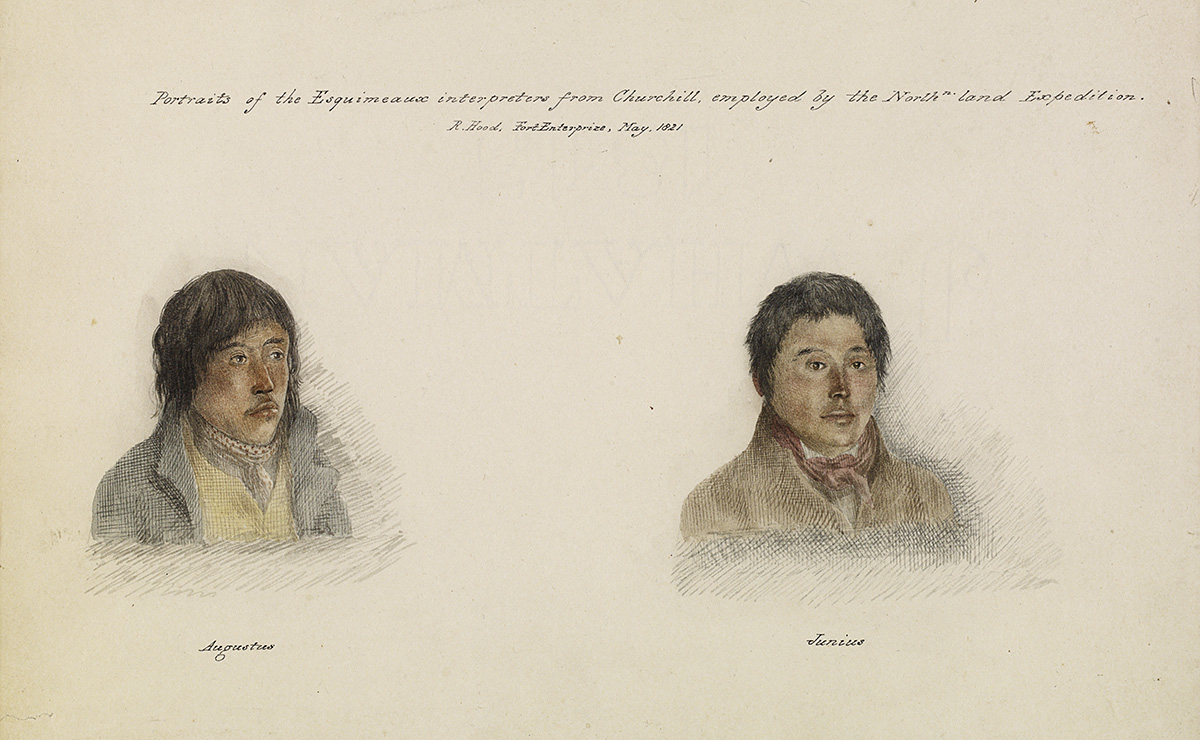

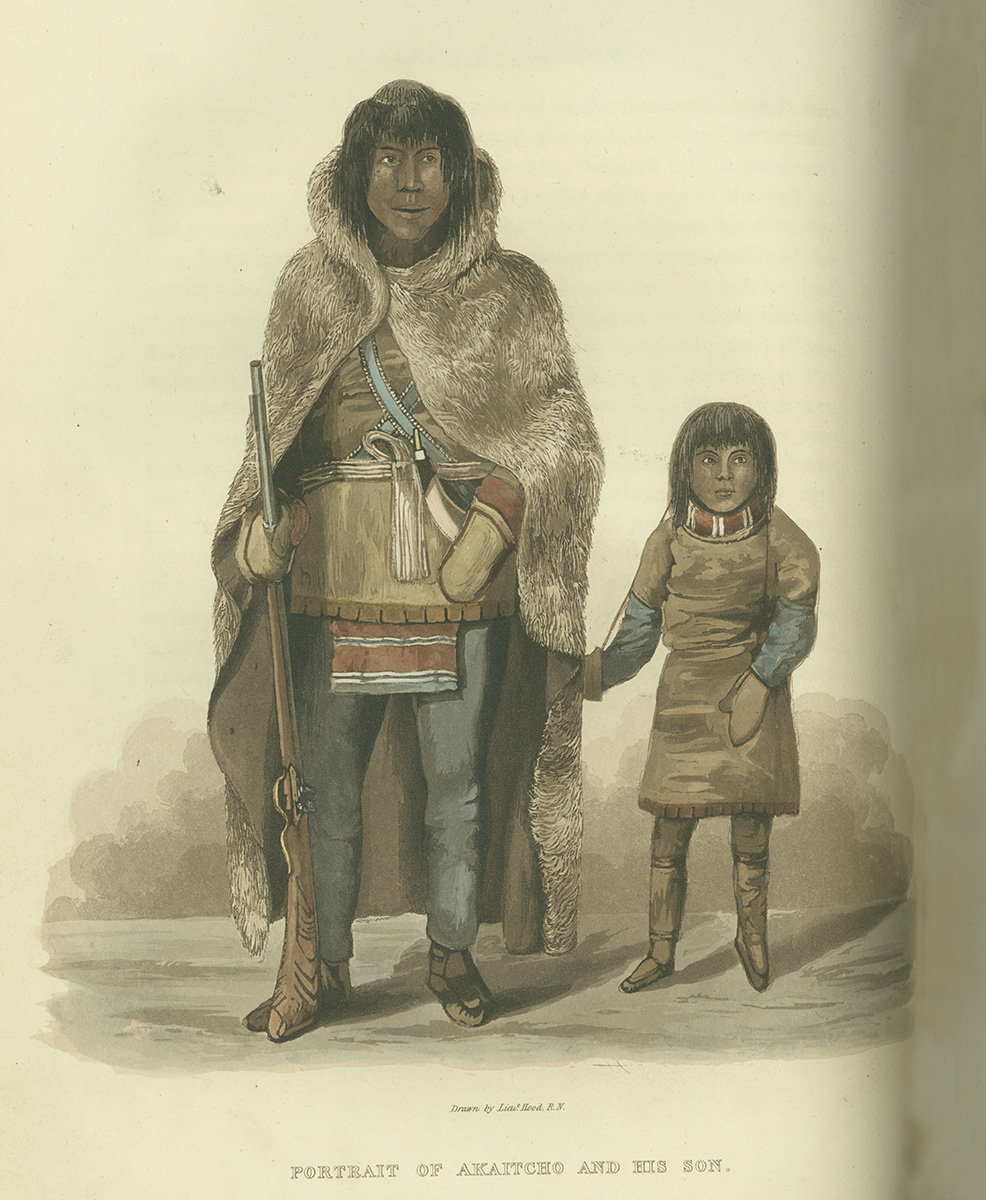

Indigenous guides were vital to British Navy Lieutenant John Franklin on his 1819–1822 search for the Northwest Passage. His expedition relied on two Inuit interpreters: Tatannuaq, also known as Augustus, and Hiutiruq, also known as Junius. In 1821, Dené chief Akaitcho and his band saved the Franklin expedition from starvation. Franklin later wrote: “Akaitcho shewed [showed] us the most friendly hospitality, and all sorts of personal attention, even to cooking for us with his own hands.”

Portraits of Indigenous guides

Robert Hood, an officer in Lieutenant John Franklin’s expedition, sketched portraits of Tatannuaq, Hiutiruq, Akaitcho and his son. Hood died during the expedition, but Franklin preserved his drawings and journal.

Portraits of Tatannuaq and Hiutiruq

Inscription: Portraits of the Esquimeaux interpreters from Churchill, employed by the North[er]n Land Expedition. R. Hood, Fort Enterprize, May 1821 Augustus Junius Robert Hood, May 1821 Library and Archives Canada, R13133-438

Portrait of Akaitcho and his son

Edward Francis Finden, after Robert Hood From John Franklin, Narrative of a journey to the shores of the polar sea, 1823 CMH, RARE G 650 1819 F825 1823

The North West Company

Preliminary design for a coat of arms, North West Company

Inscription: Perseverance About 1800 to 1820 Library and Archives Canada, C-008711

