On the Northern Plains, First Peoples developed a unique way of life centred on hunting bison herds.

Climate change, after deglaciation and the extinction of large animals like the mammoth, resulted in the rise of vast herds of bison on the Northern Plains.

Northern Plains Cultural Area

About 10,000 years ago, First Peoples began to develop techniques to hunt bison herds communally. They established a powerful spiritual relationship with the bison. That relationship persists to this day.

Jumps — places where First Peoples could drive entire herds over cliffs — were the most productive way to hunt bison. In southern Alberta, hunters used Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump for over 6,000 years, until the 1800s. Over time, hundreds of thousands of bison bones left at the bottom of the cliff formed a deposit 12 metres deep. The bone bed reveals a remarkably ancient and stable way of life.

Bison Skull

First Peoples on the Northern Plains consider bison skulls to be sacred. They sometimes use them in ceremonies, such as the Sun Dance, to ensure healthy herds and successful hunts.

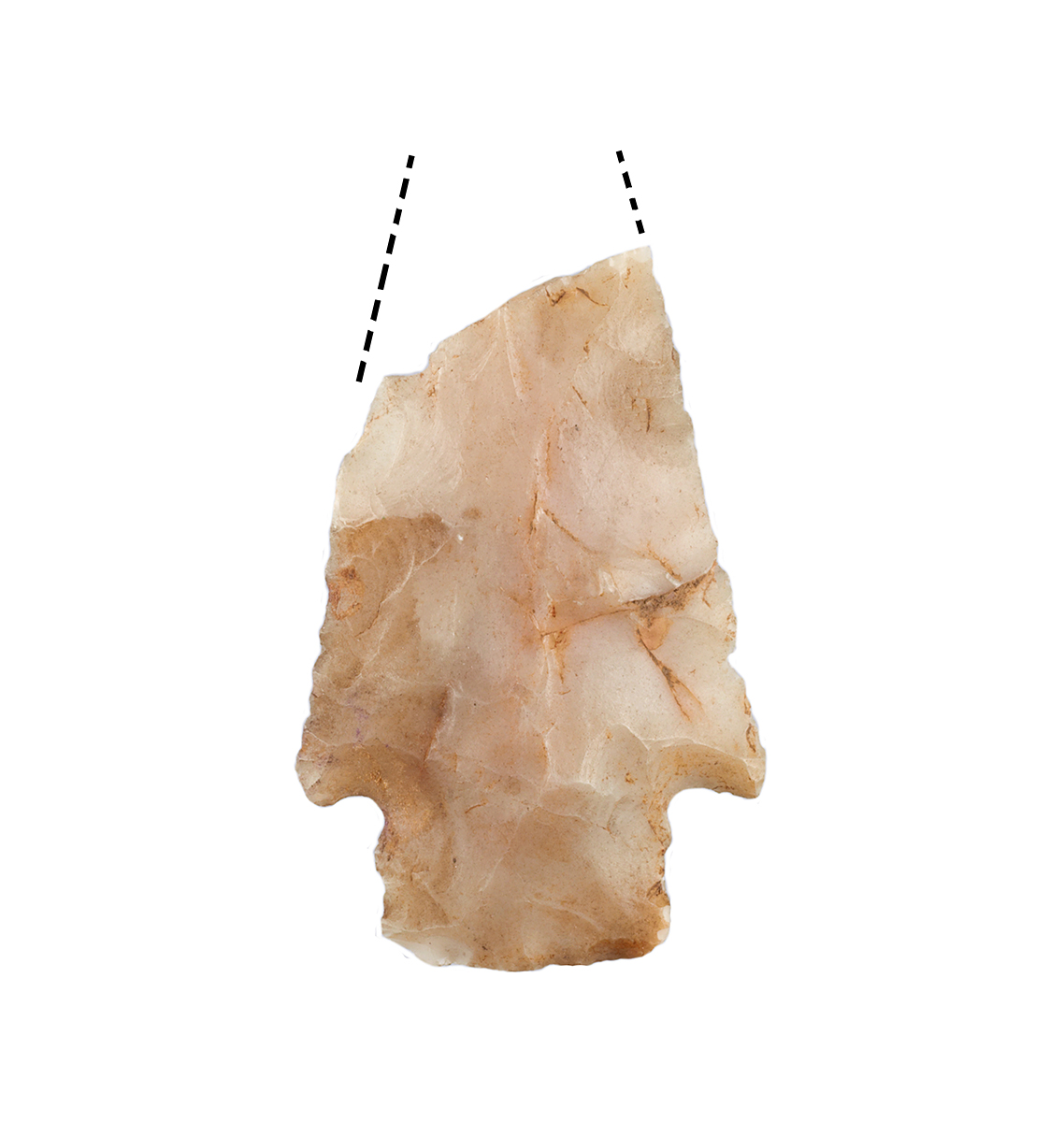

Projectile Point, stone (Chalcedony)

8,500 years ago CMH, X-A:2920

Spear Points

First Peoples hunted individual bison with hand-held spears tipped with stone points. Spear point styles evolved over time, reflecting changing technology. The points became smaller as hunters adopted lighter throwing spears that could be propelled long distances.

