As Canadians face another winter of COVID-19, vaccine mandates — the proof often required to work, shop or participate in various other activities — have become a hot topic. Following a surge in vaccination during the spring and summer of 2021, as vaccines became available to most adult Canadians, vaccinations across the country have slowed. Today, many health agencies are more focused on reaching those who may be hesitant about the COVID-19 vaccine, in an effort to fully vaccinate a sufficient majority of eligible Canadians to achieve community immunity.

Smallpox and early vaccination campaigns

Vaccine mandates and the surrounding debates are nothing new, in Canada or around the world. It took decades for the first smallpox vaccines to gain acceptance and widespread use during the 19th century, despite several efforts to make the vaccine mandatory.

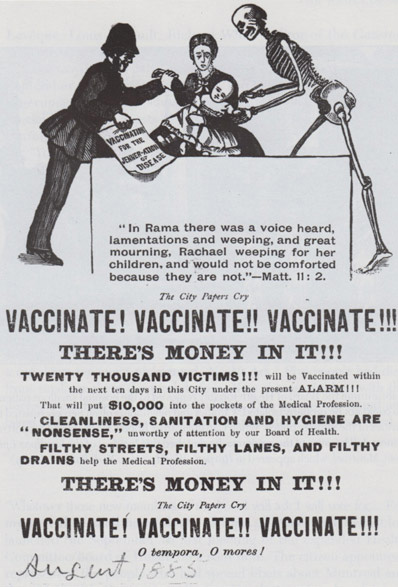

Canada’s most notable early vaccine policy crisis occurred during an 1885 smallpox outbreak that hit Montréal particularly hard. Anti-vaccination groups mobilized to protest mandatory vaccine measures, leading to public violence across the city. Other groups protested mandatory vaccinations for children in Toronto schools at the turn of the 20th century.

Anti-vaccination poster, 1885

Source: Michael Bliss, Plague: How Smallpox Devastated Montreal (Toronto: HarperCollins, 1991)

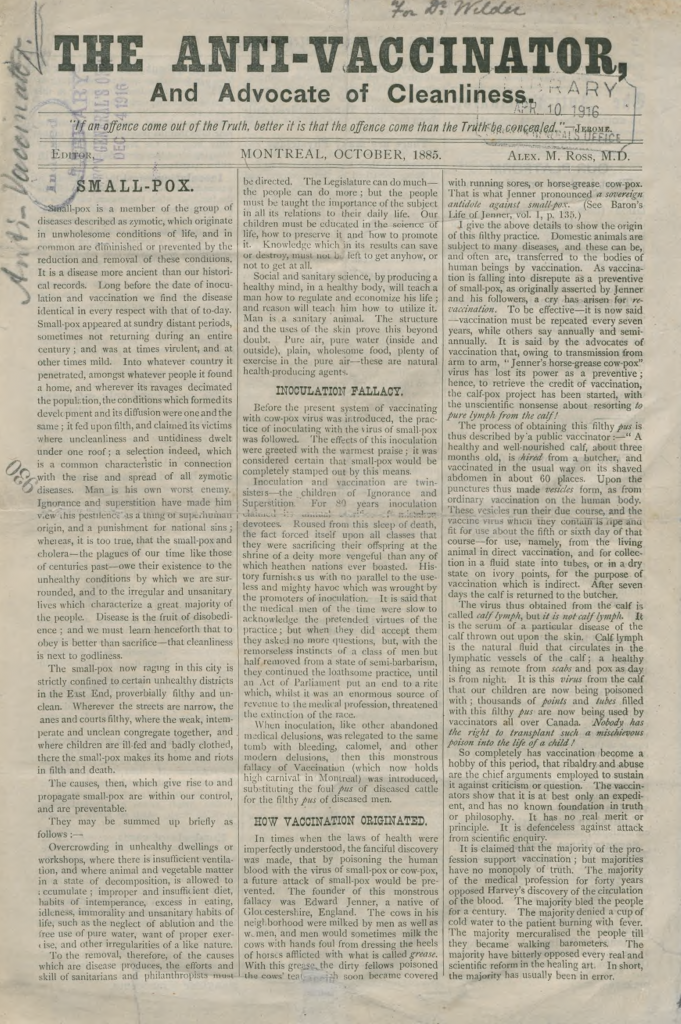

The Anti-Vaccinator, published by Alexander Ross, Montreal, 1885

Anti-vaccine campaigns would continue into the 1920s, as historian Forrest Pass has noted in writing about a smallpox outbreak in the 1920s.