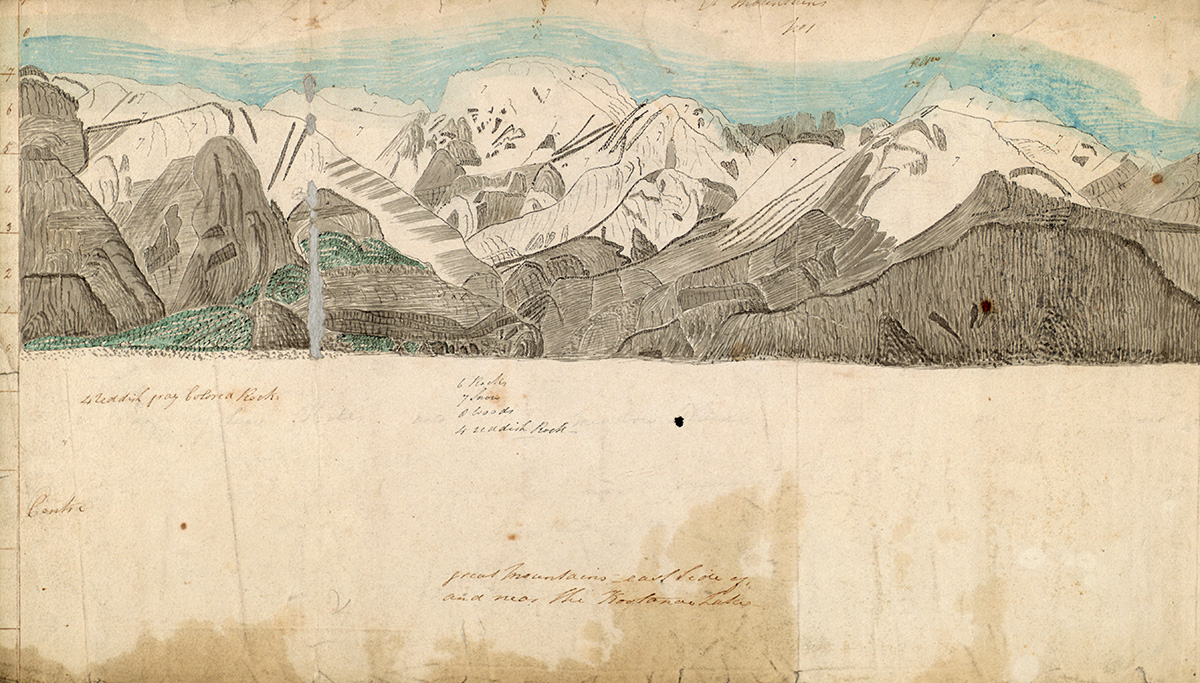

A Great Advantage

Between 1792 and 1814, trader and surveyor David Thompson produced maps and drawings of western plains, mountains, lakes and rivers. He travelled the country in the company of his wife, Charlotte Small. Born to a Sakāwithiniwak (Woodland Cree) mother and a Scottish father, Small served as interpreter between her husband and Indigenous people. Thompson wrote of her: “My lovely Wife is of the blood of these people, speaking their language, and well educated in the [E]nglish language; which gives me a great advantage.”

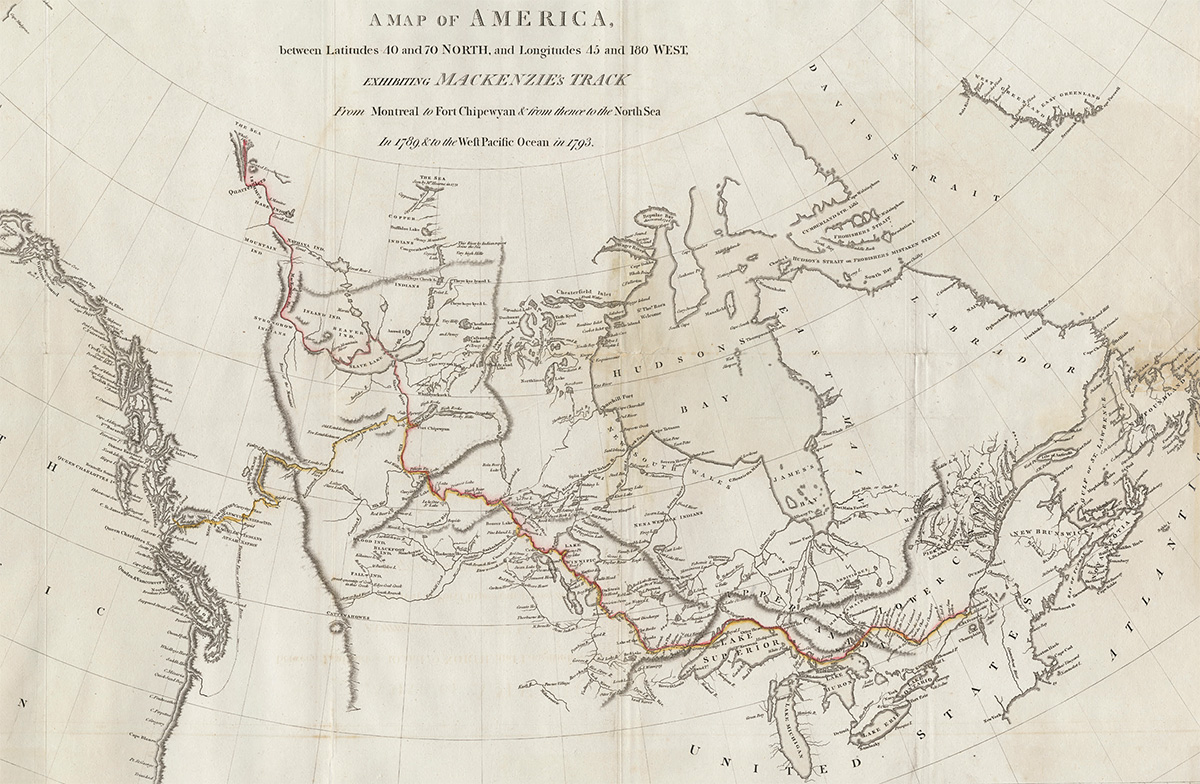

From Canada by land

North West Company trader Alexander Mackenzie became famous for travelling the Mackenzie River to the Arctic coast in 1789 and for reaching the Pacific Coast overland in 1793. Yet these achievements would not have been possible without support from Indigenous guides. Mackenzie’s guides teased him about his dependence on their knowledge of the country. One of them asked, ironically, “Do not you white men know everything in the world?”

Portrait of Sir Alexander Mackenzie

Thomas Lawrence, about 1800 National Gallery of Canada, 8000

Map of Alexander Mackenzie’s voyages to the Arctic and Pacific coasts

From Alexander Mackenzie, Voyages from Montreal, 1801 CMH, Library, RARE FC 72 M33 180