Operating Head-Smashed-In

A natural basin and an 8 kilometre network of over 500 stone cairns helped to funnel bison towards a 20 metre sandstone cliff. The Piikani named this cliff pis’kun, or the Buffalo Jump. Exceptionally skilled hunters, called buffalo runners, disguised themselves as bison and wolves to lure the herd into position. At a given signal, the runners and other hunters stampeded the herd over the cliff. At the bottom, people killed any bison that had survived the fall.

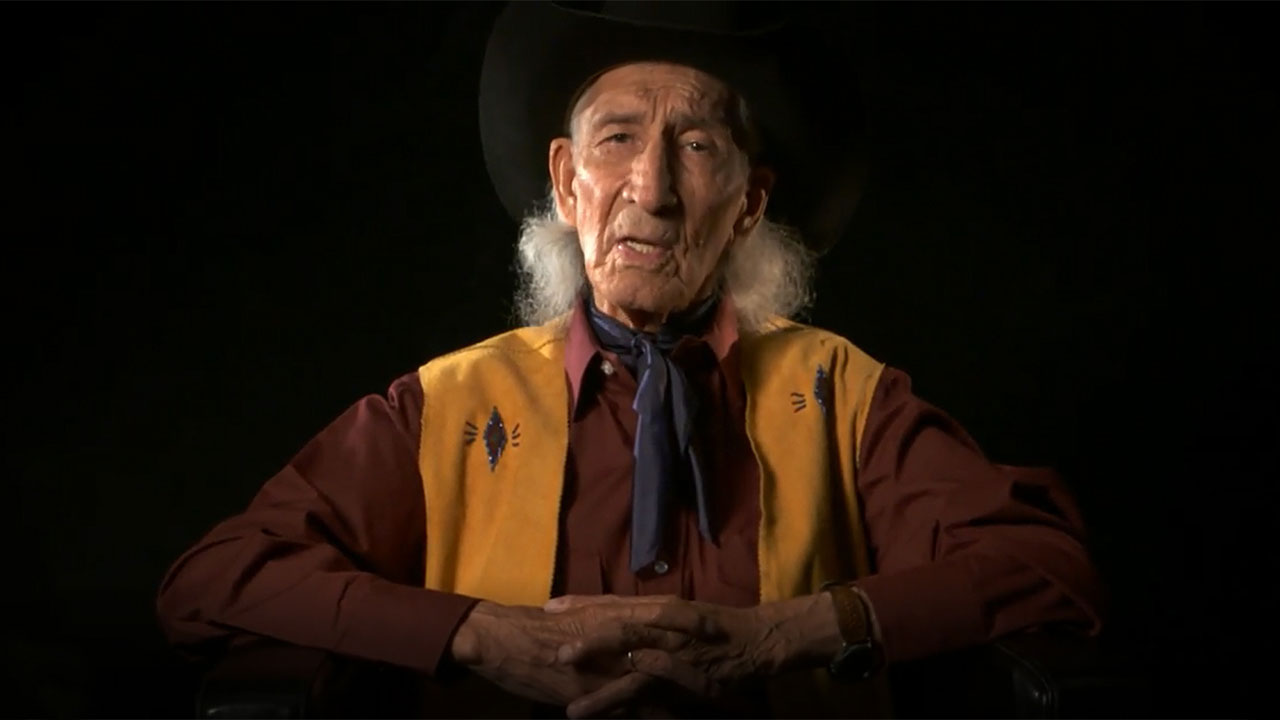

Modern Voices: Elder Wilfred Yellow Wings

Watch Elder Wilfred Yellow Wings of the Piikani First Nation describe the enduring relationship between the Piikani, bison and buffalo jumps.

End-scraper, stone (Knife River Flint)

5,000 to 2,500 years ago CMH, X-B:367

A Community at Work

After the bison hunt, communities worked together for days to process hundreds of bison before the meat spoiled. They used almost all of the bison. Hides were tanned for blankets and clothing, meat dried and stored, bones boiled to extract grease, tools made from bone, and sinew removed for thread. This cooperative work became a cherished community event filled with feasting, celebration and family.

Making Pemmican

First Peoples used stone hammers to pound dry meat into a powder, mixing it with fat and sometimes berries to make pemmican.

Hammer, stone

1,000 years ago. CMH, FgNe-6:156

Hammer, stone and hide

150 years ago. CMH, V-B-417

An Enduring Relationship

The relationship between bison and First Peoples has been evolving since earliest times. More than just a critical economic staple, bison featured prominently in the spiritual beliefs of First Peoples throughout the Northern Plains.

The jumps where communities hunted and processed bison are revered cultural and historic places. Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump Interpretive Centre, in southern Alberta, is a UNESCO World Heritage site.

Bison vertebra with lead musket ball

200 to 150 years ago CMH, X-B:16a-b

New Technologies, Old Techniques

Metal arrowheads and firearms quickly replaced stone tools on the Northern Plains after the arrival of Europeans. However, bison jumps like Head-Smashed-In were so effective that they continued to be used well into the 1800s, long after the arrival of horses and guns.

Calling the Bison

Bison are powerful creatures. Before they could be hunted, First Peoples needed to make spiritual preparations. Bison-shaped fossils, known to the Piikani as iniskim, or buffalo stones, were used in special ceremonies to attract bison. Archaeologists have found iniskim on sites that are thousands of years old. The Piikani still use iniskim in ceremonies.