Proof of vaccination required

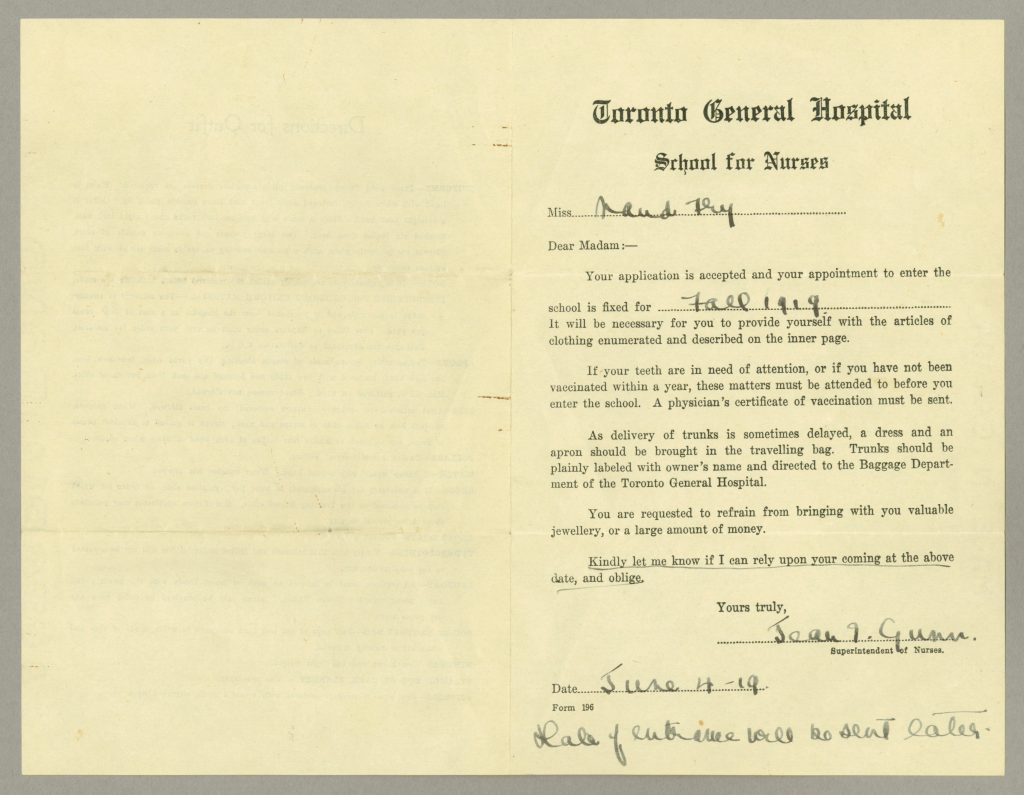

By the early 20th century, however, mandatory vaccination was becoming more commonplace, particularly within healthcare settings. The Toronto General Hospital School for Nurses, for instance, required all admitted students to submit proof of vaccination before starting their programs.

Admission letter from the Toronto General Hospital School for Nurses to Maud Fry, June 4, 1919, CMH 2004-H0037.34. IMG2008-0067-0032-Dm

This admission letter to Maud Fry noted some key entry requirements: “Your application is accepted and your appointment to enter the school is fixed for Fall 1919. It will be necessary for you to provide yourself with the articles of clothing enumerated and described on the inner page. If your teeth are in need of attention, or if you have not been vaccinated within a year, these matters must be attended to before you enter the school. A physician’s certificate of vaccination must be sent.”

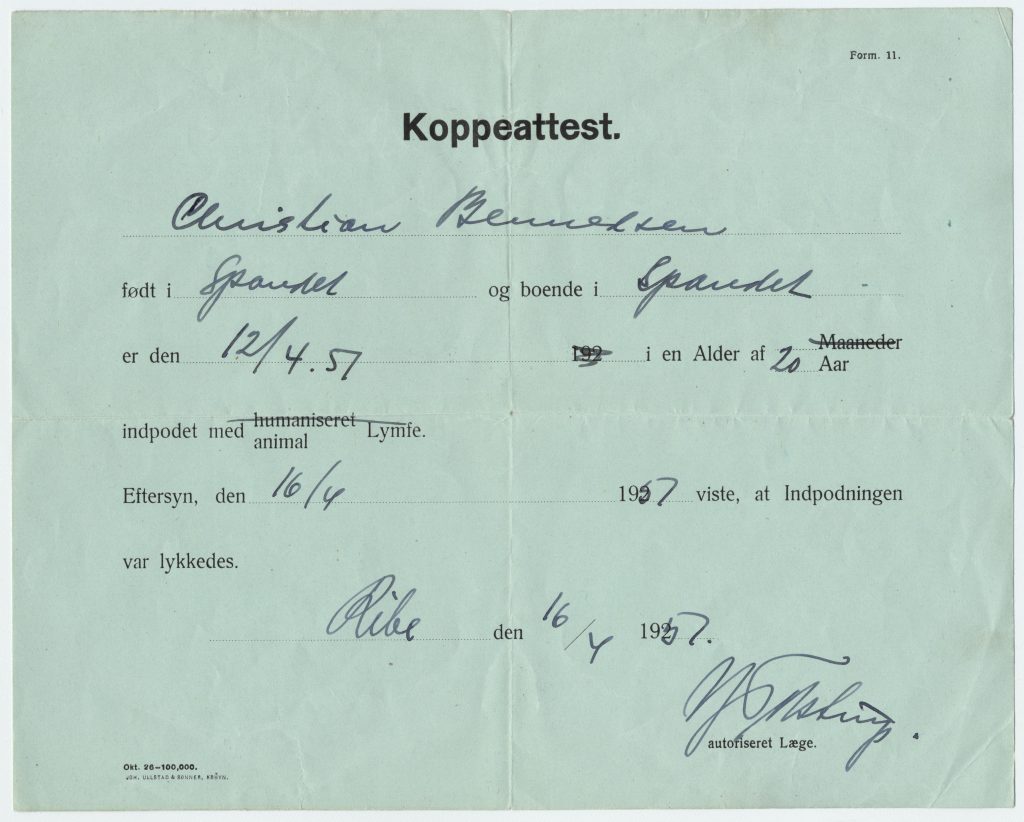

Immigration was another key focus for vaccine requirements throughout the 20th century.

This “Koppeattest,” or smallpox immunization certificate, was issued in Ribe, Denmark, for Christian Bennedsen. Bennedsen emigrated to Canada as a farm labourer in 1951, but later moved to Toronto, married, and in 1959 became a Canadian citizen. This document is part of his immigration papers. CMH P45-2.2.

Combatting childhood diseases

The development of an array of vaccines against diseases such as diphtheria, polio, mumps and measles significantly lowered death rates associated with these diseases. Vaccination education and awareness campaigns by public health agencies — combined with mandatory vaccination policies for trade schools, immigration and other arenas — were essential to ensuring high vaccination rates.

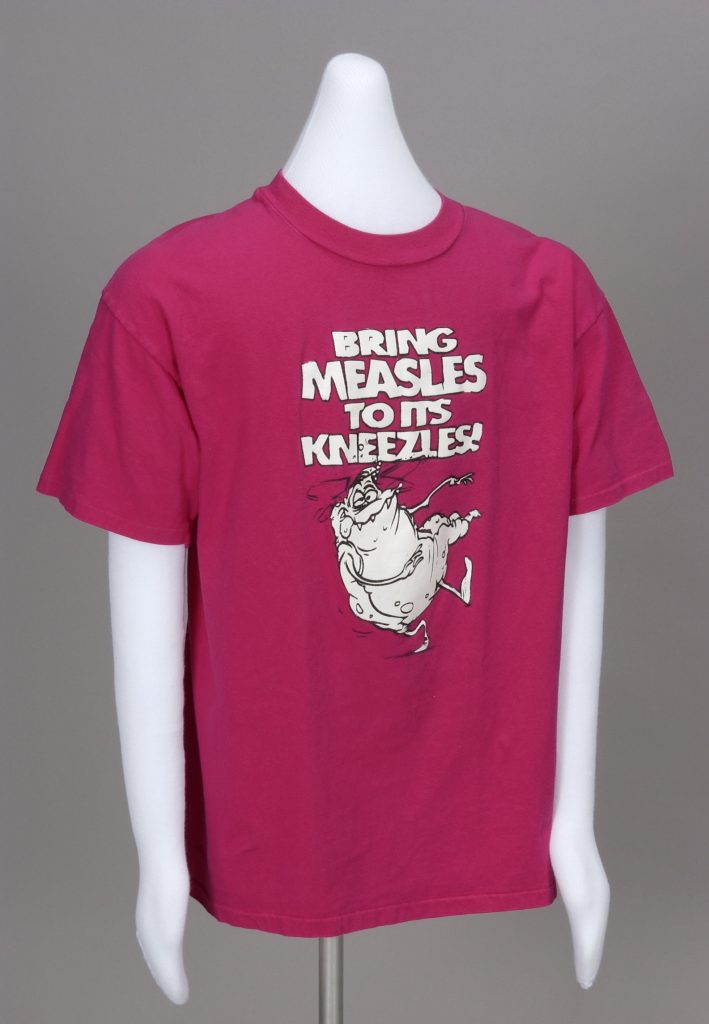

Bringing measles to its knees

In the late 1970s, a spike in measles cases pushed many Canadian provinces to enact mandatory vaccination policies in public schools. Many of these remain in place today, and many Ontarians still have yellow immunization cards — the administrative legacy of these policies.

Medical understanding of the efficacy of the measles vaccine also led to the adoption of a two-dose vaccination policy in the 1990s. Canadian and provincial health agencies, along with health authorities around the world, combined public education with changes to childhood vaccination requirements, significantly reducing measles outbreaks through a mass immunization effort.

The T-shirt below was a somewhat whimsical part of British Columbia’s 1996 public education campaign about the need for a second dose of the measles vaccine. From April through June 1996, about 700,000 of the province’s 900,000 children, ages 18 months to 18 years, were vaccinated.

T-shirt from the Canadian Nursing History Collection, CMH 2004.90.1

The road ahead

Vaccine mandates, and the debates surrounding them, are nothing new. Public health officials have frequently combined compulsory vaccination policies with broader public education in an effort to immunize as many people as possible. Today’s vaccination debates and awareness campaigns may use different methods, such as social media, but the issues and concerns of earlier years often remain.

Preserving history

Tell us what you think: What types of objects or documents do you think would best capture this latest chapter in the history of public health in Canada?

Further reading

- Katherine Arnup, “‘Victims of Vaccination?’: Opposition to Compulsory Immunization in Ontario, 1900-90,” Canadian Bulletin of Medical History 9 (1992), pp. 159–176.

- Paul Adolphus Bator, “The Health Reformers versus the Common Canadian: The Controversy over Compulsory Vaccination Against Smallpox in Toronto and Ontario, 1900–1920,” Ontario History 75, 4 (1983), pp. 348–373.

- Michael Bliss, Plague: How Smallpox Devastated Montreal (Toronto: Harper Collins, 1991).

- Catherine Carstairs, Bethany Philpott and Sara Wilmshurst, Be Wise! Be Healthy! Morality and Citizenship in Canadian Public Health Campaigns (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2018).

- Magda Fahrni and Esyllt Jones, Epidemic Encounters: Influenza, Society, and Culture in Canada, 1918–20 (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2013).

- Esyllt Jones, Influenza 1918: Death, Disease, and Struggle in Winnipeg (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2007).

- Forrest Pass, “An ‘Epidemic’ of Fake News a Century Ago,” Library and Archives Canada Discover Blog.